Germany Wagner, Siegfried: Soloists, Bayreuth Festival Orchestra / Marek Janowski (conductor). 2016 performance from the Bayreuth Festspielhaus and reviewed when streamed for 48 hours on DG Stage. (CC)

Germany Wagner, Siegfried: Soloists, Bayreuth Festival Orchestra / Marek Janowski (conductor). 2016 performance from the Bayreuth Festspielhaus and reviewed when streamed for 48 hours on DG Stage. (CC)

Production:

Stage Director – Frank Castorf

Stage Design – Aleksandar Denić

Costumes – Adriana Braga Peretzki

Lighting – Rainer Casper

Video – Andreas Deinert, Jens Crull

Cast:

Siegfried – Stefan Vinke

Mime – Andreas Conrad

Der Wanderer – John Lundgren

Alberich – Albert Dohmen

Fafner – Karl-Heinz Lehner

Erda – Nadine Weissmann

Brünnhilde – Catherine Foster

Waldvogel – Ana Durlowski

This is the first of the Janowski Ring cycle to be advertised by DG Stage as ‘+ Artist Commentary’ but it seems to be exactly the same talk.

We shift venue again, this time twice in one music-drama: firstly, a reimagined Mount Rushmore and then to Berlin’s Alexanderplatz (reminding us of the old East/West Germany division). At the outset, there are four Mount Rushmore-like figures above the stage overlooking a metal shack (the latter a recurrent piece of this Ring‘s furniture). Here, though, we see Marx, Lenin, Stalin, and Chairman Mao, four fathers of Communism. While oil – and therefore material greed – is the underlying theme of this Ring that itself calls itself ‘post-dramatic’ and is therefore riven with free associations – here in the plateau of Siegfried we are in something of a liminal space, a no-man’s land. The staging does get more complex as the music-dramas proceed, with the rotating set (and use of film, either on large, ‘cinema’ screens, or for example, on a small television in a kebab hut) enabling rapid moves between one setting and another.

Janowski spoke of his admiration for Siegfried, and it comes across in arguably his finest performance of this 2016 Ring. Once again, the ear is continually guided towards the orchestra. The tuba player in particular is stunning as is the great ‘Sword motif’ statement. He is joined by the Mime of Andreas Conrad, who keeps chained ‘slave’, a mute, bespectacled subhuman who will recur in various guises, even to snort drugs in the Götterdämmerung, while in Siegfried he even acts as a human set of bellows. (Wagner’s admiration of mime – lower-case ‘m’ – has been posited, perhaps in reaction to the 1877 production of Rip Van Winkle Wagner saw in London in 1877, starring the American actor – known for his mime – Joseph Jefferson).

Stefan Vinke as Siegfried has a fabulously free upper range, strong and unstoppable. His Mime in the glorious opening scene is Andreas Conrad, sloppily dressed, including a vest that has most definitely seen better days. No monochrome Mime this: how fabulously Conrad puts his voice into neutral for ‘Fafner, der Wilde Wurm’. Both Vinke and Conrad cope fabulously with rapid-fire declamation: Janowski’s speed can be very rapid – headlong, even.

