Robert Beattie in conversation with Cameron Menzies, Artistic Director of Northern Ireland Opera, and baritone Yuriy Yurchuk

I have been reviewing Northern Ireland Opera’s productions for some years (links to some of my reviews can be found here). I have been struck both by the very high quality and infinite variety of their productions. They have produced a string of more conventional operatic productions, including La bohème, La traviata and Tosca which have received glowing reviews from the Press. Opera Magazine commented: ‘Northern Ireland Opera’s La traviata suggests that the artistic director Cameron Menzies has at long last realised the region’s ambition to have a grand opera company truly deserving of the name.’

In addition, they have also produced several successful Broadway musicals including Sweeney Todd, Kiss me, Kate and Into the Woods. The Times commented on the latter: ‘Cameron Menzies’s production storms along with such irresistible zest and unflagging energy that it deserves packed houses throughout its run’. More recently, they have moved into the field of chamber opera and produced a smaller scale production of The Juniper Tree by Philip Glass and Robert Moran. The Stage commented: ‘Looks as good as it sounds’.

Northern Ireland Opera have produced a fascinating and again highly successful ‘Salon Series’ featuring opera, art song, cabaret and music theatre. These performances have taken place across different venues across Northern Ireland including the opulent rooms of Hillsborough Castle and the gloomy foyer of Crumlin Road Prison. Every year they run the ‘Glenarm Festival of Voice’ in the historic coastal village of Glenarm. Now in its thirteenth year, this event brings together BBC Radio 3 recitals, outreach events, performances by emerging artists and culminates in the Competition Finale. During the summer they run a song recital series in partnership with First Church in Belfast.

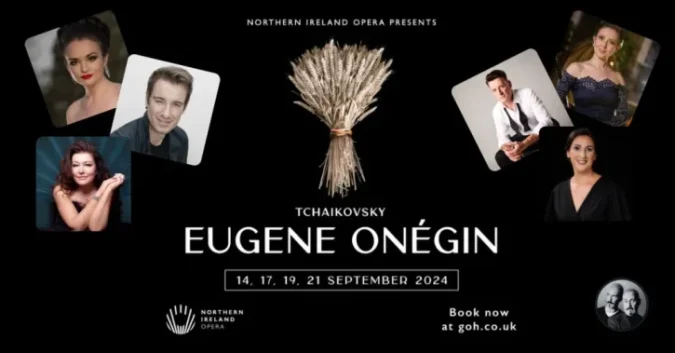

I spoke to the Artistic Director of Northern Ireland Opera, Cameron Menzies, and to baritone Yuriy Yurchuk about past and future productions. I spoke to Cameron about the challenges involved with taking up the role of Artistic Director in the middle of the Covid pandemic and the company’s successes during this period. I also asked him about the forthcoming production of Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin and other work strands the company are taking forward. I asked Yuriy how he approaches the role of Onegin and the challenges of this role. Yuriy is a British-Ukrainian citizen and he has made a number of statements about the current war between Russia and Ukraine. I spoke to him about the impact which this conflict is having on the world of classical music and for his views on this.

Robert Beattie: Cameron, you assumed your role of Artistic Director of Northern Ireland Opera during the Covid lockdown period. How did you negotiate the challenges associated with this period?

Cameron Menzies: I was appointed in October 2020 which I was still living in Australia. With all the restrictions I was not able to travel to Northern Ireland until March 2021 which was at that point completely shut down because of Covid. We were not able to do live performances, but we were able to film so I shot a 40-minute film called ‘Old Friends and Other Days’ which featured the music of William Vincent Wallace and one of his contemporaries, William Balfe, which won a series of awards around the world including in London, Paris and Madrid.

I took over the company at a time when there was no programming in place because everything had been cancelled. Normally, when you take over a company there is a grace period of 12-18 months when you can follow someone else’s programming and watch and see how things are done. The beauty of that challenge was that we could do what we wanted and tailor it to resources available to us. I couldn’t get venues to open because of Covid but we were able to do an opening production of Puccini’s La bohème in a beautiful, dilapidated old church in North Belfast called the Carlisle Memorial Church. This allowed me to reach out to several performers who were available due to the restrictions placed on them as a result of Covid. Yuriy was one of the people available and he sang Marcello for us in that production. So, while this period was challenging, it also presented opportunities; we were only able to get Yuriy at short notice as a result of the restrictions imposed by Covid. It allowed us to get some amazingly talented people into that production. We were only able to play to 100 people a night in the church. But we successfully raised the stage and sank an orchestral pit in the venue. There were about 35 instrumentalists in the pit, all of whom were freelancers from across Northern Ireland. Covid also presented opportunities as there were no rules around how best to come out of it. So, the situation provided us with the freedom to try out different new things.

