Austria Rudolf Nureyev’s Der Nussknacker (The Nutcracker): Dancers of Vienna State Ballet, Orchestra of Vienna State Opera / Kevin Rhodes (conductor). 27.12.2018 performance at Vienna State Opera House, reviewed as a livestream (directed by Balázs Delbó). (JPr)

Austria Rudolf Nureyev’s Der Nussknacker (The Nutcracker): Dancers of Vienna State Ballet, Orchestra of Vienna State Opera / Kevin Rhodes (conductor). 27.12.2018 performance at Vienna State Opera House, reviewed as a livestream (directed by Balázs Delbó). (JPr)

Production:

Music – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Choreography and direction – Rudolf Nureyev (rehearsed by Manuel Legris)

Sets and costumes – Nicholas Georgiadis

Lighting – Jacques Giovanangeli

Cast included:

Clara – Natascha Mair

Drosselmeyer / The Prince – Robert Gabdullin

Fritz – Arne Vandervelde

Luisa – Rikako Shibamoto

The Father – Alexandru Tcacenco

The Mother – Emilia Baranowicz

Two Snowflakes – Ioanna Avraam, Nina Tonoli

Spanish dance – Rikako Shibamoto, Arne Vandervelde, Vanessza Csonka, Gala Jovanovic, Oxana Kiyanenko, Giovanni Cusin, Andrey Teterin, Zsolt Török

Arabian dance – Zsófia Laczkó, Eno Peci, Beata Wiedner, Gabor Oberegger, Marie Breuilles, Laura Cislaghi, Joana Reinprecht

Russian dance – Emilia Baranowicz, Alexandru Tcacenco, Alena Klochkova, Iulia Tcaciuc, Oxana Timoshenko, Chiara Uderzo, Marat Davletshin, Marian Furnica, András Lukács, Kamil Pavelka

Chinese dance – Marcin Dempc, Trevor Hayden, Géraud Wielick

Pastoral – Fiona McGee, Isabella Lucia Severi-Hager, Scott McKenzie

In 1958, Rudolf Nureyev – then only 19 and still a student at the Leningrad Ballet school – first danced the role of the Prince, in a revival of Vasili Vainonen’s famous 1934 The Nutcracker. It is suggested that this production inspired the first one he staged for Swedish National Ballet in 1967. With new designs from Nicholas Georgiadis – who he had worked with on his Vienna Swan Lake in 1964 (click here) – Nureyev restaged his The Nutcracker for The Royal Ballet in 1968. I saw him dance the dual roles of Drosselmeyer and the Prince once – and once only – at Covent Garden several years later in 1977. It is this version that Manuel Legris – who danced for Nureyev in Paris – revived for Vienna State Ballet in 2012 and we saw in this 2018 performance.

Nureyev’s Freudian version takes place, of course, on Christmas Eve, and Georgiadis has suggested we are shown 1905 fin-de-siècle Russia and The Nutcracker begins with skaters and some young men frolicking as the guests arrive – at an impressive villa frontage – for the Stahlbaums’ party. (Is it me or does this opening scene remind you of Wayne Eagling’s current English National Ballet Nutcracker?) The costumes are traditional – and typically Russian – with elegant ball gowns and gold-braided officers’ uniforms. There will later be Hussars on horses (well, of sorts!). The decorations are as realistic and elaborate as the costumes, with a large candlelit tree to the rear of a candlelit salon.

Drosselmeyer is the godfather of the Stahlbaums’ eldest daughter, Clara, and is given a piratical eyepatch and limp. He brings her a white Nutcracker doll before entertaining the dozens of children looking like an eccentric wizard in his cloak of many colours. (It is Drosselmeyer’s appearance that was my abiding memory from 1977.) Nureyev includes – just like Vainonen – Drosselmeyer’s puppet show which foreshadows the subsequent fantasy scenes by showing a prince, a princess, and a rat king as characters. There is a charming solo for a reflective Clara before her brother Franz breaks her beloved doll and Drosselmeyer repairs it. It has all been a bit too much for Clara who falls asleep as the clock strikes twelve.

