Switzerland Purcell, King Arthur: Soloists, Chorus, Orchestra La Scintilla, Laurence Cummings (conductor), Zürich Opernhaus, Zurich, 3.3.2016. (RP)

Switzerland Purcell, King Arthur: Soloists, Chorus, Orchestra La Scintilla, Laurence Cummings (conductor), Zürich Opernhaus, Zurich, 3.3.2016. (RP)

Purcell, King Arthur

Cast:

King Arthur: Wolfram Koch

Oswald, King of the Saxons: Florian Anderer

Conon, Duke of Cornwall: Jean-Pierre Cornu

Merlin, an English Magician: Corinna Harfouch

Osmond, a Saxon Magician: Annika Meier

Aurelius, Friend to Arthur: Jan Bluthardt

Albanact, Captain of Arthur’s Guards: Werner Eng

Guillamar, Oswald’s Friend: Simon Jensen

Emmeline, Conon’s Daughter: Ruth Rosenfled

Matilda, Her Attendant: Carol Schuler

Philidel, an Airy Spirit: Mélissa Petit

Grimbald, an Earthly Spirit: Hubert Wild

Honour, Cupid, Forest Spirit & Nereid: Deanna Breiwick

Saxon Priest, Philidel’s Spirit, Siren, Shepherdess, Forest Spirit & She: Hamida Kristoffersen

Shepherdess, Sirene & Venus: Anna Stéphany

British Warrior & Shepherd: Mauro Peter

Saxon Priest, Philadel’s Ghost & Forest Spirit: Spencer Lang

Saxon Priest, Philadel’s Ghost & Forest Spirit: Nicholas Scott

Saxon Priest, Pan & He: Andri Björn Robertsson

Phildel’s Ghost & Forest Spirit: Charles Dekeyser

Cold Genius & Aeolus: Nahuel Di Pierro

Forest Spirits: Marie-Sophie Caspar & Susanne Graf-Konold

Production:

Director and Set Design: Herbert Fritsch

Costumes: Victoria Behr

Lighting Design: Franck Evin

Chorus Master: Michael Zlabinger

Dramaturgy: Sabrina Zwach & Beate Breidenbach

There is so much to enjoy in Herbert Fritsch’s imaginative production of Henry Purcell’s King Arthur for the Zurich Opera ̶ the elegant music, the wonderful costumes and the deft staging. Fritsch’s set could not be simpler, a projected mosaic of pink, green, violet and blue, which at times is a wash of red or black, but it imparts a vibrancy and otherworldliness that is evocative of a mythical, magical, pastoral Britain. There is a “but” coming, however, and a big one. Fritsch’s heavy handed, over-the-top, off-color (at times infantile) humor literally drove people away; there were many empty seats after the intermission. That is a pity, as the second half contains some of Purcell’s most sublime music and the creative team’s best work. It deserves to be seen and heard.

King Arthur is a semi-opera in which the principal characters are actors, and the supernatural and pastoral (or inebriated) characters communicate through song. John Dryden’s libretto for the five-act opera centers on the rivalries between the British King Arthur and the Saxon King Oswald, in war and in love, with Arthur emerging as the victor in both.The object of their passion is Emmeline, the blind daughter of Conan. Apart from Arthur, Merlin is the only character from the tales of the Knights of the Round Table to appear; this is not the mythical Camelot of Guinevere and Lancelot.

Fritsch opted to present the songs and choruses in Dryden’s original English, with the spoken dialogue delivered in German from a new translation by German author and dramaturge Sabrina Zwach. Conductor Laurence Cummings writes in the program that by the end of the opera no one notices which language is being used, but that is not the case at all. One does. The elegant and magical is sung in English and the crude, farcical shtick of the kings and their entourages is in German. Was this an intended or unintended consequence of this bilingual approach?

Fritsch clearly looks to Monty Python and Asterix as the leaping-off point for his King Arthur. There is no question that off-color humor, ribaldry and innuendo were part and parcel of 17th-century English theater. It was a legacy handed down from the Ancient Greeks and employed by William Shakespeare, Jonathan Swift and many other authors. Clearly Fritsch articulated his vision well. The actors embraced it whole-heartedly and performed their parts with zeal. It just seemed so forced and coarse. The dialogue was often shouted. And yet again, just how many gaping mouths and protruding tongues can one endure?