RB: Northern Ireland Opera has a number of different work strands which it is taking forward at the moment. You have the main productions and the next one coming up in September is Eugene Onegin. You also have smaller scale productions, and also your highly successful Salon Series as well as a summer song recital series and the Glenarm Festival of Voice. Can you tell us about the different work strands you are taking forward?

CM: We obviously do grand opera in the Grand Opera House every year, but we also present opera on lots of different platforms across the 12-month period of programming. The Salon Series was something that I pitched when I was recruited as something that I would like to try. The first series consisted of six 50–60-minute concerts. They consisted of everything from French opera to chanson, Irish songs, theatre music and cabaret as a bit of a tasting plate across various musical genres to expose audiences to different things as well as works they may already know and love. It also allowed us to tour around Northern Ireland with a selection of varied music. The series has been a huge success and very well received by audiences across Northern Ireland. We started a second series on the 22 June in the Palace Demesne in Armagh with ‘The Stars, the Moon and the Georgian Sky’. This concert featured works by Gilbert and Sullivan, Handel, Poulenc, Verdi and Humperdinck celebrating the heavens. We have a programme of summer concerts at the Foyle Maritime Museum in Londonderry/Derry and the Flowerfield Arts Centre in Portstewart.

Earlier this year we produced two smaller scale productions: a pastiche to celebrate Valentines’ Day, ‘Cupid’s Bow’, and a Philip Glass/Robert Moran opera called The Juniper Tree which was based on one of Grimm’s fairy tales. These were both very successful as well. Both these productions played in the smaller Studio of the Grand Opera House and this gave us an opportunity to do some chamber work. We do try to provide opera in all different platforms and at all different entry points.

RB: Your next big production is Eugene Onegin. What do you see as the key challenges of staging this work?

CM: All great operatic works have their challenges. I’ve loved Eugene Onegin for a very long time; it is such a wonderful piece. Musically, it is one of the most satisfying pieces of opera ever written and it has some of the most moving music. It presents as a piece that fits Belfast and Northern Ireland very well in 2024. When I was thinking about singers that could perform for this production, I concluded there were very strong local female singers we could cast. The four female leads are all from Northern Ireland or from the north of Ireland. Mary McCabe, Sarah Richmond, Carolyn Dobbin and Jenny Bourke have been cast in those lead roles. I think that is a huge achievement for the company to cast these roles locally. Mary is making her main stage debut in her hometown. It also allowed Yuriy and I an opportunity to bring a project to fruition which we discussed in 2021 when we were doing La bohème. When I was thinking of casting the male roles, Yuriy was the person in my head to perform the role of Onegin.

Onegin works thematically for Northern Ireland and it also works thematically for the world. At a frivolous turn within the piece, two best friends set themselves on a tragic path they cannot come back from. Onegin kills his best friend Lensky and arguably metaphorically dies as well. The beautifully constructed duel which happens in that opera has universal impact. For me trying to capture that sense of two sides who won’t back down or try to find a way out of that conflict is a valid topic to be putting on an operatic stage or indeed any stage at the moment.

We have previously done La bohème, La traviata and Tosca; Onegin provides an opportunity to step outside of this Italian repertoire. It’s already proving very popular and tickets are selling very well. The music is very accessible and beautiful. If people love The Nutcracker and Swan Lake, they will absolutely fall in love with this as well. While every opera has its challenges, we try to meet them head on. With the cast and the team we have got it’s already proving to be an amazing experience.

RB: I sometimes think with Onegin you have the first two acts which are longer acts and you have the wonderful Letter Scene in the second act with Tatiana. And then you have the last two acts which are much shorter. In some ways it can be seen as a little bit unbalanced as an opera. Yuriy, do you have a view on that?

