It will come as a surprise to no one that Andy Warhol was a mother’s boy. And Catholic to boot. As soon as he moved into what would much later be called the Factory, mum Julia moved in with him. She was already in New York with her son. It would turn out that New York was ready for Warhol and Warhol for New York. Tate Modern has been especially attentive to the Catholic bit. The final room is devoted to Andy’s obsessive photographs of an obsessive misrepresentation of Leonardo’s Last Supper. It succeeds supremely in what I guess is its objective. Anyone else for gathering nuts in May?

At the same time, the exhibition fails in the most abysmal way. It studiedly avoids any mention of Joe Dallesandro or the four films which Andy made of this young bisexual criminal who spent his life in and out of jail. More out than in jail, it has to be said, after Andy made him famous. The whole world knows every inch of Joe’s magnificent body. When I took a Victorian great aunt to see the UK premiere of Flesh (1968), she was intrigued by Joe’s sustaining a hardened erection with a bored look on his face. Keep in mind, this was many decades ahead of the superbly sculptured Olympic gay diver, Tom Daley. The American critics went wild with enthusiasm for Joe. Not so the British press.

The four films with Dallesandro superstar were directed by Paul Morrisey (sometime Warhol’s lover) and is an open, frank celebration of the male body which has never been surpassed. Joe’s look of boredom upped the sexuality in his performances. A then new way of understanding sex. (Joe – now 71 – married three times, producing three sons and also grandchildren.)

There appears to be some problem with the copyright of these films. The giants all want to buy them, but on a good day, you can still watch them live on YouTube without payment. Tate Modern ought to have used its powers and be in a position to buy them outright, for which they would easily have found a sponsor. Pussyfooting around honesty is always unforgivable. Though I guess Warhol would flicker a wry smile, rather than turn in his grave.

Andy’s birthplace of Pittsburgh (1927) sounds like a place of mind-numbing dullness. As the youngest son, Andy used a small legacy his dad had left him to study the only thing which had a hint of colour – and thus of hope – in it: advertising design. This entailed drawing and painting as well as photography -all three of which would prove fundamental to his craft. He always held that his work was more craft than art. It was always the craft which engaged him, with a cautious admission of the art. Never the other way round. That trinity of drawing, painting and photography would later have to expand its third person to include film. It delighted him to have made Joe Dallesandro internationally famous, before he was famous himself.

New York was already buzzing with these three crafts. Merce Cunningham became a friend, having freed choreography more than a notch or two from the training – already considered freed- he had received from Martha Graham. (There must be something in this freeing up: Graham and Cunningham both lived till their late nineties.)

Cunningham’s lifetime partner, John Cage, was another Warhol influence. Cage believed we were not attentive enough to the aural auditions which accost us on a daily basis, and he devised many ways of bringing these sounds centre stage, sometimes in collaboration with Cunningham choreography. I Ching, which prompts unexpected free choices, formed a basis of this thinking. You won’t know till you’ve done it. But that is an oversimplification of a complex school of Chinese philosophy.

I was not in the UK when Cage and Cunningham took over the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. But a friend who was, points out to me on our every visit to the Tate, how inventively choreographer and composer engaged with this huge, challenging space.

Marcel Duchamp (1887 – 1968) was another Warhol influence. As well as the preferred chess partner of John Cage. Chance operations, of course. The final decades of Duchamp’s life were in New York. He was authoritative enough to be able to declare that anything he signed would become ipso-facto a work of art. Warhol seized on the idea with glee. Some argue that he overdid it. I disagree. He was having fun. And that fun communicates itself. So loud applause from John Cage for that.

