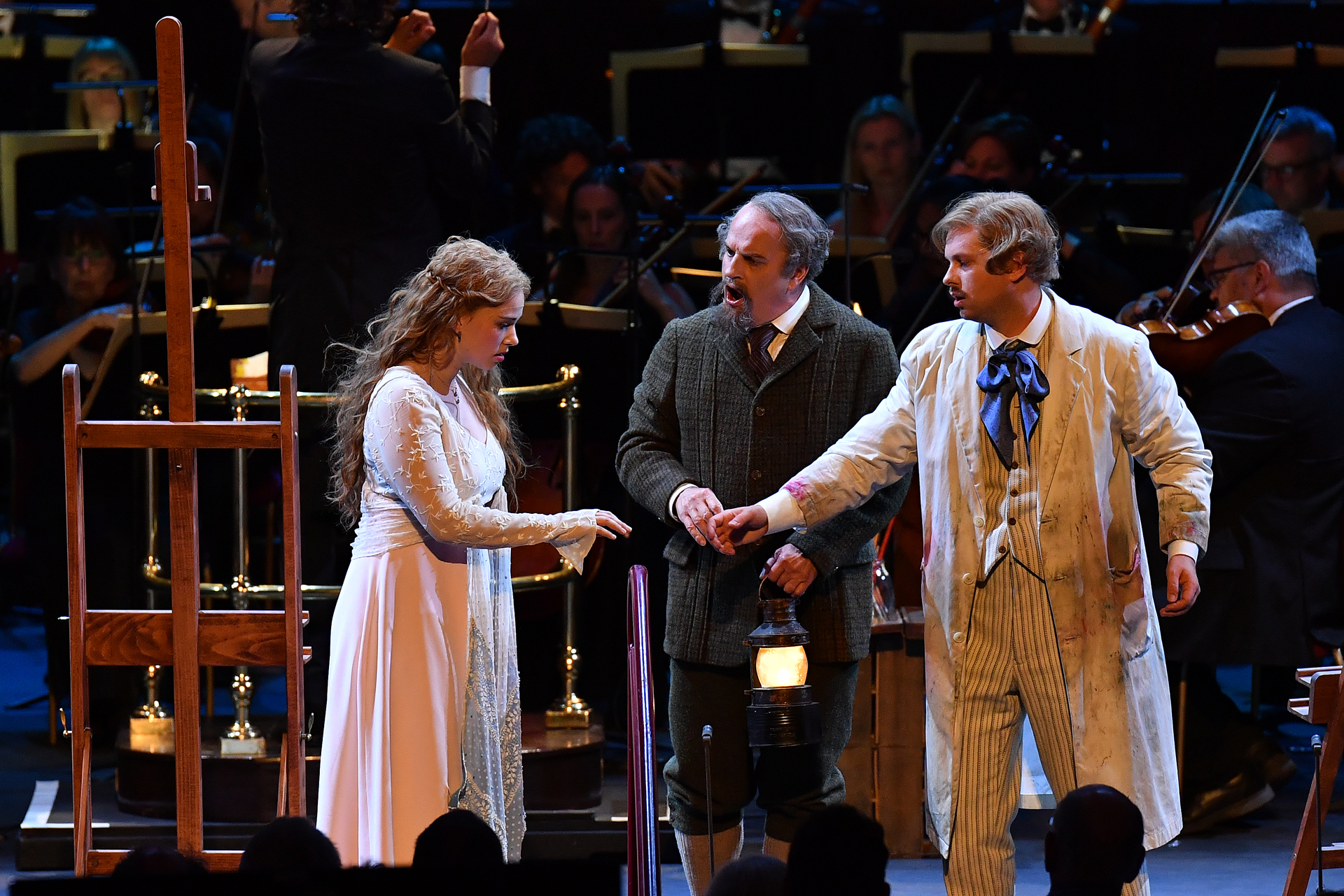

United Kingdom Prom 5 – Debussy: Soloists, The Glyndebourne Chorus, London Philharmonic Orchestra / Robin Ticciati (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, 17.7.2018. (JPr)

