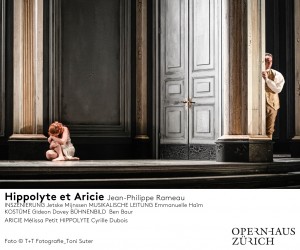

Switzerland Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie: Soloists and Chorus of the Opernhaus Zürich, Orchestra La Scintilla / Emmanuelle Haïm (conductor), Opernhaus Zürich, Zurich, 19 & 22.5.2019. (CCr)

Switzerland Rameau, Hippolyte et Aricie: Soloists and Chorus of the Opernhaus Zürich, Orchestra La Scintilla / Emmanuelle Haïm (conductor), Opernhaus Zürich, Zurich, 19 & 22.5.2019. (CCr)

Production:

Director – Jetske Mijnssen

Set designer – Ben Baur

Costumes – Gideon Davey

Lighting – Franck Evin

Choreography – Kinsun Chan

Chorus director – Janko Kastelic

Dramaturgy – Kathrin Brunner

Cast:

Aricie – Mélissa Petit

Hippolyte – Cyrille Dubois

Phèdre – Stéphanie d’Oustrac

Thésée – Edwin Crossley-Mercer

Neptune, Pluto – Wenwei Zhang

Diana – Hamida Kristoffersen

Œnone – Aurélia Legay

Three Parques – Nicholas Scott, Spencer Lang, Alexander Kiechle

Diana’s priestess, hunter – Gemma Ní Bhriain

Hunter – Piotr Lempa

The season near its close, the Opernhaus Zürich has proffered quite a streak of great music and great shows of late: a month ago it premiered a strong production of Rossini, then pulled off a sumptuous Bellini in concert form some weeks ago, before trying its hand now at the first opera of French Baroque composer Jean-Philippe Rameau, whose works almost never appear on Swiss stages (it took 170 years to get this one over the border from France all the way to … Geneva). And they are not through yet: there’s still a Nabucco to premiere, with Fabio Luisi conducting and Michael Volle eponymous.

It is almost embarrassing, the riches. Of the new productions here this season, Manon and Hansel und Gretel were theatrical duds, Sweeney Todd and Die Gezeichneten were musically mixed, and the rest have been terrific. Bringing French Baroque opera into the mix shows the versatility of this company, its two orchestras, and of its public, for that matter. A recent Médée here set the stage for le maître Rameau, and though the two performances of Hippolyte et Aricie I attended weren’t sold out, the audience’s hearty embrace of the musicians was a testament to a warm and open bond.

‘What we hear seems more graceful, finer, more fleeting, as if painted improvisationally; what we see is akin to a bright mosaic, rich in variety and jarring in its musical and scenic excursiveness.’ So wrote German critic Uwe Schweikert in an essay on Rameau, highlighting the foreign language of this music when compared to Italian melodic idiom so dominant in Europe (then as now). If you don’t know Rameau, or if you had him down for a prissier Bach, then listen to the ‘Trio des Parques’ in the second act of this opera. You’ll think Orfeo ed Euridice lacked inspiration by comparison, the way Gluck’s Furies bark unisono at Orpheus; Rameau marches his Fates enharmonically towards diminished fifths, and your throat starts to tighten as the trio swirls around its victim. It is the scene in which the Fates (Parques) tell Thésée that no, he doesn’t get to kill himself, and that if he thinks Hades is bad, just wait until he gets back home and sees his living room (‘Tremble, Frémis d’effroi! Tu quittes l’infernal empire pour trouver les enfers chez toi’). Rameau’s librettist Pellegrin had Sartre beat by two hundred years: Hell really is other people.

Jetske Mijnssen, whose production this is, mostly emphasises the trope of the bourgeois family drama and its concomitant miseries in her storytelling. Happily, the magic of the music forces her hand to operate on many levels at once, keeping all the panniers and bodices from constricting the show’s energy. Hippolyte loves Aricie, but his stepmother Phèdre keeps getting in the way, fobbing Aricie off to the cult of Diana; this is Racine’s story of Phèdre’s desire for her stepson, his immediate rejection, and her hara-kiri lest the shame of her desire see the light of day. Then there’s Phèdre’s consort, Thésée, who is led to kill his own son (and doesn’t outsource it to monster as in the original) when it isn’t clear whether Hippolyte was violating Phèdre or the other way around. Neptune and Diana are less gods than grandparents, austere and correct.

