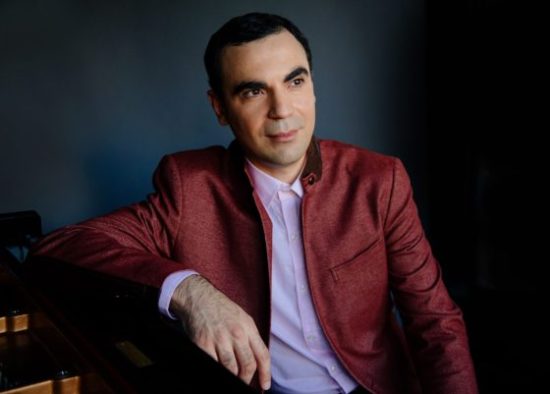

Italian pianist Sandro Russo talks to Robert Beattie

Chetham’s Music School in central Manchester run an International Piano Summer School every year for pianists of varying levels of ability including talented students, teachers and adult amateur pianists. As an enthusiastic amateur pianist, I decided to enrol on the course myself earlier this year. There were many distinguished professional pianists on the course teaching students and giving masterclasses. In the evening a number of the teachers gave concerts in Chetham’s Stoller Hall. It was amazing to hear such a wide and varied range of demanding repertoire being performed to such a high level.

I was struck by one concert, in particular, by the Italian pianist, Sandro Russo. Sandro performed all twelve of Liszt’s Transcendental Études and his performance was deservedly greeted with a standing ovation. Sandro technical command of these extremely difficult works was never in doubt. However, I was struck more by the way in which he was able to transcend the technical difficulties and to produce playing which was thrilling, dramatic and ravishing in turn while sustaining beauty of tone. It was one of the most dazzling pieces of live piano playing I have ever heard. You can watch Sandro performance here.

Sandro’s playing has often been referred to as a throwback to the grand tradition of elegant pianism and beautiful sound. Abbey Simon has praised him as ‘an artist to his fingertips…musical, intuitive, and a master of the instrument.’ Lowell Liebermann has called him ‘a musician’s musician, and a pianist’s pianist. There is no technical challenge too great for him, but it is his musicianship that ultimately makes the greatest impression. His interpretations reveal a unique and profound artist at work.’

Sandro displayed exceptional musical talent from an early age. After entering the V. Bellini Conservatory, from where he graduated summa cum laude, he went on to earn the Pianoforte Performing Diploma from the Royal College of Music in London with honours. While still a student, he won top prize awards in numerous national and international competitions, including Senigallia and the Ibla Grand Prize. He moved to the United States in 2000 where he won the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra Concerto Competition, which led to a performance of the Liszt A major Concerto at the Bergen Performing Arts Center in Englewood, New Jersey. Shortly thereafter, he gave an acclaimed Chopin recital at the prestigious Politeama Theatre in Palermo, Italy, and later appeared at the Nuove Carriere Music Festival, an international showcase for the world’s most promising young musicians.

Sandro has gained attention for an extensive repertoire that is comprised not only of well-known works from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries but also piano rarities. He has given acclaimed virtuoso performances of works by György Cziffra, Kaikhosru Sorabji and other composer-pianists, as well as by Lowell Liebermann, Paul Moravec and Marc-Andre Hamelin. As a soloist or in recital he has appeared in many of the world’s leading venues including the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, the Konzerthaus Berlin, Salle Cortot in Paris, Teatro Politeama in Palermo, Weill and Zankel halls at Carnegie Hall and Nagasaki Brick Hall in Japan.

In the summers of 2017 and 2018, Sandro gave solo recitals in the recently opened Stoller Hall at Chetham’s Music School in Manchester. He also performed in London and Vienna, and in September 2017, he had the honour of performing with the world-renowned soprano, Sumi Jo, for the president of South Korea, to promote the PyeongChang 2018 Winter Olympics. In October 2018, he gave a highly praised performing in the Fernando Laires Series at the Eastman School of Music’s Kilbourn Hall (Rochester, NY). Sandro’s performances have aired on major radio stations in the US and abroad and he has released a number of critically well received recordings notably Images et Mirages: Hommage à Debussy in October 2018 on the Steinway & Sons label. That release was chosen as ‘Disc of the Month’ by Italy’s Classic Voice magazine and was also featured in Gramophone’s ‘Sounds of America.’

