United Kingdom Debussy, Ravel, Chopin – Hao Zi Yoh (piano): Recital livestreamed from St Mary’s Perivale, Ealing, London, 8.3.2021. (JB)

United Kingdom Debussy, Ravel, Chopin – Hao Zi Yoh (piano): Recital livestreamed from St Mary’s Perivale, Ealing, London, 8.3.2021. (JB)

Debussy – Golliwog’s Cakewalk; La Cathedrale engloutie

Ravel – Jeux d’eau; Valses nobles et sentimentales

Chopin – Mazurkas Op.59, Nos. 1-3; Etudes Op.10, Nos. 4 and 7; Ballade No.4 in F minor Op.52

Just imagine in our age of political correctness, playing a rumbustious piece of music (now controversially) titled Golliwog’s Cakewalk. I can, however, see a wry smile passing across the face of Claude Debussy, who wrote it for the education of his only, most beloved, very young, daughter, Claude-Emma or ‘Chouchou’, as he affectionately called her. He also wrote another ragtime piece for Chouchou called The Little Nigar: his spelling, which might not have been enough to exonerate it from today’s all-embracing woke sensibilities.

Wit is all too frequently a difficult attribute to recognise in music, let alone to deliver. Hao Zi Yoh gives both. (Fanny Waterman, recognising my sense of humour, once gave me Little Nigar to learn as an encore.) This was the opening of Hao Zi’s challenging recital at St Mary’s Perivale. Don’t take my word for it. Go to their website (click here) and enjoy it for yourselves. There is more than a touch of mischief in this music as well as borrowings from ragtime. (Warning: I shall be reporting on Mozart’s very different, but no less remarkable wit in an upcoming piece.)

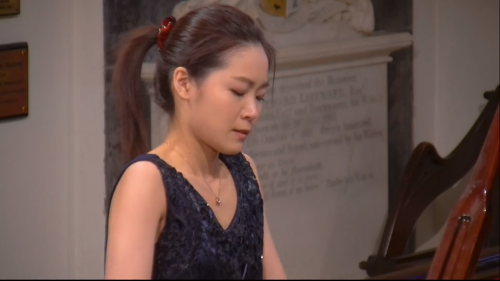

For those who don’t know, Hao Zi is a beautiful slender young woman from Malaysia and visiting tutor of piano at Imperial College, from where I hope to report on a seminar. I have already understood that her tutoring would be readily comprehensible to the scientists: precision is the key to the magic of musical languages. Somewhat like being a ballerina: if you are beautiful to begin with, half the work (Lindsay Kemp used to say three-quarters) has been done for you.

You can see why Debussy disapproved of his music being considered impressionist. There are ways it does not fit that bill. While on the other hand, there are ways that it does. Debussy admitted great influence from J. M. W. Turner’s landscapes and seascapes. While his music is always magnetically drawn towards tonal centres, it also challenges these centres: hanging in the air with a mysterious weightlessness, maybe best summarises it. Sometimes it comes crashing to earth, as in the Golliwog’s Cakewalk, itself a parody of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde prelude which the composer declared the most moving piece of music he had ever heard. (You may need to listen again to hear how Cakewalk both stokes and shadows Wagner’s solemnly haunting theme.) Hao Zi has a distinctly no-nonsense approach to these bars. You may laugh. But it will be a respectful laugh. No hint of mockery.

Debussy gets really serious when it comes to La Cathedrale engloutie (The sunken cathedral). This might have been a Turner inspiration too. It wasn’t. The mythical cathedral rises unexpectedly from the deep, also at unexpected moments. As it arises, it returns, leaving only its mists. The tempo is slow, uncertain but in its own way, decisive. Some nifty pedal work is needed: echoes and suggestions of sounds which cannot be arrived at. Hao Zi brings to it balances of profound beauty. This beauty is achieved by what Keats would have called negative capability: foregrounding your knowledge with evidence of aspects you know you cannot foreground.

Some readers may be surprised to know that Debussy held Chopin as the greatest of them all. This on account of the Polish-Frenchman – mother Polish and father French – expressing his creativity exclusively through the piano. Soon after his twenty-first birthday, Chopin transferred to Paris, making his living through the intimacy of piano recitals in the salons of the wealthy, where he found students as well as influential – in every sense of the word – audiences.

There is a tendency to think of Debussy and Ravel in the same breath. In many respects that is a mistake. Both men were loners to a high degree. Debussy was born poor and struggled to make ends meet. Ravel was born rich and became richer. Toward the end of his life – following the final success of his only finished opera Pelléas et Mélisande – Debussy was able to say he had triumphed financially. Although undoubtedly influenced by Wagner’s Parsifal (both operas are atheist struggles to find a meaningful religion) Pelléas remains a unique accomplishment, more popular with critics than audiences. Mary Garden, the Scottish soprano, who had a light, ‘open-ended’ voice which triumphed as Mélisande but had poor French diction and declared Debussy a boor and a bully. Another light soprano from what was then known as Great Britain, Maggie Teyte, took over the role, and was bilingual; though Teyte also found Debussy a bully who had a disregard for everyone, including himself, with the possible exception of his only daughter.

