United Kingdom Prom 43 – Kurtág, Fin de partie (Endgame, semi-staged, UK premiere): Soloists, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra / Ryan Wigglesworth (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, 17.8.2023. (CC)

United Kingdom Prom 43 – Kurtág, Fin de partie (Endgame, semi-staged, UK premiere): Soloists, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra / Ryan Wigglesworth (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, 17.8.2023. (CC)

Semi-staging:

Stage director – Victoria Newlyn

Cast:

Hamm – Frode Olsen

Clov – Morgan Moody

Nell – Hilary Summers

Nagg – Leonardo Cortellazzi

It is a miracle in itself we have this piece, of long gestation, from the 97-year-old composer Gyorgy Kurtág – and it is probably not complete, as yet. The subtitle is ‘Scenes and Monologues’ and it is far from a complete setting of Samuel Beckett’s play. This BBC Prom performance, though, in no way it was presenting a work in progress; instead, the impression from first to last was of the privilege of attending the country premiere of a major opera.

The plot of Beckett’s Fin de partie is as elusive as Kurtág’s music. We have the blind Hamm in his wheelchair, his servant Clov, and his dustbin-bound parents Nell and Nagg. Even Kurtág himself said he cannot tell the story – ‘it’s about the whole of human life … c’est fini, peut étre’ is one comment in interview (quoting early lines, in French, from the opera).

While the piece sets only part of Beckett’s play, it is certainly text-driven, with the orchestra illuminating the words – and, more specifically, the emotions – throughout. The text is about death, endings and bleakness of existence (Clov in particular enduring more than a touch of Groundhog Day in his daily activities), and yet Kurtág’s music has an inner glow that speaks of hope. Kurtág’s sonic palette is infinitely varied, using an orchestra that includes cimbalom, part of a ‘continuo group’ of harp, grand and upright pianos, cimbalom and celesta, a combination capable of great sonic beauty.

Although most of Kurtág’s music has been on the micro-level, and short, listening to this piece it is no surprise that the opera succeeds. The delicacy, the attention to every detail, is everywhere apparent, following and reflecting the text or creating the most rarefied of atmospheres in which every note, every phrase, counts so much. It’s like a tiny miniature, just exploded outwards to last nearly two hours. It’s like Webern, and just as beautiful, but expanded. Two hours it might be, but not one note is wasted.

One of the offshoots of that concentration of the music was the concentration of the audience – one of the quietest Proms audiences I have ever encountered. Even the fairly regular stream of people vacating the premises tended towards silence. Kurtág’s music draws the listener in, compellingly. To interrupt is to interrupt something holy (or perhaps more than that).

Conductor Ryan Wigglesworth has studied Fin de partie with Kurtág, and how it shows. His knowledge of the score was everywhere apparent, his every gesture meaningful. The members of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, already shown to be on top form this season in a spectacular Beethoven Ninth under Wigglesworth (review here), showed their virtuosity in another way: pin-point accuracy, and total control over their instruments – no easy ask given the predominantly low dynamic and Kurtág’s use of registral extremes.

The opera begins with the only passage in English: the poem Roundelay sung, unforgettably, by Hilary Summers (later, she is situated in the left-hand bin). Victoria Newlyn’s staging makes fine use of the available space, with Hamm to the right, isolated, the perfect space for his ruminations. Frode Olsen is superb as Hamm, the music part of the fabric of his being; he is a born narrator., each word audible, each word perfectly placed. He, like three of the four singers, has been with this opera from the start, a series of six performances at La Scala, Milan, in mid-late November 2018 (Summers and Leonardo Costallazi were there too; the original; Clov was Leigh Melrose, replaced here by Morgan Moody, who recently performed the piece in Dortmund in March and May this year; the original director was Pierre Audi).

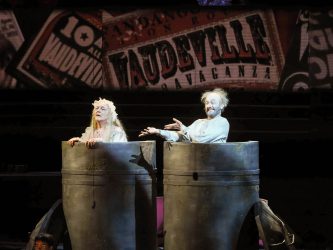

In contrast to the rather more static Hamm, Clov seems terminally unsettled, fussing in the second scene (‘Clov’s Pantomime’). His situation is unsurprising – when, in the tenth scene (‘Vaudeville’), Hamm dismisses Clov, Clov says his master has never spoken directly to him until now, as he is leaving. One aspect of the opera is about how the characters are trapped, whether in dustbins (resulting in the relationship claustrophobia between Nagg and Nell) or in situations. Eventually, Hamm realises he is the only one left playing the ‘Endgame’.

Moody captured Clov’s plight perfectly. Nell and Nagg, contralto Summers and tenor Cortellazzi respectively were faultless, Summers in particular offering moments of sublime vocal beauty. Sometimes those moments were, like Kurtág’s writing, glacial. And yet within that iciness is warmth and humour: warmth in recollection (the touching memories of the Ardennes heard via Nagg and Nell in Scene 3, memorably entitled simply, ‘Bin’) and humour in the earlier sections of ‘Vaudeville’ (and elsewhere, for sure) and perhaps dark humour in the macabre waltz of Hamm’s monologue.

Kurtág can be heard to reference earlier composers. Not just Webern, but Debussy and Stravinsky, perhaps. Touchingly, an open fifth is ‘Márta’s interval’ – Kurtág’s wife (they enjoyed an extraordinarily long marriage) who died in 2019. But Kurtág’s music is his own, without doubt. Hypnotic, compelling, it dares one not to lose attention for just a second – for in that second, one might miss universes.

This has to be one of the most significant Proms for many years. Kurtág’s opera is a masterpiece for the ages. It is intellectually uncompromising and yet tender and moving on a deep emotive level. At the end of nearly two hours with no interval, all I wanted to do was to hear it again, The many years of gestation in Kurtág’s head have clearly paid off (well over 60 years).

Interestingly, even over radio broadcast, shorn of visuals, the piece succeeds brilliantly – I urge readers to listen to head to BBC Sounds urgently.

Colin Clarke