Robert Beattie: Sandro, I was hugely impressed by your performance of Liszt’s Transcendental Études at Chetham’s Stoller Hall earlier in the year. Can you please tell us what drew you to these works?

Sandro Russo: I’ve played a few of the Transcendental Études throughout my career. I played the 10th Étude when I was a teenager and I added a few of the other études to my repertoire over time, including No.5 (Feux follets) and No.8 (Wilde Jagd). I never really thought about learning the whole set until lockdowns were imposed during the Covid pandemic. This provided the necessary time and motivation to look at all the études in the round. I previously found I was not connected to some of the études the same way as those I had already performed in concert, but this period of intensive study allowed me to forge a better connection to these works. I certainly got to fully appreciate some of the études which are less well-known, like No.6 (Vision) and No.7 (Eroica), for instance. Embarking on the whole cycle also influenced quite a bit the way I played some of the études which were already in my repertoire and made me see each étude more in the context of a much larger structure of ‘operatic’ proportions.

RB: Which of your teachers were you most influenced by as you studied to become a pianist?

SR: I had quite a few piano teachers prior to completing my studies at the V. Bellini Conservatory in Palermo, Italy. One of the major turning points in my piano playing, however, happened when I attended a series of masterclasses by the renowned Russian pianist, Boris Petrushansky. In those days, I saw him as a personification of the ‘romantic school’ of piano playing and learned so much from him on making the piano truly ‘sing’! After moving to the US in 2000, I had regular private lessons with Seymour Bernstein, while pursuing my master’s degree in Piano Performance in the class of Jeffrey Biegel, who was a former pupil of Adele Marcus at the Julliard School in New York. Despite their representing two different musical generations (being some 35 years apart from each other!), both bore strong ties to those legendary schools of piano playing such as Josef Lhévinne’s (Adele Marcus’s teacher), or Sir Clifford Curzon’s and Alexander Brailowsky’s (Seymour Bernstein’s mentors). One common element in their teaching which I found very appealing to my musicianship was their high regard of the so-called ‘Golden Age,’ and its relevance to forging interpretations of the present.

RB: Which pianists do you most admire?

SR: I tend to have a natural admiration for pianists from the ‘Golden Age’ such as Moiseiwitsch, Rachmaninov, Hofmann and Horowitz, of course! Their performances are highly individualistic, but they always played in a way which illuminated the composer’s intentions in the score. Other pianists that I have grown to admire more and more include Bolet, Cherkassky, Gilels, Michelangeli and Arrau.

RB: Michelangeli was unusual for pianists of that stature in that the range of repertoire he chose to perform in public was relatively small although I gather he had a vast repertoire in private. Bolet and Arrau are both associated with the music of Liszt and I think both have recorded the Transcendental Études.

SR: Yes, I have also heard that Michelangeli had played a much wider range of repertoire in private. As for Bolet, I love the poetry that transpires from his playing. He did record Liszt’s Transcendental Études although he did alter the order in which they are normally played. Arrau was taught by Martin Krause who was a student of Liszt so he had a direct connection to the composer. As he got older, he seemed to be increasingly concerned with bringing out the poetic message of the music and his sound was ravishing. Arrau’s technique was rock solid, and it was evident from everything he played. He recorded Liszt’s Transcendental Études at the age of 75 I believe, which is amazing, and it shows what an extraordinary control of his technique he had.

RB: Arrau’s later recordings are somewhat controversial as he adopted very slow tempi for some pieces. I like his performance of the Transcendental Études particularly No.12 (Chasse-neige) although I find his performance of No.5 (Feux follets) a little slow.

SR: It is true that Arrau adopted slower tempi as he got older, although one could argue that he was letting other aspects of the music ‘breathe’ more in his interpretations. Richter’s famous performance of Feux follets at his recital in Sofia in 1958 began a trend of playing this piece faster and faster, often at the expense of creativity. Arrau’s performance highlights other aspects of the piece, such as the shape of the musical line, the clarity of textures and a beautiful singing tone.

RB: I understand you recorded a DVD on the historical 1862 Bechstein piano, originally owned by Franz Liszt. What was it like to play on Liszt’s piano?