Because of family money, Ravel was able to float through life with ease and charm, both qualities audible in his music. Ralph Vaughan Williams, going through a personal crisis, approached Ravel for composition lessons. Ravel took one look at RVW’s manuscripts and said, If I could write music like this, I would not be coming to me for lessons. It worked. RVW returned home and produced some of his best work, garnering great acclaim from both critics and the public.

But Ravel had a skeleton in the cupboard. At a champagne lunch in the 1970s in Paris, the Director of Éditions Durand, the music publishers who were responsible for most of Ravel’s many successes, told me that the composer’s brother and sisters were excluded from his Will: all the royalties went to the butcher’s boy with whom the composer had been having a secret affair. Ravel’s Jeux d’eau is a 1902 exploration of the pleasures of the river god. It was premiered by Fauré, with whom Ravel was studying, and drew great applause. Martha Argerich recorded it in 1962 where the delightful playfulness is to the fore. As indeed it was with Hao Zi’s performance. The music moves always toward E major but is often ‘thwarted’ on its way there.

Ravel always found the waltz fascinating. His suite of eight of them premiered in 1911 with a quotation from Henry Régnier, which translates as the delightful and ever-novel pleasure of a useless occupation. That sounds like John Cage before his time. Hao Zi certainly has fun with these pieces, as slight and slender as herself. And so do her audience in consequence. There is very much the feel of the Music Hall’s all together now. When Ravel is present can the togetherness ever be far behind?

Hao Zi has played some of her Chopin pieces in a previous recital which I reviewed. Is there anything to add to what I have said? The answer is yes. And it comes with the word nuance. Her ear is sharp, and rethinking this music is the very soul of her art.

This is most obvious in the two Etudes. All nineteenth-century pianist composers wrote studies for the instrument. But in most cases studies are for practising purposes only and to ensure workmanlike technique. With Liszt, the Etude became an entertainment with an ‘anything you can write I can write with more challenges’ objective. Chopin adds in poetry to the challenge. Remember, the handsome young Polish virtuoso was entertaining the Paris literati and aristocracy. Some became pupils. The maestro showed them that ‘Studies’ could be anything but dull. Add into this that the little lad was dying of consumption, yet he avoids self-pity; but by going into an instinctive poetic mode, reaches the back row of his audiences. And Hao Zi has absorbed all this and delivers every piece as growing out of the moment. To put this in Artur Rubinstein terms, she would not know what she was going to play until she had played it. On this occasion, the intimacy of the medieval twelfth-century church helped. And more so because it was empty. That is double credit for all of us listening in to this magic.

The three Op.59 mazurkas are another matter. These traditional Polish dances clearly speak their native language. Especially No.3, which is more properly called an Oberek. This is a folk dance where all the focus is on the male’s leaps and bounds with the female gently encouraging her partner. Chopin wrote more mazurkas than any other form. Some of them are so brief that if you blink, you miss them. But for Chopin these gasps of music were sketches to be incorporated into longer works.

No one will ever perform these pieces like Rubinstein. A genius at home in his own musical language. Between 1938 and 1939 he recorded all 59 mazurkas. They have been reissued on Brilliant Classics. What can sound awkward under most fingers – as stern rhythms seem interrupted (ties across bar lines are common) – Rubinstein plays with a matter-of-factness that gives a beautiful, understated calm to what can easily come out as turbulence. Our Malaysian friend, however, also has a rather good line in matter-of-factness. Listen for it.

Chopin’s Op.52 F minor Ballade is another story again. John Ogden used to say that the Ballade is so richly complex that it is unperformable. All the same, you can hear Ogden’s attempt at performance on YouTube. And pretty awe-inspiring it is. He treads with awesome care and takes us through a musical adventure unequalled in recording history. I find myself holding my breath as he searches out Chopin’s musical sense. Nothing will probably ever match this. In comparison, all other performances I have heard fall dramatically short of the mark.

Still, Hao Zi has something to tell us about this Ballade: its yearning, where cantabile passages cry out with pain, which crescendos into wrath before it melts into quiet prayer. Quite a musical voyage. I cannot help thinking that Ogden would have applauded her musicianship if he were still with us. It is not as incisive as his own performance but surely one he would have found interesting.

Please got to the St Mary’s website to see other upcoming recitals. All supported by volunteer experts. Perivale has the advantage of being on the doorstep of the BBC recording studios and two gentlemen in particular who operate from the church’s tower to bring us the finest recordings you will hear anywhere. Lucky young musicians. And lucky us. Dr Hugh Mather – whose brainchild this project is – gives a brief history of the enterprise in another part of Seen and Heard (click here).

Jack Buckley