Germany Richard Strauss, Capriccio: Soloists, Men’s Chorus of the Dresden State Opera, Staatskapelle Dresden / Christian Thielemann (conductor). Recorded (directed by Tiziano Mancini) at the Semperoper Dresden on 8.5.2021 and streamed from 22.5.2021. (JPr)

Germany Richard Strauss, Capriccio: Soloists, Men’s Chorus of the Dresden State Opera, Staatskapelle Dresden / Christian Thielemann (conductor). Recorded (directed by Tiziano Mancini) at the Semperoper Dresden on 8.5.2021 and streamed from 22.5.2021. (JPr)

Production:

Staging – Jens-Daniel Herzog

Set design – Mathis Neidhardt

Costume design – Sibylle Gädeke

Lighting design – Fabio Antoci

Choreography – Michael Schmieder, Ramses Sigl

Dramaturgy – Johann Casimir Eule

Chorus director – André Kellinghaus

Cast included:

The Countess – Camilla Nylund

The Count – Christoph Pohl

Flamand – Daniel Behle

Olivier – Nikolay Borchev

La Roche – Georg Zeppenfeld

Clairon – Christa Mayer

Monsieur Taupe – Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke

Italian singers – Beomjin Kim, Tuuli Takala

The Major-domo – Torben Jürgens

Capriccio is an opera that is all about the role of words and music in opera and also stirs a debate on whether the beliefs and actions of the composer can be divorced from the works they produce. The conductor Arturo Toscanini once declared, ‘To Richard Strauss, the composer, I take off my hat, to Richard Strauss, the man, I put it on again.’ Should – or shouldn’t we – allow what we know about an artist to affect the way we view their creations? In brief, Strauss (with his Jewish ancestry) became president of Hitler’s Reichsmusikkammer (Reich Music Chamber) in 1933 and much of his conduct – acquiescence? – during the Third Reich was apparently to protect his beloved Jewish daughter-in-law and grandchildren from persecution and being sent to concentration camps. Perhaps something for discussion at another time and place, however, whereas the debate around Wagner’s anti-Semitism never goes away, Strauss with much more irrefutable ties to Hitler has been largely exonerated and we continue to venerate his musical and dramatic genius.

Seven years before his death in 1949, Capriccio found Strauss in a reflective career-end mood and it evokes a little of Der Rosenkavalier’s atmosphere yet is actually far removed from that world. Composed at a time when British bombs were falling in Germany and there was state-sponsored murder going on around him, it begs the question, how – or why – does Strauss to come up with this ‘A Conversation Piece for Music’ as his final opera? It seems you can take Capriccio out of the eighteenth century where the debate about the nature of opera originated (as productions including this new Dresden can do), but it is difficult to completely divorce the eighteenth century from the opera itself. Capriccio was inspired by a libretto from that time Prima la musica, e poi le parole (First the Music, and Then the Words) by Abbé Giovanni Battista Casti, which was set to music by Antonio Salieri in 1786. The choice between music and words is embodied by the composer Flamand and the poet Olivier, each of whom is infatuated with a young widow, the Countess Madeleine.

Over two and a half hours the theoretical debate rages on, nominally in a château near Paris in the latter half of the eighteenth century, between Flamand, Olivier, the Countess, and her brother, the Count, who is captivated by a famous actress, Clarion, as well as, La Roche, a theatre director and a prompter (Monsieur Taupe) of all people. It is all very wordy and characterised by several musical in-jokes which makes Capriccio an acquired taste, I have now seen it once, glad I did but will not rush to see and hear it again.

Points made can seem complex or moot and regardless are often difficult to follow even with a complete understanding of the German or a good translation. Along the way there is much name-dropping of illustrious musical figures, such as, Gluck, Corneille, Lully, Rameau, Piccinni, Goldoni, Couperin, all contemporary to the period in which Capriccio is set. (There are also references in the score to Strauss’s earlier compositions.) It is left to the Countess to resolve the primacy issue about words or music; a decision which would suggest whether it will Olivier or Flamand who will be her next husband. At the end, neither the either-or matter of the Countess’s heart nor that of the theorising about opera is resolved.

Capriccio therefore is an opera which seems to be handcuffed in its own time and place. Jens-Daniel Herzog has been director of the Staatstheaters Nürnberg since 2018 and while the place remains the same – here more Schloss than château – give or take the sojourn to backstage at a theatre, the time is brought forward to Germany during the second world war (the time Capriccio was written) with suitable costumes from Sibylle Gädeke apart from the Countess who will appear near the end of the opera as if she were from the late-eighteenth century. Mathis Neidhardt’s revolving set features a wood-panelled salon, plush enough though rather a little austere. There were bullet holes in the distressed outer brick wall and LSR with an arrow painted on it and these initials stood for Luftschutzraum (air raid shelter). Flamand enters wearing a plain army uniform with a kit bag as if off to the front.

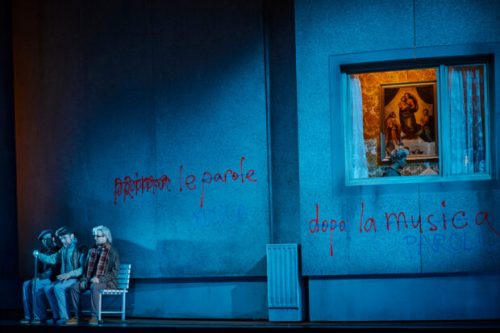

The opera starts with the sublime string sextet and we see the elderly La Roche sitting in front of a wall and falling, as expected, asleep. He is joined by two further senior citizens on his bench who we appreciate are Flamand and Olivier and they soon spray-paint ‘Prima le parole, dopo la musica’ and ‘Prima la musica, dopo le parole’. It is clear the dispute has been going on for decades. Behind a smallish window an elderly woman is watching a black and white film on TV of the Countess singing in a performance of Capriccio whilst we realise it is her older self who thumbs through the score.

