![]()

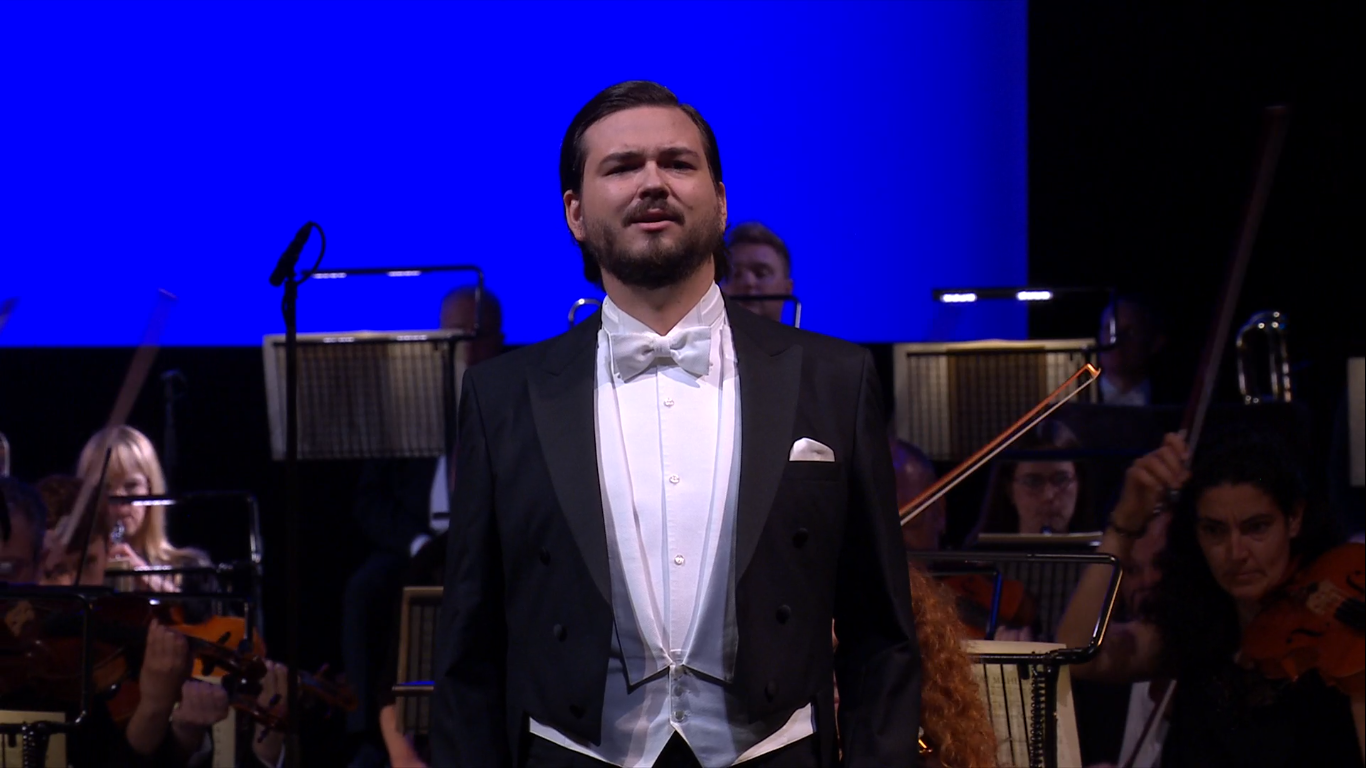

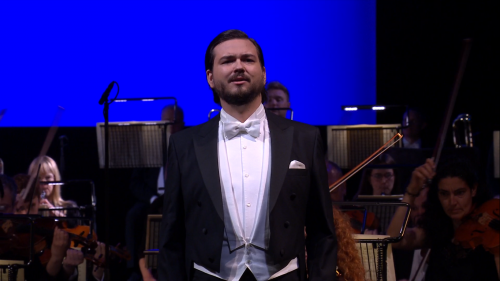

United Kingdom Dvořák and Mahler, London Philharmonic Orchestra’s Out of Chaos: Johannes Kammler (baritone), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Robin Ticciati (conductor). Filmed 2.7.2021 in the Glyndebourne Opera House (by Maestro Broadcasting and directed by Dominic Best) and available on Marquee TV from 16.7.2021. (JPr)

United Kingdom Dvořák and Mahler, London Philharmonic Orchestra’s Out of Chaos: Johannes Kammler (baritone), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Robin Ticciati (conductor). Filmed 2.7.2021 in the Glyndebourne Opera House (by Maestro Broadcasting and directed by Dominic Best) and available on Marquee TV from 16.7.2021. (JPr)

Mahler – Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen

Dvořák – Symphony No.8 in G major, Op.88

I have striven down the years – particularly when I was more involved in the world of Mahler and his music than I am now – to encourage audiences to consider the composer’s music as fundamentally ‘operatic’. And so, the often ‘precious’ interpretations of his Lieder are at odds with this because it is perceived to be the ‘Art’ of a singer to internalise them and rein in their emotions. It was so wonderful to see and hear the young German baritone Johannes Kammler – a name totally new to me – brings out the meaning of texts of Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen through his expressive face and voice and consequently this was a rather unique – and totally engrossing – account of these over-familiar songs about the misery of lost love.

