United States Bizet, Carmen: Soloists, orchestra and chorus of San Francisco Opera / Carlo Montanaro (conductor), War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco. 27.5.2016. (HS)

United States Bizet, Carmen: Soloists, orchestra and chorus of San Francisco Opera / Carlo Montanaro (conductor), War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco. 27.5.2016. (HS)

Bizet, Carmen

CAST:

Carmen: Irene Roberts

Don José: Brian Jagde

Micaëla: Ellie Dehn

Escamillo: Zachary Nelson

Frasquita: Amina Edris

Mercédès: Renée Rapier

Moralès: Edward Nelson

Zuniga: Brad Walker

El Dancairo: Daniel Cilli

El Remendado: Alex Boyer

PRODUCTION:

Production: Calixto Bieito

Revival Director: Joan Anton Rechi

Set Designer: Alfons Flores

Lighting Designer: Gary Marder

Costume Designer: Mercè Paloma

Chorus Director: Ian Robertson

Fight Director: Dave Maier

Carmen makes those running opera companies smile. No matter how much (or little) they might spend on the cast, audiences will fill the seats for Bizet’s familiar music, a wanton anti-heroine and a spectacle of bullfighters, gypsy smugglers, soldiers, a robust chorus and charmingly ragtag children.

San Francisco Opera mounts a Carmen every five years or so, but not since the 1960s, when the likes of Regina Resnik and Grace Bumbry sang the title role and Jon Vickers as the lover Don José, has a cast of truly leading singers taken the key roles. In the 1990s we had Denyce Graves, and a memorable turn by Olga Borodina, but the tenors were not as indelible.

This time around the focus is on Calixto Bieito’s gritty, violent and highly theatrical staging. First seen in Barcelona in 2009, it has since lit up London (at English National Opera), with stops from Ireland to Norway to Palermo. The U.S. debut here is a co-production with Boston Lyric Opera, which mounts it this fall.

The opening-night cast, which alternates with a second set of key role players for a total of 11 performances, delivered vivid acting and consistently well-phrased and correctly executed singing. Musically, mezzo-soprano Irene Roberts voiced a Carmen of silken texture that didn’t quite match the sexual libertine she portrayed. Tenor Brian Jagde’s Don José hit all the notes, even mustered up some delicacy for the finish of “La fleur que tu m’avais jetée,” but not until the final scene did he ramp up the power. Zachary Nelson’s Escamillo phrased with lyricism but fell several watts short of the electric sense of danger the torero should project.

Ellie Dehn’s Micaëla was the most fully realized character. She was no wilting flower singing prettily, but a strong-willed young woman who seemed intent on winning back Don José, not just relaying a message from his mother. Her arias, especially her Act III “C’est les contrabandiers le refuge ordinaire,” married richness of sound with telling phrasing.

Italian conductor Carlo Montanaro, making his company debut, led a refreshingly unsentimental rendering of Bizet’s score. He kept things moving without sacrificing shadings, highlighting moments of orchestral color in Bizet’s music that would have made Berlioz and Ravel proud. The orchestra and chorus responded smartly.

The only missing element was vocal excitement from the cast. Their careful musical execution put the spotlight on the staging.

For decades SFO had repeatedly trotted out Jean-Pierre Ponelle’s likable production. His sliding walls and a colorful tower of rocks for the Gypsy smugglers to climb in Act III did, in its way, create a slightly grittier world than traditional stagings.

Bieito’s ideas, executed here by his long-time assistant Joan-Anton Rechi, cut to the bone. This was no sanitized love affair amid a pageant of Spanish-esque color.

Inspired by the realism of the source material, a harshly framed novella, the Cátalan director moves the action from sunny Seville to a North African outpost of post-Franco Spain. A well-muscled man wearing only underpants and boots circles the army garrison in a first scene dominated by a giant phallic flagpole, signaling both the harshness of the environment and an amped-up level of sexual frankness to come. (The same figure appears naked in a beautifully executed torero-inspired dance to the gentle instrumental introduction to Act III, on a dimly lit stage, beneath a gigantic silhouette of a bull.)

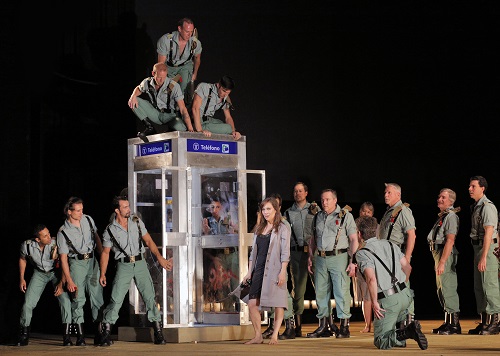

The soldiers manhandle Micaela when she appears. Carmen delivers her first lines from a telephone booth, as if dusting off her most recent lover. She does to sashay around pretending to be sexy. She just goes for what she wants without regret.

The smuggler gang in this staging gives off a stench of nihilism rather than the usual cuteness (all the whole managing the intricate quintet “Nous avons en tête une affaire!” with enviable precision, even while climbing over one of the Mercedes sedans on stage).

Each act begins with something circumscribing the stage. There’s the soldier in Act I. A single sedan rounds the stage in Act II to introduce the smugglers. A fleet of these cars (which the press notes indicate were popular in the Spanish outpost depicted in the 1980s) fills the stage in Act III, and in Act IV the tavern owner Lillas Pastia reappears to chalk a big circle that eventually encloses the final confrontation between José and Carmen. Circumscribing the action sharpens the drama, especially in Carmen’s and José’s final confrontation.

Other theatrical touches are more puzzling. Why does a group of men topple the gigantic silhouette of the bull before Act IV? Why does an eye candy blonde in a red bathing suit sunbathe amidst the crowd before the bullfight in Act IV?

A sense of hard-edge realism did help make the story arc all the more telling. We see Carmen and Don José as misfits, even at their opposite ends of the social environment. José loses his dedication to the army, and Carmen participates with the smugglers only so far as it benefits her. She does more than just dance for José, who realizes only too late that putting in with these dangerous folks was a truly life changing move.

Most productions of Carmen leave us with a much less visceral appreciation what these characters have wrought. This one leads with its gut. Maybe with a few performances under their belts, this cast might do the same.

Harvey Steiman