Mijnssen isn’t satisfied, and imposes another layer. Rameau’s second act consists of a scene from classical mythology that Racine had not included; composer and librettist sent Thésée down the River Styx to rescue his faithful companion in battle, Perithous (here an invented dancing role, with compelling moves from dancer Davidson Hegglin Farias). Mijnssen said that when she heard the music of Thésée seeking Perithous in the underworld, she heard love. She runs with the idea, and while it works eventually, there is the gallous opening scene of Phèdre sicking the three Fates on Perithous because of his bad manners at the dinner table (the epicentre of all bourgeois terrors) – Perithous sits on King Thésée’s lap for a campy caress. I am with Phèdre on this one: not before dessert, people.

It is the other levels that are the most winning: the fantastical one, the crows of hell picking apart Perithous’s visible innards, Pluto hoarding his carrion. Or the Christian level, as Diana’s cult forces Aricie onto her knees in marriage at a prie-dieu, and the robed, clerical Parques officiate. Or the simple love between Hippolyte and Aricie, and even of Thésée as he embraces his disgraced Phèdre sweetly as she dies. Mijnssen’s real coup is her use of Rameau’s divertissements between acts to keep the story flowing tautly. An example of such an interlude handled brilliantly: A potentially dopey sailor’s song to Neptune about the heart’s being like a sailor – the heart braves tormenting storms instead of staying safely at port – is turned here into a play-within-a-play in which Thésée is made to watch, Hamlet-like, a pageant of his family’s turmoil.

Better still: Ben Baur is one of the best operatic set designers around, and he and Mijnssen do a whole lot with a little. This is the third stage of Baur’s I have seen, and although I am not sure he will ever beat his brilliant slide-rule of laterally moving rooms in a 2015 production of Vivaldi’s Verità in cimento, this one is a winner. The tholos colonnade he props on the single-set revolve stage here is the production’s central trick in making this opera, likely a nightmare to stage, seem so exciting, once the actual plot kicks in. The temple is always shifting at a slow clip, a twirling walk of the plank for the doomed characters. An imposing door divides realms and lovers; a full rotation reveals a scene change, from Hades to the royal parlour to Diana’s creepy temple. Franck Evin, whose lighting work here is as strong as always, gives Diana lavish pastels, then Hades a bilious green, then Hippolyte blinding gold for his coronation. Evin, Mijnssen and Baur’s success was aided by a contribution from conductor Emmanuelle Haïm: a scholar of Rameau, she personally curated this particular palimpsest of Hippolyte et Aricie‘s score from the five extant original versions. What emerges is smart theatre that is not so vain as to supersede Rameau’s music.

It is hard to imagine an opera performance being better blended. Particularly on opening night (slightly less so for the second performance I saw), orchestra and soloists and chorus sang with such harmony of scale that it was more like a remastered film than live theatre. Man, those Parques! Haïm was conducting the Orchestra La Scintilla for the first time, and could have gone a bit louder or had the strings dig in to a brushier, martele grind at times. But taken together, both the general sense of flow and the great thrill of Rameau’s abrupt harmonic shifts were the result of Haïm’s expert hand. La Scintilla’s four baroque flutes sound phenomenally good.

Singing-wise, Zurich again is able to attract top talent for this repertoire. Opening night showed the coquettish, hateful prowess of Stéphanie d’Oustrac as Phèdre, her voice lush and pointed as she plotted then scorned, capable of much tenderness amidst the wrath. Baritone Edwin Crossley-Mercer is another powerful singer; his Thésée had the gravitas of a king and the sensitive resonance of the penitent. By the second performance, the subtlety of Mélissa Petit as Aricie became apparent as an asset: the top of her voice warm, the smallness serving intimacy, her final act ‘Où suis-je?’ perfect. The new king, though, is Cyrille Dubois as Hippolyte. Dubois, a young singer like much of this excellent ensemble, is maturing in his command of dynamics, carrying a delicate tone through a rich line. Think of a Baroque Juan Diego Flórez, delicious nasality included. As a group, it is these sensitive singers who enable Mijnssen to keep the strata of her family drama solid.

Hippolyte et Aricie runs for four more performances through June. (For the trailer click here.)

Casey Creel