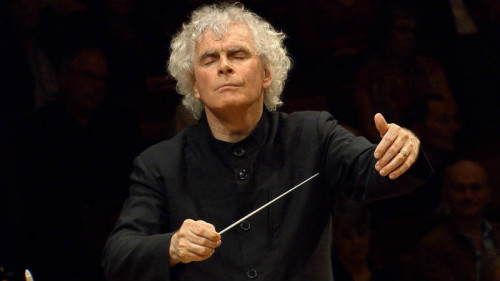

Germany Strauss and Beethoven: Jonathan Kelly (oboe), Iwona Sobotka (soprano), Benjamin Bruns (tenor), David Soar (bass), Berlin Radio Chorus (chorus director: Simon Halsey) / Simon Rattle (conductor). Philharmonie, Berlin, 5.3.2020. (MB)

Germany Strauss and Beethoven: Jonathan Kelly (oboe), Iwona Sobotka (soprano), Benjamin Bruns (tenor), David Soar (bass), Berlin Radio Chorus (chorus director: Simon Halsey) / Simon Rattle (conductor). Philharmonie, Berlin, 5.3.2020. (MB)

Strauss: Oboe Concerto in D major

Beethoven: Christus am Ölberge, Op.85

Not all conductors make for excellent accompanists, but such has long struck me as a particular strength of Simon Rattle. At any rate, so it was on this occasion, Rattle leading the Berlin Philharmonic in Strauss’s Oboe Concerto: beautifully shaped, yet never unduly moulded; full of telling chiaroscuro. Jonathan Kelly’s account of the solo part perfectly complemented such playing, offering a true sense of having risen from within the orchestra’s ranks – empirically true in this case too! – to spin a magical line both vocal in quality and beyond the capabilities of the voice. Orchestral woodwind echoing and shadowing the soloist heightened such magic, in a detailed performance that was yet quite without indulgence. The first movement offered greater variation of mood than one often hears, much to its expressive, formal advantage. Transitions between movements were expertly handled, first by Rattle, then by Kelly, Strauss’s Goethian conception of metamorphosis vividly, meaningfully apparent. A songful slow movement, never exaggerated, led to a finale of Elysian lightness. Who, after all, could resist Kelly’s duetting with Emmanuel Pahud, or such cultivated string playing? And why would anyone wish to try? Imbued with all the melancholic cheer of an Indian summer, this was as fine a performance of the work as I have heard.

A true rarity followed: Beethoven’s oratorio, Christus am Ölberge. Rattle has been touring the work with the LSO, so perhaps a recording is in the offing. On the evidence of this performance, it would prove a welcome addition. The opening Introduzione struck me as especially well judged: not unduly ‘symphonic’, but rather an opening to something one might have guessed to be a vocal work if one did not know. The chamber orchestra employed for Strauss had been somewhat expanded; Haydn’s presence was discernible, yet neither here nor elsewhere was this music simply to be reduced to influence from forebears. Already, as throughout, there were distinct flashes of something closer to Fidelio. Benjamin Bruns’s opening, unaccompanied recitative, sweet-toned and lyrical, suggested an inspired choice of casting, a suggestion furthered as the work progressed. Like Beethoven, one must endure a dated and at best mediocre libretto, very much run-of-the mill Aufklärung, but when the orchestra re-entered, it prepared psychological advances such as those mere – often very ‘mere’ – words could never have anticipated. The post-Mozartian agitation of Christus’s following aria speaks in somewhat generalised terms: Idomeneo without the focus, one might say. That said, Bruns not only brought an extraordinary command of colour – the wanness of ‘nahen Grab’, for instance – but also, alongside the Berlin woodwind, a growing sense of that most indispensable Beethovenian quality, hope.

Iwona Sobotka’s recitative and aria as Seraph travelled with ease between truly hochdramatisch delivery and greater intimacy: operatic, then, in the best sense. Her coloratura glittered yet never for its own sake, put to excellent musico-dramatic use. Echoes of The Creation, long a favourite Rattle work, were clear; so too, I think, was an affinity in the aria’s central stanza with The Magic Flute. In both cases, there are decidedly worse models to follow. Once the first-rate Berlin Radio Choir had entered, the number became ever more developmental, Beethoven’s symphonic inclinations here, as in later numbers, offering intriguing, individual, and for the most part highly convincing formal solutions. Such was certainly the case in the ensuing duet between Christus and Seraph and the choruses following, the dated libretto if anything heightening the sense of formal innovation. Again, Fidelio, or at least Leonore, beckoned. There were times when I felt the music would have benefited from being taken less hurriedly, but I should not exaggerate; other tempi were more judiciously chosen.

David Soar’s human Petrus, consoled by a Christus palpably increasing in strength and resolve, heralded a delightful return from Sobotka’s Seraph. An heroic last hurrah from Bruns’s Christus, ready to brave and vanquish Hell, proved just the herald for a closing chorus strikingly reminiscent both of Mozart (La clemenza di Tito) and Haydn (The Seasons). Once more, Beethoven and his performers chose their models well, finding inspiration rather than constraint in them.

Mark Berry