Matters now take a psychoanalytical turn as Clara dreams she is menaced by 18 scurrying rats and her Nutcracker doll becomes her white knight and eventually – after things don’t go that well for the battling toy soldiers and Clara has been surrounded – he vanquishes a huge Rat King. Clara’s doll transforms into the Prince her pubescent heart desires and there is a delightful duet, before a joyful solo for the Prince, twenty-six sparkling Snowflakes, and the calming singing of the Opera School of Vienna State Opera, brings the first act to a close as snow gently falls.

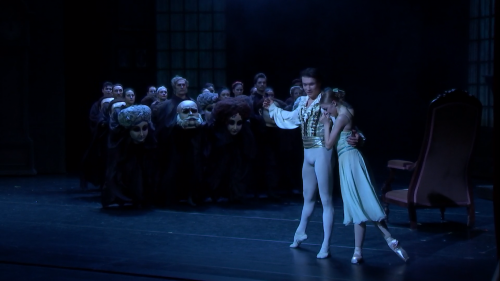

The longer second act is something different with just one extended dream sequence after another and more Freudian imaginings. Near the beginning is a nightmarish sequence as the familiar faces of family and friends from around the Christmas tree appear as bats with huge heads, with one, appropriately, looking like Austria’s Emperor Franz Josef. It is now Drosselmeyer who transmogrifies into the handsome prince. He takes Clara around the world and we see some of those faces again in the Spanish, Arabian, Russian, Chinese, and Pastoral dances – before the pair (and not the usual Sugar Plum Fairy and her Cavalier) end up in what looks like The Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles for the most sublimely classical of all classical ballet’s pas de deux. As a coda, Drosselmeyer picks up the sleeping Clara – still clutching her Nutcracker doll – who eventually wakes up as he and the other guests depart with Clara finally seen following Drosselmeyer out of the front door.

And how was the dancing you may be wondering by now? Robert Gabdullin looks a youngish dancer, though he smoothly switched between the older, ‘silver fox’ Drosselmeyer and the boyish fairy-tale Prince. (Doesn’t his Drosselmeyer look like his late Russian compatriot, Dmitri Hvorostovsky, and didn’t his Prince bear a passing resemblance to a young Nureyev?) The choreography Nureyev gave himself and the other men is increasingly familiar from the more of his creations you get to see, and Gabdullin does well with the fast, tricky step combinations, extended arms, suspended leaps, held poses, and fast turns. Importantly, Gabdullin was also a selfless partner and knew exactly how to present his ballerina to the audience in the best way.

There were two reasons to see Nutcracker: firstly, for me to return to a Nureyev staging I once saw over forty years ago, and secondly, to see Natascha Mair dance Clara. She is English National Ballet’s newest principal dancer having joined from the Vienna State Ballet. (Click here for my review of her debut performance in ENB’s recent Nutcracker Delights.) Nureyev gives Clara many more opportunities than I saw then but my initial impression of this remarkable young dancer has been confirmed. On the very night of this performance, Mair was promoted – at 23 – to First Soloist at the curtain call (the company’s equivalent of principal); so her meteoric rise is to be followed closely when dancers eventually can get back on the world’s stages. Mair already performs here with a rare naturalness and never – at any time – do you see her open face register the technical demands of the choreography and her dancing has lightness, speed, and an easy fluency. Mair’s vivid response to the music seems instinctive and she seems to have the ability – not given to all ballerinas – to embellish a phrase to stress the rhythm and intrinsic emotion.

It was a wonderful ensemble performance from the Vienna State Ballet’s stylish soloists and the impeccable synchronicity of their corps de ballet all appearing committed to Nureyev’s desire for almost constant movement.

Arne Vandervelde and Rikako Shibamoto entered spiritedly into the siblings’ high jinks as Fritz and Luisa and returned in the lively Spanish dance; whilst Emilia Baranowicz (Mother) and Alexandru Tcacenco (Father) led an athletic Russian dance. Standing out in these variations were Zsófia Laczkó and Eno Peci in the entertaining Arabian dance as a sultan appears to entertain his harem before Laczkó and (the very flexible) Peci’s sinuous duet ends up with them picking the pocket of their master Gabor Oberegger (Grandfather).

The music for any ballet performance is often sadly neglected but the contribution of the Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera under Kevin Rhodes could not be faulted – from what I heard – and they highlighted all the infinite reserves of melodic inspiration, Russian vividness, and vitality of some of Tchaikovsky’s most delicious music.

Jim Pritchard

For more about events from Vienna State Opera during their current lockdown click here.