SR: I was struck by the lyricism of the instrument and how close to the human voice it sounded. However, it was far from responsive in terms of its action. I was only allowed to play a few short lyrical pieces on the piano, as the instrument was still in its original state and treated more like a museum piece. It was a nice and sweet way to connect with Liszt’s sound world.

RB: I understand you also recorded a DVD on Horowitz’s CD-75 Steinway piano, and this represented the first recording made on this legendary instrument following Horowitz’s death. Can you tell us how this came about?

SR: Yes, I had the privilege of playing Horowitz’s Steinway that the Maestro used for legendary concerts at the Royal Festival Hall, the Met in New York and in Japan in the 1980s. I was always amazed by the range of symphonic sonorities Horowitz was able to draw out of his Steinway. Having the opportunity to play on Horowitz’s piano gave me a valuable insight on how he was able to produce these amazing effects. The instrument was owned by a piano tuner in Manhattan, but I recorded the DVD in a large living room in Connecticut, where the piano was housed for a while. I chose pieces by Mendelssohn, Chopin, Liszt, Scriabin, Rachmaninov and Medtner, including two of Horowitz’s ‘warhorses,’ i.e., the Scriabin Études Op.8 No.12 and Op.42 No.5.

RB: You have made a number of recordings now which have been well received by the critics. Can you tell us about these recordings and the repertoire you most enjoy playing?

SR: I am primarily drawn to the Romantic piano repertoire, although I do play works from the Baroque, Classical and twentieth-century periods, including some contemporary works, as well. Most of my recordings so far have focused on particular themes of the romantic and late-romantic literature. For example, one of my recordings, ‘Russian Gems’ featured repertoire by lesser-known Russian composers. Some of the works included on the disc are the Sonata in F Minor Op.5 by Medtner, a Fairy Tale by Julius Isserlis (Steven Isserlis’s grandfather), Taneyev’s Prelude and Fugue Op.29, and two Grigory Ginzburg transcriptions of Russian songs, among other things. I also included Balakirev’s Islamey on the disc, which is of course more well known! Another recording released on the 100th anniversary of Debussy’s death is entitled Images et Mirages. It includes two of Debussy’s original works (the two books of Images), together with ‘hommages’ (to Debussy) written by other master composers, and transcriptions of some of his orchestral works such as the Prélude à l’après-midi d’une faune and Fêtes. The Steinway & Sons label has also released recordings which focus on particular composers. One of them, Rachmaninov – Solo Piano Works, features the First Piano Sonata, the Corelli Variations, three Études-Tableaux, and some Earl Wild transcriptions of Rachmaninov songs.

RB: Rachmaninov’s First Piano Sonata is not played as often as it should be and deserves to be heard much more widely. I understand it is a technically very demanding work.

SR: Yes, it lasts over 35 minutes and it is very taxing to play. It is easy to become over absorbed in the romantic impetus of the music and lose sight of some of its arduous technical difficulties in live performances! The third movement in particular is quite tricky and requires a lot of emotional self-control.

RB: Can you tell us when your recording of the Liszt Transcendental Études will be released, and something more on recording them compared with performing them in concert?

SR: The Transcendental Études are in the postproduction phase now, and I’m still reviewing a few offers from record labels that are interested in releasing them. The process of performing these monumental Études in a studio setting is different from performing them in a concert hall. The studio allows you to get more ‘obsessive’ about certain textual details and to perfect them until you’re totally satisfied. It makes you realize in different ways from the ‘live’ setting how each one of these études is a true gem (or ‘tone poem’) in its own right. Even the opening Prelude has its own musical arch, and it is a perfect miniature in itself.

RB: As I mentioned, your live performance at Chetham’s was outstanding. Do you have any new projects you will be working on over the coming months which you want to tell us about?

SR: No particular project repertoire-wise. After the Lisztian ‘tour de force’ of the twelve Transcendental Études, I would like to offer varied programmes with more Beethoven (especially his Variations), Robert Schumann and Brahms, as well as Ravel, Scriabin, and Rachmaninov.

RB: Sandro, thank you very much for talking to us and I look forward to hearing your final recording of the Liszt Transcendental Études.

Robert Beattie

Wonderful to read this article Sandro. We are SO privileged to have you at SCC. How did we get SO lucky. My best to you