Olivier has written a new play as a tribute (Huldigungsfestspiel) for the Countess’s imminent birthday, which La Roche will direct and the Count and Clairon will perform in. La Roche, Olivier and Flamand proceed to a rehearsal. The Count gesticulates theatrically during the read-through of Olivier’s play and I am certain we are supposed to think about Hitler’s oratory. It ends with a love sonnet that Olivier purloins to set to music. Soon the Countess is having to fight off the attentions of Olivier before being serenaded by Flamand at the harpsichord and overcome by his ardour. When all those in the play appear in traditional eighteenth-century garb, complete with frock coats and powdered wigs, there is a sense of relief that for most of this Capriccio the men are in clothes appropriate for the 1940s!

Eventually, we see all concerned entertained by two Italians singers and eight dancers; the singers are costumed as Harlequin and Columbine and one lone female dancer in a loose pink shift dress starts with some contemporary moves. She is then joined by seven bewigged and ostrich-feathered dancers and with a sense of ‘if you can’t beat them, join them’ she reverts to a more courtly style of dancing. The Count soon makes the memorable assertion ‘Eine Oper ist ein absurdes Ding’ (‘Opera is an absurd thing’) – a discussion which rages to this very day! – and soon the backstage reception descends into chaos. The character of La Roche was apparently inspired by great Austrian theatre and film director Max Reinhardt and he propounds – at length – his own thoughts. He defends the theatre of the past and his achievements in preserving its artistic traditions and you cannot fail to hear the ‘voice’ of Strauss here. Eventually the Count suggests the idea of an opera about the events of their afternoon, therefore showing the real people whose stories La Roche wanted from Flamand and Olivier.

Fast forward to the great final scene when the Countess wrestles with her dilemma and wonders if she can supply an ending which is not trivial. Herzog has her confronting her older self (rather than her reflection in the mirror) as she sings ‘I want an answer and not your scrutinizing look! You are silent? O, Madeleine, Madeleine! Do you want to burn between two fires?’ before – after she is told dinner is served – bequeathing her Capriccio score to the older Countess and exiting at the back of the stage with ‘the chicken or the egg’ quandary unanswered.

The Countess is at the heart of the opera and Camilla Nylund was an elegant and refined presence and given a timeless look initially. Her voice is now quite big – as heard through loudspeakers of course – as befits a singer soon to debut as Brünnhilde. Perhaps the ideal Countess needs a voice with a more delicate, lighter quality and a greater purity of tone; yet Nylund got better and better and from the quarrelling octet until her deeply affecting last moments there was some beautifully phrased singing, sublime pianissimos and super colouring of her words.

The rest of the cast was uniformly excellent. Georg Zeppenfeld’s rendition of La Roche’s monologue after his planned birthday entertainment of the ‘Birth of Pallas Athene’ and ‘Fall of Carthage’ is derided was a tour de force as he expounded with inordinate conviction about what constitutes a good production. Zeppenfeld seems everyway these days and was recently Gurnemanz in Vienna and Hunding in Milan and everything Zeppenfeld sings is notable for his fine diction and the expressivity of his robust bass voice that commanded the listener’s attention during his lengthy tirade.

Tenor Daniel Behle was an ardent, impassioned Flamand and he elegantly sang his sonnet for strings and harpsichord accompaniment. Baritone Nikolay Borchev sang winningly as his more urbane rival Olivier who nevertheless struggled to keeps his feelings for the Countess in check. The character of the down-to-earth Count does not seem a very rewarding one, though baritone Christoph Pohl’s performance had dramatic credibility and was vocally assured. Mezzo-soprano Christa Mayer brought Clarion to life as an older actress with her claws in a wealthy man. The Italian singers were entreatingly enacted but not quite as well sung with Beomjin Kim sounding slightly tight despite impressive top notes and soprano Tuuli Takala not creating any particular impression. Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke gets even less from Strauss and his Monsieur Taupe was clearly a descendent of Mime. Kudos to the eight male servants who in their brief intervention are like a Greek chorus – and not just members of the Dresden State Opera one – and make their own comments on opera, ‘Soon everyone will be an actor’.

Not all of Richard Strauss’s operas were premiered in Dresden; though nine out of the total of fifteen he completed were although not Capriccio, yet the Saxon capital remains arguably the spiritual home for the composer’s farewell to opera and his nostalgia for a vanished world. There was no one better to guide the Staatskapelle Dresden through this premiere earlier this month of Herzog’s new production than Christian Thielemann who is now on a long goodbye to the Semperoper since it was recently announced he is not having his contract renewed as its chief conductor. From the virtuosically played prelude – that sextet for solo strings – when we were shown a relaxed Thielemann’s encouraging hand gestures, it is clear that we are in for a special evening as he led his musicians seamlessly through Capriccio’s chamber-like intimacy, then its more discursive moments, as well as musical diversions – such as the autumnal ‘moonlight interlude’ – by maintaining a fleet-footed conversational pace before soaring to the heights of the score’s lyrical splendour. Thielemann remains preeminent – probably unsurpassed – in the repertoire of the German Romantic composers of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Jim Pritchard

For more about Dresden State Opera click here.