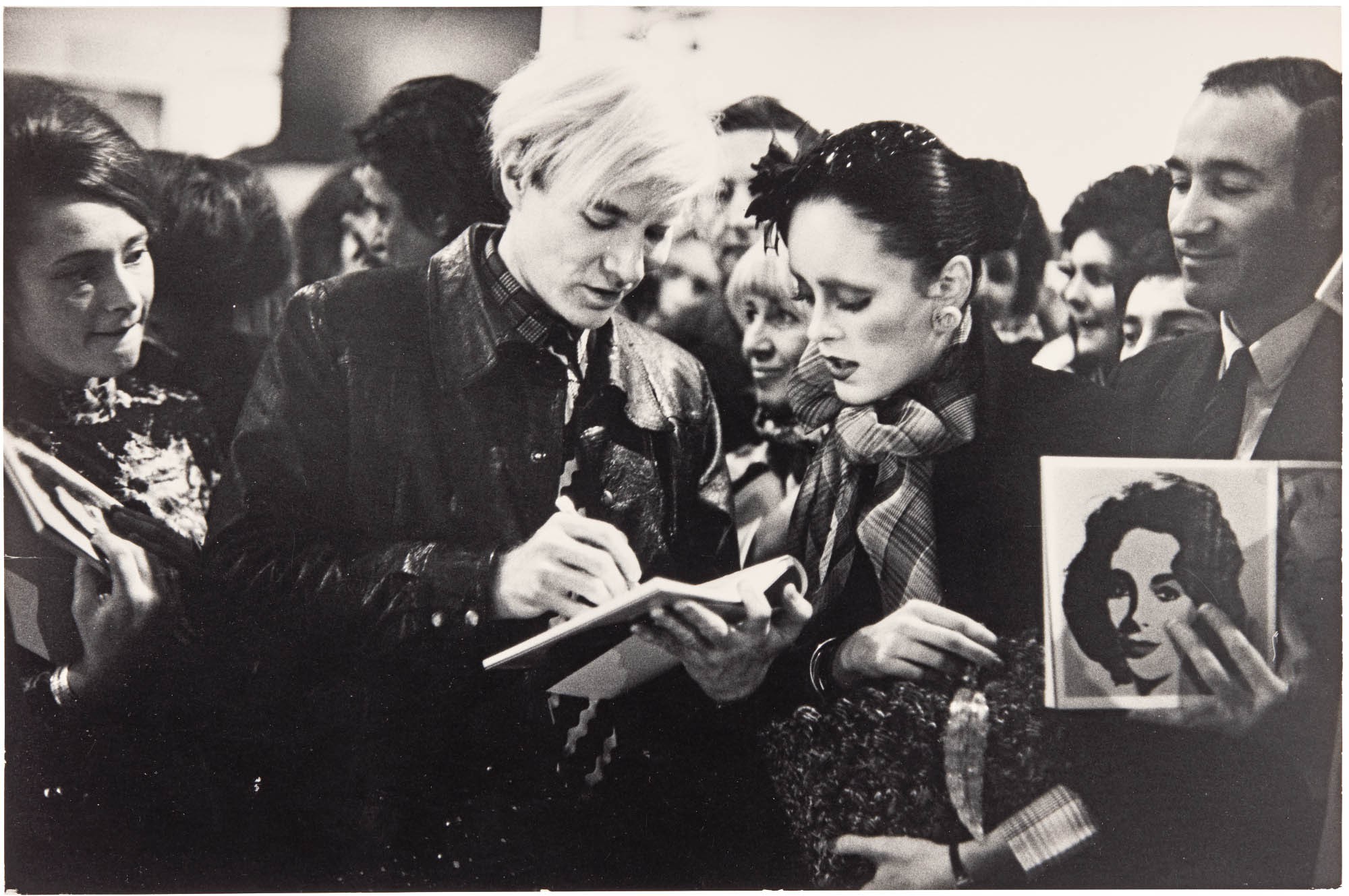

Photographs are valuable because they tell you much about a person in a single shot. Much more than words and even more than an artist’s portrait. The artist will consider which aspects of his subject to bring out and which to mute; inevitably something of the artist himself appears in his work. Most of the Warhol portraits were taken as stills – during short shoots – with the subject looking into the camera.

Choreographer Lucinda Childs looks like a good-luck doll that you could comfortably put into your pocket. She barely moves a muscle. Nor is she smiling. There is something steely in this beautiful doll. You may see her differently. Ambiguity is always a virtue in Warhol.

In contrast, Susan Sontag is smoking a cigarette – the business of which eventually killed her. (This was long before she had written Illness as metaphor.) Today’s audiences will pick up on the death-throw indicator. Would Susan have banned the photo if she had known it would be on display at the Tate some decades later? I think she might.

There is also a most moving portrait of Bob Dylan, where in absolute stillness, he seems not to breath while exuding an undefinable mystic energy.

Marcel Duchamp is one of the few that wasn’t taken at the Factory. The photo is grainy and looks as though he wishes he were playing chess instead. The craft is nothing like as perfect as the others, as Andy would surely have been the first to agree.

My own way of punishing Mao was to always refer to him as Chairperson Mao: political correctness to a t. Warhol famously went in for gigantic Mao portraits. To most eyes there would be a strong element of irony. As well as admiration for the People’s Leader. Mao gets a wall to himself as does Marilyn Monroe in the well-known, somewhat distorted photos.

Commerce gets its space in the exhibition too, notably with Brillo pads and Campbell’s soup cans. Even those who have never heard of Warhol, know this publicity stunt. It earned the artist millions. And gave serious art another dimension.

Andy Warhol has been extended at Tate Modern till 15 November for more information click here. Admission only by pre-booked ticket £22. Members of Tate Modern go free, though pre-booking is still required (telephone 0207 887 8888).

Jack Buckley