Conductor Robin Ticciati gave a very interesting introduction to what we would be hearing saying: ‘It’s fascinating that Mahler started with these songs about travel, and a wayfarer so early in his compositional life. He was somehow fascinated by the Wunderhorn text and this idea of love and loss […] In the first [of four] songs you have the protagonist talking about marriage, and the lady he’s yearning for, and at the same time, the loss of that lady. The second song talks about the morning song of birds, of dew on the flowers, and yet he can no longer be with his love. The third song talks about the wind, the storms, the knife, the blade, the sharpness of loss, and yet at the end there’s hope. The fourth song has at its heart the funeral march of the First Symphony and the song ebbs out into the distance, into the hinterland, into the idea of journeying, the idea of lost, finding yourself.’

Kammler was born in Augsburg and received his first musical training from the Augsburger Domsingknabe, later studying singing in Freiburg im Breisgau, Toronto and at London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama where he did his postgraduate studies. ‘Wenn mein Schatz Hochzeit macht’ was yearning but there was a delightful contrast to the birdsong of the second verse before a suitably sorrowful penultimate line ‘Denk’ ich an mein Leid!’. ‘Ging heut’ Morgen über’s Feld’ began cheerfully enough as the wayfarer communicates Siegfried-like with a finch and Kammler brought radiance – thanks to a refined head voice – to thoughts of sunshine before the song’s more introspective ending. ‘Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer’ was sung with ferocity and an almost psychopathic fervour, yet it was rather unearthly at times as if the boy is (re)living his dream. Kammler gave it a sad, reflective ending full of resignation and regret against the tension in the orchestra. ‘Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz’ finds the wayfarer bidding a heartfelt farewell to the world and the wonderful range of the baritone’s voice was never better revealed than in its last lines and the descent from ‘alles’ to ‘Traum’ (‘alles, Lieb und Leid, und Welt und Traum!’). Kammler was quite brilliant and though Mahler utilises a fairly large orchestra I luxuriated in the spaciousness of Ticciati’s accompaniment of these rather lightly scored songs.

Dvořák was in his late-40s when he conducted the premiere of his Eighth Symphony in 1890: he had a considerable number of well-received compositions to his name already, though some of the ones we remember the Czech composer most by were still to come. The Eighth is a contrast of G major and its minor with the key fluctuating throughout, and I have read how it is characteristic of Czech music that joy and sadness are almost inseparable bedfellows. There was much light and shade – though not much darkness – in Ticciati’s eloquently phrased and paced account of this Dvořák symphony,

The Allegro con brio had a refined opening of striking vitality and it was notable for Katie Bedford’s flute which added the colouring of birdsong to this work here and elsewhere. (The music build and builds and isn’t there just a hint of Wagner’s ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ to it?) The London Philharmonic Orchestra played impassionedly and Ticciati effectively led them through all the changes of tempi and dynamics Dvořák demands. The Adagio began serenely (and I found myself thinking what I heard was a suggestion of a gypsy melody) before it became episodically march-like and then more triumphant and concluded like the summation of something and not just a second movement. The third movement (Allegretto grazioso — Molto vivace) has some of the most accessible music of the symphony with its skittish Mendelssohnian quality (its waltz-like nature saw Ticciati dancing on his podium). The final movement began with a fanfare of trumpets that the brass section repeated during a series of themes and variations as the music ramped up then became eerily quiet before Ticciati steered them onwards and upwards towards the musical summit of the final coda – and mixing metaphors – just like a train driver racing towards the light at the end of a dark tunnel. While I am loath to single out any of the totally accomplished LPO musicians: apart from Bedford there were several other virtuosic solo woodwind contributions, including Benjamin Mellefont’s clarinet, Jonathan Davies’s bassoon and Alice Munday’s oboe.

It was a very exhilarating conclusion to a concert that was almost perfect in miniature (barely 55 minutes); though why did we not get the entire programme, does Glyndebourne doubt its online audience’s concentration span? (For information only, those in the opera house also heard Jean-Féry Rebel’s Les Élémens and Ondřej Adámek’s Sinuous Voices.)

Jim Pritchard