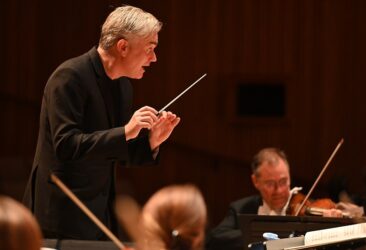

United Kingdom Beethoven, Bartók, Tchaikovsky: Christian Tetzlaff (violin), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Edward Gardner (conductor), Royal Festival Hall, London 30.9.2023. (JR)

United Kingdom Beethoven, Bartók, Tchaikovsky: Christian Tetzlaff (violin), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Edward Gardner (conductor), Royal Festival Hall, London 30.9.2023. (JR)

Beethoven – Overture, Egmont

Bartók – Violin Concerto No.2

Tchaikovsky – Symphony No.4 Op.36

Yet another interesting, exciting, entertaining programme and concert from the dependable London Philharmonic Orchestra under Edward Gardner.

To open the concert, a Beethoven overture: his Egmont, one of his better known. After a short dose of Sturm und Drang, characterful woodwind, finely blended horns and urgent strings combined to deliver a stimulating performance with which to raise the curtain.

Not by any stretch of the imagination can it be said that Bartók’s Second Violin Concerto is a crowd-pleaser. It is certainly not easy listening, for the most part. (Incidentally Bartók’s First Violin Concerto was rejected by its dedicatee, and Bartók deleted it from his catalogue of works. It was composed in 1906 but only performed fifty years later, after the composer’s death. It was revived by Paul Sacher and championed by David Oistrakh.) Bartók’s Second Violin Concerto stems from 1939 at a time when Bartók saw the fascist writing on the wall and sought exile in the United States. The concerto bridges a diatonic soundworld , and there are distinct hints at an evolving interest in twelve-tone composition though he is reputed to have told the young Yehudi Menuhin that he wanted to show Schoenberg that one could use all twelve tones and still remain tonal.

The concerto demands a virtuoso soloist and that is what it had in Christian Tetzlaff, to whom the work is not new. The concerto veers from the lyrical to Transylvanian folk melodies. The first movement, Allegro non troppo, has an unusually captivating harp and horn opening but soon turns frenetic, with trademark Bartókian string thwacks to further liven up the proceedings. Tetzlaff was movingly tender in the Andante tranquillo, its start bringing both Mahler and Britten to mind. The final movement, Allegro molto, is a brazen vehicle to showcase the soloist’s technical wizardry and mastery of his instrument. Tetzlaff often danced through the piece, particularly in the final pages, the audience in awe of his fingerboard skills. Introvert passages were reflective, extrovert passages fiery and captivating – a fine performance of a difficult work in every sense. Tetzlaff’s modern instrument by German luthier Stefan-Peter Greiner delivered a warm tone easily matching any Stradivarius or Guarneri del Gesù. Tetzlaff will now join the orchestra on its tour of South Korea in which he plays the Brahms concerto.

Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony needs no introduction except to remind readers that it was composed at a time when he felt constrained to marry Antonina Miliukova in order to quell rumours about his sexual orientation: in a matter of months this proved a disastrous decision. The theme of gloomy fate pervades the entire work, but its energy is infectious. The first movement, Moderato con anima, after the short Andante sostenuto, showed the orchestra in recording quality form – the performance will be relayed on BBC Radio Three on 4th October. Gardner piled attack upon attack: the trombone section in particular thrilled. Gardner relished every bar, controlled the dynamics to perfection, kept an extremely steady beat and, above all, injected plenty of Russian white heat and ferocity. Full marks for the solo contributions by oboe guest principal Rainer Gibbons and bassoon principal Jonathan Davies: the shrill piccolo of Stewart McIlwham frequently caught the ear. The strings shone in the pizzicato stretches of the Scherzo, particularly the fine double basses: notably an equal number of men and women in the double basses.

The hall seemed to shake with the fiery force of the Finale: Allegro con fuoco, even if the final pages cannot allay the fundamental negativity of this brutal work. It brought the house down.

John Rhodes