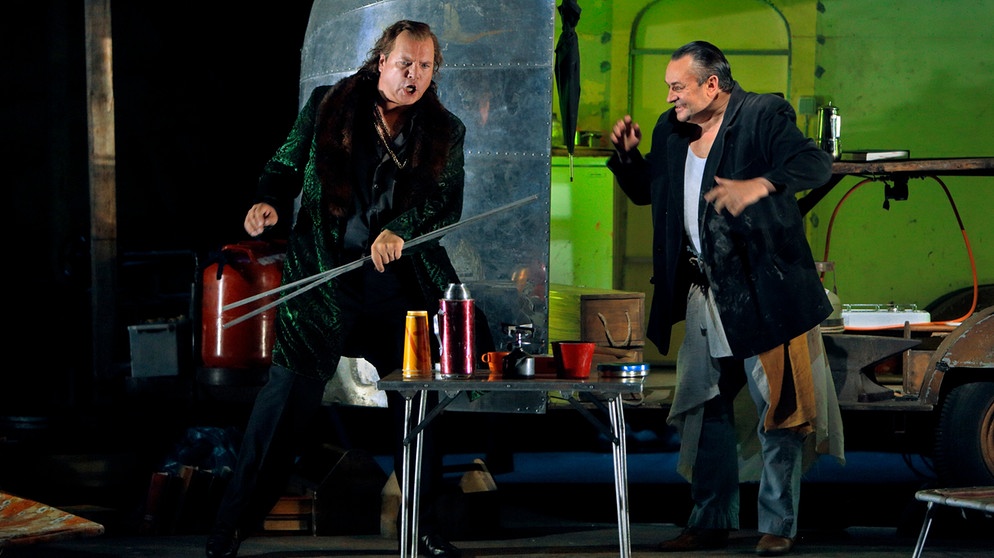

The imposing Wanderer finds John Lundgren in fine voice, bringing authority, and, ironically, more authority than when his in ‘God’/Wotan guise. His ‘schmiedet Nothung neu’ is a highpoint of his reading, commanding, solid. The contrast between the Wanderer’s intonings on a single line and Mime’s far more angular line are strongly drawn. This is matched by Vinke’s Forging Song – this is a super-confident Siegfried, all sparkly waistcoat, open shirt, and bling. He has guns at his disposal, not just a sword; and, important for us, a (pardon the pun) ringing first statement of ‘Nothung!’. The mute headbangs along to the Forging Song, the orchestra absolutely ecstatic.

Act II – deep night, in front of the metal van – brings Albert Dohmen, still in fabulous form, as Alberich, his ‘Im Wald und Nacht’ wondrous; the Wanderer appears, tattooed, in see-through top with a Celtic Cross design on it. And, as far as I can see, eyeliner. Fafner is seen having a ball with his own personal harem.

As orchestral transitions go, Janowski’s into the second scene is faultless. Of course, there is no lime tree under which Siegfried should sit. Here we are in a very German setting; our Woodbird is almost a butterfly-creature, strange and fabulous. Plastic waste plays a part, a modern woe – Siegfried prods it and the oboist plays out of tune. Inevitably, this being Bayreuth, there is a fantastic horn player for the solos (perhaps the horn’s final top C is squeaked out a little); but dramatically, this is gripping. Sexual interactions between Siegfried and the Woodbird may be there to shock, but by now they are no more surprising than the machine gun violence of Fafner’s death. Ana Durlowski’s Woodbird is beautifully agile, vocally.

It is in the final act that John Lundgren’s Wanderer comes into its own, film effectively used as he calls Erda (who, fabulous in furs, exudes confidence). Wanderer and Erda share a meal al fresco outside the German Post Office, the waiter none other than our mime artist. It’s certainly a sexually charged encounter, with Wotan’s hand spending a long time on Erda’s breast (it does rather feel like he’s abandoned it there while he thinks about something else, though) and there’s a BJ for dessert. Act III moves between Alexanderplatz and Rushmore; we also return to the sleeping Brünnhilde, now aslumber in golden sheets. At least there is no audience laugh at ‘Das ist kein Mann’, but when he is supposed to faint on her breast, Siegfried is actually halfway up a flight of stairs. Musically, however, this final scene is a triumph. Vinke has plenty left in reserve, clearly, and Catherine Foster’s voice gleams as Brünnhilde greets the sun.

One of the most controversial aspects of the production was the appearance of animatronic crocodiles (one of which was possibly malfunctioning at this performance, but maybe not: who knows?) in the final scene. One of the things they get up to is to feed on the Woodbird, but perhaps it was a mistake to have them upstage while Siegfried and Brünnhilde are downstage (possibly less disturbing live as the camera shot emphasises the stage placement – although given we are talking about a machine crocodile with malfunctioning mastication, you’re going to notice it wherever it is). The crocs are certainly distracting, which is more than unfortunate given the glorious climatic nature of the music.

The boos from the audience are immediate and mixed in with a sort of indeterminate howling, both of which change instantaneously to rapturous cheers for Vinke and Foster on their arrival for a bow.

Food for thought, definitely. The orchestra is triumphant, the singers excellent.

Colin Clarke

For what is on DG Stage click here.