United Kingdom Prom 5 – Debussy: Soloists, The Glyndebourne Chorus, London Philharmonic Orchestra / Robin Ticciati (conductor). Royal Albert Hall, London, 17.7.2018. (JPr)

(c) BBC/Chris Christodoulou

Debussy – Pelléas et Mélisande

Cast included:

Christopher Purves – Golaud

Christina Gansch – Mélisande

John Chest – Pelléas

Karen Cargill – Geneviève

Brindley Sherratt – Arkel

John Chest – Pelléas

Chloé Briot – Yniold

Michael Mofidian – Doctor

Michael Wallace – Shepherd

Semi-staging by Sinéad O’Neill based on the current Glyndebourne production by Stefan Herheim.

I don’t know why my thoughts have turned to Shakespeare but a rewrite of a couple of his most famous lines came to mind when at my first Prom of this season: ‘And gentlemen [and gentlewomen] in England now a-bed shall think themselves lucky they were not here’ especially if they were music lovers listening to the broadcast on BBC Radio 3!

This was a strange, yet fascinating, evening. Undoubtedly the best-ever semi-staging of an opera at the Proms. This was helped – in no small part- by the recent realisation that surtitles can work in the Royal Albert Hall and no longer do forests have to be cut down to print weighty tomes with English translations. However, Stefan Herheim’s production of the opera at Glyndebourne – the basis for this semi-staging – seems to have puzzled many commentators including Seen and Heard’s own Colin Clarke (review click here). He refers to how ‘Symbols layer upon an already symbol-drenched score’ though suggests ‘a rematch might bring forth hidden depths’.

Claude Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande has eluded any great popular acceptance. Indeed, this seems to continue to this day as the Royal Albert Hall was far from full and even emptier after the interval when those scratching their heads at what they were seeing decided to probably listen to the rest thanks to BBC iPlayer. Most operagoers who visit the Proms are unlikely to be familiar with such a highly-intellectualised and dramaturgically-driven approach to staging an opera that is Herheim’s forte. This is something I know well from Bayreuth and elsewhere but might have baffled many among the Proms’ audience of classical music aficionados, those going to the Proms because it is the Proms and random visitors to London with a night off and needing to see something.

Debussy was a passionate Wagnerian who – like many of us – underwent repeated ‘pilgrimages’ to Bayreuth, whilst remaining – also like many of us – anything but uncritical. Whilst seeking to emulate the German master – although in a French manner – Debussy was clearly under the spell of Tristan und Isolde and Parsifal when he wrote his 1902 masterpiece. The libretto for his only completed opera was a five-act prose drama by Maurice Maeterlinck, a work inherently rife with that aforementioned symbolism, even if it is not entirely clear exactly what the original symbols represent here and there. Thoughts on this are best left to another occasion or to others. What is without doubt is that Debussy unravels his simple, sombre and downbeat plot much too slowly – across what are more like five extended scenes – to occasionally test the listener’s patience.

The widower Golaud, father of the young Yniold and son of old King Arkel d’Allemonde is lost in the woods. He stumbles across a girl sobbing by a pond in which she has lost her golden crown, but Golaud does not find out much more about her except that she had, apparently, suffered abuse in the past. Golaud soon marries her but she seems far more interested in his younger half-brother, Pelléas. The relationship between stepbrother and his new wife seems entirely chaste but it eventually drives Golaud to fratricide. We are supposed to see Mélisande throw her long golden tresses from a tower for Pelléas to caress erotically and it is very late in the opera when they actually admit their feelings for each other in a love duet in Act IV that is inspired by the one Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde sing. Mélisande dies soon after giving birth to a daughter, the tortured Golaud is left literally holding the baby … but whose child is it?