Yuriy Yurchuk: I think it’s a conscious choice by Tchaikovsky. Sometimes with movies, books or in theatre there is a lot of action but by the end of the work it has not made an impact and you don’t care what happens to the characters. This can happen because the exposition to the work does not properly introduce the characters to the audience. In this work you care about Lensky as you see him in the prime of youth and thinking about love and his future life. We end up rooting for the characters whether it be Lensky, Onegin or Tatiana. Tchaikovsky is very calculated and smart in this work in allowing us enough time to get to know the characters and ground ourselves in the story. The ending is very fast paced but he takes his time setting up the scene and allowing us to get to know the characters.

RB: I agree. The characters are beautifully formed and he’s using Pushkin’s wonderful poetry to help flesh out the characters. How do you approach the character of Onegin? He’s sometimes seen as very arrogant but there are also more nuanced aspects to the character.

YY: Some people say the opera should be called ‘Tatiana’ as she is the main character, and we see her journey through the opera from a young, inexperienced girl to the mature, sophisticated young woman we see at the end of the opera. When you play Onegin you cannot think of yourself as a bad guy. When you stand on stage you need to have your own reasons to justify your actions and what you say. His refusal to take up Tatiana’s initial declaration of love to him is often seen as arrogant but I don’t think that is the case. His main folly is his lack of moral compass but also his youth and inexperience. His main crime is killing his friend, it is not turning away Tatiana.

Onegin’s smaller crime takes place at the end of the opera when he declares love to Tatiana in spite of the fact that she is married. It was of course impossible at that time for a married woman to elope with another man without destroying her name and character. Onegin is more mature about the ways of the world and the court than his friend Lensky. In spite of this he does not take the necessary action to resolve the conflict without killing his friend. This is one of the things which makes this opera so relevant to modern audiences. It shows how events can escalate in the blink of an eye to an irreversible tragic outcome. It’s important for the audience to live through the events of the opera. In future conflicts to come it might remind people of the need to step back and take stock before allowing a conflict to escalate further.

RB: You have taken on leading roles in a number of Italian operas in the past including Marcello in La bohème and also in Un ballo in maschera and Andrea Chénier. How is the role of Onegin different to previous roles?

YY: Onegin is in Russian and this is my native language and what I grew up speaking. Tchaikovsky is often called the master of melody and you come out whistling some of the tunes from the opera. The journey of Onegin is also quite interesting to explore. Onegin shares the title role with Tatiana and it’s interesting to look at how this relationship develops. It is a very different opera to Andrea Chénier, which is a more heroic work. We need to remember that Onegin is only 18 during the time period of this work but he feels he has seen everything and done everything. You can see his initial rejection of Tatiana as an attempt to save this inexperienced young girl from making a fool of herself. The results are devastating for her as she has invested so much in this one guy and is building a castle in the air which Onegin then tears down.

RB: What are the vocal challenges of singing Onegin?

YY: There are challenges in the last scene where Tchaikovsky uses a rather thick orchestration. Onegin has been unable to get over the loss of his friend and he sees Tatiana as his one hope of salvation. Dramatically, you want Onegin to look into Tatiana’s eyes. However, you cannot do this as you have to project over large orchestral forces, so you need to face the audience directly. Tchaikovsky was a master of vocal writing and his score gives all the performers an opportunity to shine. You can her the amount of work he has put into the score in every phrase and set piece number.

RB: I sometimes wish opera houses would perform more Tchaikovsky operas in the West. Aside from Onegin and The Queen of Spades the other operas are rarely performed. In Russia and Eastern Europe the other operas are performed much more frequently.

CM: Iolanta is an amazing work but it’s probably harder to sell outside of Eastern Europe.

YY: We performed Iolanta in the Royal Albert Hall in the Spring under the baton of Vasily Petrenko. It is a great piece.

RB: Yuriy, I know that as a British-Ukranian you have expressed views on the recent conflict between Russia and Ukraine. In the classical music world some Russian singers have been banned from performances and Russian competitors have been barred from competitions as a result of the conflict. In the recent Queen Elizabeth Competition, the winning violinist refused to shake hands with a Russian judge. What view do you take of these issues?

