United Kingdom Monteverdi, Il ritorno d’Ulysse in patria: Cast, The Return of Ulysses Community Ensemble, Thurrock Community Chorus, Orchestra of the Early Opera Company / Christian Curnyn (conductor), Roundhouse, London, 10.1.2018. (CC)

United Kingdom Monteverdi, Il ritorno d’Ulysse in patria: Cast, The Return of Ulysses Community Ensemble, Thurrock Community Chorus, Orchestra of the Early Opera Company / Christian Curnyn (conductor), Roundhouse, London, 10.1.2018. (CC)

Cast:

Ulyssses, Human Frailty – Roderick Williams

Penelope – Christine Rice (acting); Caitlin Hulcup (voice)

Telemachus – Samuel Boden

Eurycleia – Susan Bickley

Melantho, Love – Francesca Chiejina

Amphinomus – Nick Pritchard

Eumaeus – Mark Milhofer

Irus – Stuart Jackson

Peisander – Tai Olney

Antinous, Time – David Shipley

Eurymachus – Andrew Tortise

Fortune, Minerva – Catherine Carby

Boy – Christian Boland Ross

Production:

Director – John Fulljames

Set Designer – Hyemi Shin

Costume Designer – Kimie Nakano

Lighting Designer – Paule Constable

Sound Design – Ian Dearden (Sound Intermedia)

Movement Director – Maxine Braham

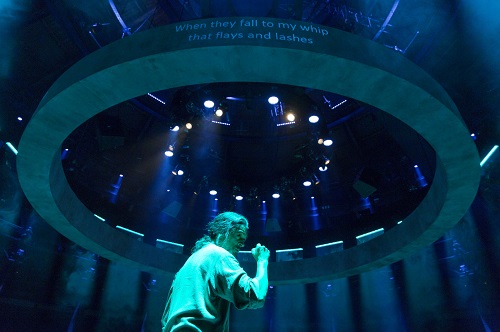

Back in 2015, the Royal Opera collaborated with the Roundhouse in Monteverdi’s Orfeo, reviewed for this site by Mark Berry (click here). Heard here in an English translation by Christopher Cowell, Ulysses offers an intriguing, stimulating and often rewarding experience. The very name ‘Ulysses’ was pronounced throughout with a stress on the second syllable (Ul–Y–sses) as that’s how Monteverdi, obviously, set it and to give it a more English pronunciation would be to over-tinker with the musical line. Hyemi Shin’s staging has the ‘stage’ as a ring that holds at its centre the Orchestra of the Early Opera Company; more intriguingly, both the ring and the orchestra revolve, one clockwise, the other counter-clockwise. The motion of the orchestra reflects perhaps the onward movement of time itself. Elements of the contemporary (in terms of dress) rub shoulders with rather more fanciful elements, like a bunch of white balloons representing so many sheep. Minerva and Telemachus at one point ride round and round the circle, singing radiantly as they do so. Director John Fulljames sets out to make the most of his allocated space, and succeeds.

Characteristions are fascinating, from the chorus, here a community chorus, of Mediterranean refugees kept warm in foil (and fed from the top of the social strata by Penelope, amongst others) to the Michelin-man padding of Stuart Jackson’s properly repellent Irus to the confident young Telemachus, the evident man-totty of the show who gets to take his top off. Despite the dramatic reconciliation of Penelope and Ulysses at the close of the evening, they nevertheless move apart; the reconciliation is far from a happy ending with no questions asked affair.

But there was a singer in the pit, too. Australian singer Caitlin Hulcup, who debuted with the Royal Opera in Arne’s Artaxerxes in 2009, and who apparently learnt the role of Penelope over the weekend preceding this performance. She used a score, but that was really the only indication that the music was not fully in her blood. Vocally indisposed if not physically, Christine Rice (who is due to take over all performances after this one) mimed her way through – quite a challenge if one has one’s back to the pit singer, and indeed sometimes there was the passing impressions of overdubbing going out of sync. Rice, who had to write ‘Ulysses’ over and over again in chalk on the wooden acting circle as if obsessed, gave a dramatically convincing account of the role but it was Caitlin Hulcup’s musicality, her depth of both tone and interpretation, that made one of the most significant impressions of the evening. If Hulcup really did learn the role from scratch in a weekend, this an achievement all the more magnificent; certainly one aches to hear more of her in this repertoire, so stylish was her delivery. Her diction, too, was remarkable.

The title role was taken by the ever-impressive Roderick Williams (more properly Roderick Williams, OBE, after the 2017 Honours List), who owned the part from the very beginning. Williams seems to embrace role he takes on, from van der Aa to Mozart; of course Williams’s singing career began with the vocal group I Fagiolini (a group that has recently released a related CD on Decca, Monteverdi: The Other Vespers). His disguise was brilliantly done; he lived the experience: from the competition to string the bow (well, and amusingly, done by the suitors as well here) to the revelation of his identity, his every movement, his every utterance, was gripping.

The discovery of the evening, and the another ‘significant impression’, was Francesca Chiejina’s simply delicious assumption of Melantho, the lover of Eurymachus (a fine reading by Andrew Tortise). A Jette Parker Artist, Chiejina acts brilliantly, has phenomenal stage presence, and a voice of gold; all were evident from her assumption of the part of Love at the very outset of the evening. Eminently believable at each and every juncture, always completely focused on the moment dramatically, she is set, I predict, to be a major voice (pardon the pun) in coming years. She also is blessed by not inconsiderable beauty. Together with the enthusiastic Tortise, the two made for a fresh and believable pair.

Catherine Carby was a magnificent Minerva, intimidating in her breastplate (implications of Boudica, perhaps!), her steely voice every inch the reflection of her attire. Penelope’s maid, Eurycleia, was taken with practised confidence by the experienced Susan Bickley, while Stuart Jackson’s fine portrayal of Irus properly climaxed with his late monologue. The headphone-toting Telemachus, Samuel Boden, was striking both visually and vocally.

The suitors, Nick Pritchard, David Shipley and the astonishing US countertenor Tai Oney, of whom I for one am itching to hear more, made a fine fist of their roles, each with their own individual characters and, indeed, character faults. Mark Milhofer was a brilliantly characterful and vocally sound shepherd, Eumeaus.

The pit band was in brilliant form. The long opera demands massive concentration from its participants, and the standard never flagged. Bright cornets in particular added a sense of colour; Curnyn kept the action moving. The credit for SoundIntermedia is for the voice amplification, generally fine but occasionally too obvious and prominent.

A rewarding experience, without doubt; not an unqualified success, but so worth it for Williams’s Ulysses.

Colin Clarke