Herheim’s original setting represents the Organ Room at Glyndebourne and apparently parallels that used by David Hare’s recent origin story seen in the West End (review click here). In Sinéad O’Neill’s admirably detailed semi-staging what we get looks like part Eugene Onegin and part the forthcoming Downton Abbey film. In addition to the leading characters; housekeepers, maids, butlers and valets were often bustling around the occasionally cluttered performing space in front of the orchestra and the Royal Albert Hall’s own Grand Organ. There was a trio of empty easels at one point, a well-laid dinner table sometime later and of course there were some chairs which of course must be thrown over.

Yniold is always lurking around sketching and paintings and painters seem important to Herheim as if those we are seeing are part of a dysfunctional pre-Raphaelite brotherhood which Mélisande has intruded into. In Golaud’s Act III scene with Yniold his sexual jealousy reaches such a climax that he appears to rape Yniold in his lust for Mélisande whose appearance the ‘boy’ takes on at that point. There are lots of hand gestures with eyes being frequently covered over – there are none so blind as those who will not see, perhaps? Golaud is hiding in plain sight during the love duet and he blinds Pelléas and later Mélisande. Debussy’s Shepherd becomes a priest (Michael Wallace) who presumably is the embodiment of the Lamb of God? Although I was having to wonder too much about what Herheim wanted us to think the end was very affecting as the shade of the dead Pelléas’s reappears to lead the transfigured Mélisande away after her liebestod.

The London Philharmonic Orchestra added immensely to what enjoyment there was from this Pelléas et Mélisande. Whilst Robin Ticcati’s leisurely approach to the music seemed to stop and start too much but still had the ebb and flow that, I suspect, Debussy intended to achieve with writing somewhat dependent on the natural speech rhythms of the French language. It was admirable in that in the notoriously difficult acoustics of the Royal Albert Hall that Ticciati was sufficiently sensitive to his cast that almost every syllable of Maeterlinck’s text could be understood.

Once Mélisande arrives at Arkel’s castle and sets her sights on Pelléas her mysterious past – as the girl found weeping beside a forest well – is quickly forgotten and she appears all too knowing. Christina Gansch’s Mélisande becomes a manipulative, independent spirit, clearly aware of her disruptive effect on the decaying dynasty into which she has married. Gansch sang very well throughout and highlights of her performance were her expression of love for Pelléas and her sad farewell to the world at the ends of Acts IV and V

I didn’t experience the greatest amount of chemistry between Gansch and John Chest’s sappily romantic, possibly slightly effete, Pelléas, regardless of how much ardour he tried to show. Having the role sung by a tenor – as is sometimes the case – would have allowed for a more even distribution of voices among the singers. Chest’s voice was not that different in timbre to Christopher Purves’s deeply troubled Golaud who was clearly in need of anger management counselling were there any at the time Herheim has set the opera. Obviously a bit of a violent bully, this Golaud was quick to lose his rag when faced with a distraught Mélisande who had lost her ring or when catching the lovers in a compromising situation. When it all became too much he completely loses it during the opening scene of Act IV, but this would have been even more frightening if Purves’s Golaud had shown just a little more restraint earlier. I suspect – despite singing strongly throughout – the coarser edge Purves brought to his baritone voice was all in the service of this characterisation.

The minor roles were admirably taken by Brindley Sherratt bringing his usual imposing gravitas to paterfamilias Arkel; the always reliable Karen Cargill was luxury casting as Geneviève – making me wish her role was much bigger – and there was some wonderfully assured idiomatic singing from the boyish Chloé Briot as Yniold, Golaud’s increasingly traumatised son.

Finally, the printed programme could have done more to prepare the audience in the Royal Albert Hall for what they would see, as well as, hear but it took long enough to get surtitles, so I am not expecting any more miracles soon.

Jim Pritchard

For more about what is at the 2018 BBC Proms click here.