YY: In some ways this is a complex issue but in my view it is also a simple one. The current Russian invasion of Ukraine is illegal, immoral and criminal. Every person in the civilised world is trying to help stop it or to assist those most affected by it. Northern Ireland Opera has done some work to try to raise donations for Ukraine. I am against discrimination based on someone’s personal characteristics whether that is race, gender or sexuality. I speak Russian myself and my girlfriend is Russian. However, discrimination based on what a person says or does is a different matter. I know a lot of Russian and Ukrainian artists who do not condemn the invasion and perform for Putin. Allowing these people to perform in the West and to benefit from the Western public seems wrong to me. I also know a lot of Russian artists who live in the West and who actively support Ukraine. Similarly, there are people who live in Russia who are opposed to the war and the current government although protest is becoming increasingly difficult in Russia. If Russian artists are opposed to the war then it does not seem right to discriminate against them.

There are some interesting ways in which Ukrainian culture affected Tchaikovsky and his music. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries there was an effort to assimilate Ukraine into the larger Russian empire and to deny the country its identity and right self-determination. Tchaikovsky’s family were from Ukraine and he spent a lot of time in the country. His opera Mazeppa features a Ukrainian hero. His music in many ways is influenced by both Russia and Ukraine and is a shared heritage for both countries. Tchaikovsky was an openly gay composer but many gay people in Russia face widespread discrimination nowadays. Tchaikovsky shows in Eugene Onegin how conflict and violence can emerge out of nowhere. It’s important to expose young people to the ideas in the opera and to show them the wider harm which violence can cause. If more young people are exposed to the ideas in this and other operas, perhaps they can help influence them to make better choices in future.

Most of my efforts in the last couple of years have been to bring as much attention to the war as possible. As the war drags on, it is not being reported so prominently in the news. It’s important to remind people around the world of the ongoing violence in the war and how it is impacting on the lives of ordinary Ukrainians. I believe we should do everything we can to support the people of Ukraine and to raise funds to help them.

RB: People sometimes do not realise that Prokofiev is a Ukrainian composer. He was born in a city located in modern-day Ukraine even though he is often seen as Russian. There is of course a great tradition of Russian musicians defying the official government policy. Rostropovich, for example, made his feelings very clear about the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia when he was performing the Dvořák Cello Concerto at the BBC Proms when he held up the score at the end of the performance. So, there is a role for Russian musicians to publicise their views about what is happening in Ukraine although I imagine it is increasingly difficult for people living in Russia to do that. Cameron, what are your future plans for Northern Ireland Opera?

CM: Our major priority is staging Eugene Onegin in September. I am also trying to build the company and to develop a new programme. We also need to secure more government funding – we have been on standstill funding since 2013 – in order to help us develop a new, ambitious and creative programme. We’re looking to perform a chamber piece again at the start of the year and we’ll continue to tour around Northern Ireland with smaller pieces which lend themselves to being more mobile.

RB: Are there any particular pieces which you would like to stage?

CM: The Philip Glass opera, The Juniper Tree worked very well and was well received by the audience. I’m interested in exploring similar repertoire, perhaps by Bernstein, although I haven’t come to any firm views on this.

RB: I love Philip Glass operas and I’m always pleased when companies stage them.

CM: The Fall of the House of Usher is one of my favourite Glass operas.

RB: Yuriy, which future roles are you planning to take on?

CM: In a week’s time I’m starting work on Mozart’s Don Giovanni in Finland. I have been cast in the title role and am looking forward to working on it. After that I will be working on Verdi’s Don Carlos in France and then I will be working with Cameron on Onegin. I really enjoyed my experience of working with Cameron and his creative team on La bohème so it is good to come back and explore new repertoire with them.

RB: Don Giovanni is one of my favourite operas and there have been so many fine performances of the title role.

YY: I was fortunate to be able to spend some time working with Thomas Allen on the role. He is amazing in terms of the insights he brings to the piece and the character. One thing which links Don Giovanni and Onegin is that both the main characters are unsuccessful in love. Don Giovanni doesn’t manage to seduce any of the women in the opera and Onegin is also unable to forge a relationship with Tatiana.

RB: In that sense, they both get their just deserts. Cameron and Yuriy, thank you very much for talking to us.

Robert Beattie