Wolfram Koch’s Arthur suffered under the weight of Fritsch’s concept more than any other character. This Arthur was no young, dashing king, but a careworn combatant, making the antics all the more incongruous. When he goes to shake hands with his rival, he sticks his hand down his backside, gives it a good wipe, takes it out and sniffs it. The rustling of his armor became both a musical and dramatic device, but it was so loud and incessant that it was simply annoying. At one point, he walks alone on stage in circles and you just want the noise to stop. When Emmeline removes his armor piece by piece during the final chorus, all I could think was “Thank God, no more of that blasted clamor!”

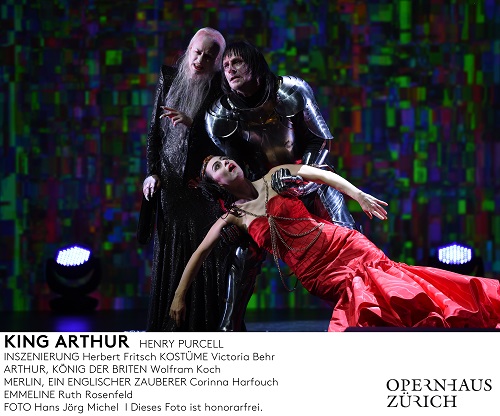

There were also fabulous moments for these mere mortals. Florian Anderer’s Saxon king, although youthful, had a big belly that protruded through his breastplate. He performed a dance in which he shed his attire and evolved into a dashing, young man. It was mesmerizing, perhaps the more so as it was natural and unforced. The female characters fared better than their male counterparts, although they too could wear out their welcome when the comedy became effortful rather than spontaneous. Ruth Rosenfeld in a dramatic red dress as Emmeline, Carol Schuler as her servant Mathilda in an explosion of pink with a fantastic blond hairdo and Annika Meier is menacing black feathers as the sorcerer Osmond were all wonderful actors with rubber faces, physical agility and expert timing.

The theater of Restoration England was renowned for its spectacle and elaborate stagings. There was little of that in this production, save for several cleverly timed entrances employing the below-stage elevators and a bit of mist, but Victoria Behr’s costumes filled the void. If the world of kings and their knights was rough and earthbound, the realm of Dryden’s warriors, shepherds and mythical figures was charming and magical, and yes, spectacular. The effectiveness of the musical ensembles was not merely a function of the costumes, however, as Fritsch staged them with a lightness of touch and whimsy that so simply and effectively captured their essence.

“How blest are the shepherds, how happy their lasses,” led by the pure, sweet tenor of Mauro Peter (who earlier had worn an oversized, red soldier’s costume that was the embodiment of the idealized British Hero), was perhaps my favorite scene. Clad in big white, fluffy tunics and wearing pastel-colored caps that all but covered their heads, the closely clumped-together ensemble swayed in time to the music. It was the flip side of the Monty Python-style humor ̶ playful and light ̶ perfectly tuned to the text and music. Fritsch surely knew the impact this scene would have after the clamor that had preceded it. It was pure bliss.

The most famous music from the opera is the Frost Scene, and here too there was a perfect marriage of costume and staging, abetted by the beautifully sung Cupid of Deanna Breiwick and the tour de force portrayal of the Cold Genius by Nahuel Di Pierro. Cupid was attired in a pink confection with a tight corset and broad panniers with towering, elaborately coifed hair of the same color, while the Cold Genius was robed in white with a headpiece of icicles. Their vocal charms were equal to the visual delights, as was the case with all of the musical scenes, sung by youthful, fresh voices.

After the cast took their bows, the lights were beamed on the orchestra pit, and the audience applauded with real gusto. La Scintilla was excellent and the music that emerged from the pit transcendent. Cummings was the musical assistant for William Christie’s production of King Arthur (which I still recall vividly some twenty years later), and his affinity with, and affection for, Purcell’s music was evident. He is also a good sport, turning to the audience to sing a verse in the finale, but so were the orchestra members. The special sound effects that were heard periodically was them crushing plastic bottles. They were also called upon to stand and witness an attack on the prompter’s box; he apparently survived unscathed despite the onslaught of swords and lances.

The vulgar and the sublime: Fritsch is adept at both. He proved that, but the extremes were too great, and he tries the patience of the audience to almost the breaking point. There is an imaginative, innovative staging of King Arthur buried within the hubris crying to get out, if he would just release it.

Rick Perdian