United States Matthew Aucoin, Eurydice: Soloists, Orchestra and Chorus of Los Angeles Opera / Matthew Aucoin (conductor), Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles. 1.2.2020. (HS)

United States Matthew Aucoin, Eurydice: Soloists, Orchestra and Chorus of Los Angeles Opera / Matthew Aucoin (conductor), Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, Los Angeles. 1.2.2020. (HS)

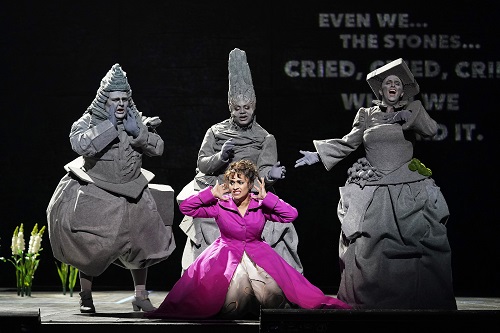

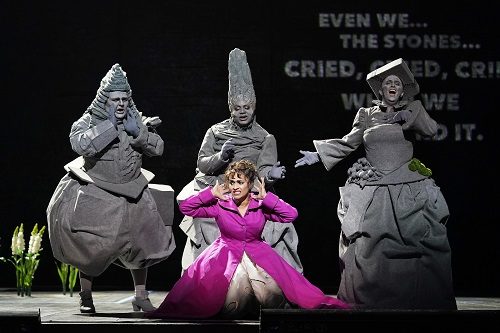

(Photo: Cory Weaver, courtesy Los Angeles opera)

Production:

Director — Mary Zimmerman

Chorus — Grant Gershon

Scenery — Daniel Ostling

Costumes — Ana Kuzmanić

Lighting — T.J. Gerckens

Choreographer — Denis Jones

Cast:

Eurydice — Danielle De Niese

Father — Rod Gilfry

Orpheus — Joshua Hopkins

Orpheus’s Double — John Holiday

Hades — Barry Banks

Little Stone — Stacey Tappan

Big Stone — Raehann Bryce-Davis

Loud Stone — Kevin Ray

The key moment in any telling of the Orpheus and Eurydice tale—the one that defines the story’s message—comes when Orpheus looks back at his wife as they try to escape, despite having been admonished not to do so. In classic Orpheus mythology, Eurydice is drawn back to the Underworld when Orpheus succumbs to his desire for her. (One might ponder a similar scene in the Bible, when Lot’s wife is turned into a pillar of salt.)

In Eurydice, the new opera from composer Matthew Aucoin and librettist Sarah Ruhl, the moment becomes psychologically more complicated. Among the many glosses that make this version more contemporary is Eurydice’s father; his presence in the Underworld makes her conflicted about leaving it, even for a husband who manages to make his way to hell to rescue her.

Aucoin’s score adds to the moment. The stately sound and pulse of the scene goes quiet before spinning off, not into crashing dissonances but into subtle hints of sadness and confusion. At the world première last Saturday evening at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, there were audible gasps around the audience.

The storytelling, based on Ruhl’s 2003 play that played off-Broadway in 2007, combines with the music to introduce a fascinating range of modern aspects. The big one, of course, is centering the story on Eurydice’s point of view. A dip in the river can erase a dead person’s memories, creating another hurdle for the characters to overcome.

Ruhl also portrays the Underworld god Hades as a sexual predator bound to remind audiences of men exposed in the #MeToo era. But she also peppers the libretto with welcome moments of wit. An accomplished poet, Ruhl has a wordsmith’s ability to write with deceptive simplicity, where plain language can hint at unexpected depth and the words create their own rhythms.

Aucoin, who turns 30 this year, has crafted a score that expands off of those words. His style ranges from vernacular to sophisticated. Dissonances are never jarring, and the orchestration brims with deft touches. His vocal writing settles engagingly into a wide range of voice types, and expands into several actual arias, duets and trios. Melodies can stretch into long sequences with too many sustained notes, but when they hover uncertainly at the end of phrases, the orchestra often seamlessly finishes the thought.

The composer defies expectations as much as Ruhl’s play does. The hero Orpheus is a baritone, not a tenor. A second singer—a countertenor—represents the character’s artistic spirit, doubling the part whenever Orpheus sings or thinks about music, creating a unique and appealing expansion of vocal tone and, often, harmony. Sometimes this spirit completes Orpheus’ thoughts.

The antagonist, Hades, is a high tenor with Rossini-esque melodic lines. Eurydice and her father, however, are exactly what you might expect—a lyric soprano and a rich-voiced baritone.

Soprano Danielle De Niese meets the challenge of singing throughout her range and sustaining those long phrases, all the while projecting a lively, youthful character whose addiction to books contrasts with Orpheus’ obsession with music. Baritone Joshua Hopkins, who sang the role of Harry Bailey in San Francisco Opera’s 2018 première of Jake Heggie’s It’s a Wonderful Life, ably carried the musical and dramatic line of Orpheus as a ‘regular guy,’ and countertenor John Holiday sailed affectingly over the top as Orpheus’ spirit.

Baritone Rod Gilfry (who actually appeared in Aucoin’s first opera, Crossing, in 2014) lent his mellifluous lower register to the proceedings as the father, and created a touching father-daughter rapport with De Niese’s Eurydice. At the other end of the male vocal spectrum, British tenor Barry Banks nailed plenty of high notes as Hades, and his acting caught the character’s smarminess.

The three members of the classic Greek chorus are represented as stones, a nod to the oft-repeated line that Orpheus’ music could make stones weep. At one point actual pebbles clatter to the stage from their eyes. These characters, clad as gray rocks of whimsical shapes, are portrayed by coloratura soprano Stacy Tappan as Little Stone, mezzo-soprano Raehann Bryce-Davis as Big Stone and tenor Kevin Ray as Loud Stone. Individually and as a trio they mock the humans and go a long way toward setting the opera’s smartly magical and foreboding tone.

An offstage chorus completes the musical arsenal, often bringing sweet harmonies into the mix.

In 2002, director Mary Zimmerman showed a flair for fancifully enlivening mythological plays in her Tony Award-winning turn with Metamorphoses. Here she starts with Eurydice and Orpheus in a brightly lit beach, to establish the characters as youthful and not very self-aware. In following scenes, spicy innovations introduce a booth that rises into the beach from the Underworld with the father penning a letter to Eurydice, an elevator that descends from the flies and rains on its occupants, and a penthouse where Hades tries to seduce Eurydice on her wedding day and with a loaded drink, makes her dizzy enough to send her tumbling to her death and into the Underworld.

It all conspires to make an entertaining evening. Aucoin’s music and Ruhl’s libretto provide enough heft with more to chew on than one might expect, which bodes well for this production when it’s presented next season at the Metropolitan Opera. The current Los Angeles Opera run extends through February 23.

Harvey Steiman