Canada Various: Timothy Ridout (viola), Jonathan Ware (piano). Vancouver Playhouse, Vancouver, 5.11.2023. (GN)

Canada Various: Timothy Ridout (viola), Jonathan Ware (piano). Vancouver Playhouse, Vancouver, 5.11.2023. (GN)

Clara Schumann – Three Romances for Viola and Piano, Op.22

Mendelssohn – Viola Sonata in C minor, MWV Q14

Brahms – Viola Sonata in F minor, Op.120 No.1

Franck – Violin Sonata in A major (arr. viola)

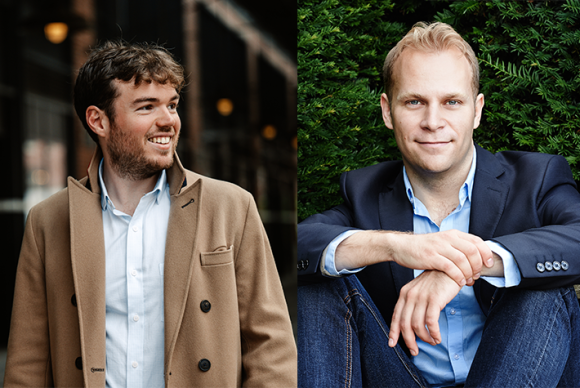

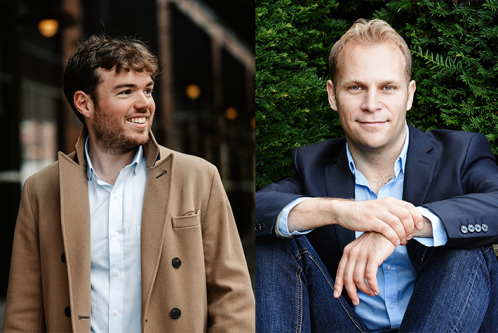

Just a week after a visit from young British superstar cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason, another young British rising star arrived: violist Timothy Ridout. Now 28, Ridout won the Cecil Aronowitz and Lionel Tertis Viola Competitions in 2014 and 2016 respectively, and has moved from strength to strength, culminating in a 2023 Gramophone Award for his recording of the Tertis arrangement of the Elgar Cello Concerto. Here the violist was joined by the attentive Jonathan Ware to play an enticing mix of nineteenth-century compositions and arrangements for viola and piano that few would have heard in live performance.

On this showing, one could only admire the strength and virtuosity of Ridout’s playing – which is disarming – and his complete tonal command over all ranges of the instrument. The performances of the Mendelssohn and Clara Schumann works were a great success, but the young duo’s strongly dramatic approach to arrangements of the better-known Brahms Clarinet Sonata, Op.120 No.1 and the Franck Violin Sonata were short on lyrical feeling and continuity.

Clara Schumann wrote her Three Romances for Violin and Piano in 1853 and dedicated them to violinist Joseph Joachim. In the version performed here, the piano part remains identical and the viola part is transposed. The duo combined for beautifully poised and lyrically telling readings, finding exceptional detail and balance throughout the three miniatures. The sensitivity of the expression was apparent from the opening bars of the first piece, and this was probably the richest show of feeling from Ridout. The viola arrangement really suits the sentiment.

The performance of the long-forgotten Mendelssohn Viola Sonata – written when he was 14 and only published in 1966 – was as almost as fine. Here it was the performers’ immense care on detail and structure that was notable. While the composition has its beauties, some of the gestures are clearly on the rhetorical side, so the 25-minute duration could easily outstay its welcome. Nonetheless, I found the venture redeeming. The piano part fit Ware’s fleet-fingered style perfectly, and the last movement, a set of variations, showcased both Ridout’s delicacy and refinement in softer passages and the sheer power of his attack in the headlong ending.

The more familiar works were the viola arrangement of the Brahms Clarinet Sonata Op.120 No.1, which was originally sanctioned, but not preferred, by the composer; and that of the Franck Violin Sonata, which was never sanctioned (unlike the cello version) but has had a following in France since the 1920s. Here the piano part and the middle-register scoring is largely left intact. The Brahms is one of the true staples of the viola repertoire. Ridout and Ware were not as successful in these works: the performance had considerable virtuosity and thrust, but otherwise remained lyrically unsettled and colder in temperament. I did find the viola version of the Franck successful in concept, potentially adding a burnished warmth to the original.

The Brahms was given a rather super-charged reading. There is no doubt that the work has turbulence in its opening movement (marked Allegro appassionata), even if that is hardly its defining characteristic, or late Brahms in general. Still, I have never heard the opening of the work as volcanic as here. Both Ridout and Ware seemed to be on the lookout for drama, and waves of strongly projected tempestuousness featured throughout the movement. What was largely missing was the wistful and yearning lyrical thread that has made the work so endearing in readings from William Primrose to Lawrence Power. In fact, dramatic forays were almost fully dichotomized from the softer, ruminative interludes, rendering the latter static, and not allowing the gradual building and release which is so characteristic of the composer. One problem was that the pianist did not paragraph the softer passages very well, failing to find the sort of characterization that would have prompted more expansive, poetic expression from the viola. Ware seemed to settle for prettiness in these contexts and propulsion everywhere else.

There can be few more lovely movements than the following Andante un poco adagio, and it was given some beautifully refined textures from Ridout. This was the most successful part of the performance, though I could not help feeling that there was a bit too much discipline in the violist’s playing, which made the experience slightly detached. There was not the suspended ‘speaking’ quality that one can sometimes hear. It is the fluidity and ease of the Allegretto grazioso and the wit, play and sheer joy of the finale which are enough to make one love this sonata. But that was not the feeling I got here: there were few smiles, and both movements turned out rather laboured, dissected by excessive point making.

The Franck had many of the same characteristics. The opening Allegretto was cleanly etched in Ridout’s treatment, but it was too cautious. It did not find the vulnerability in the expression, or the hints of passion just under the surface (compare Tabea Zimmermann). The propulsive Allegro is one of the favorite parts of this work, and here the articulation and scale in the earlier parts of the movement were perfect. Towards the end, however, fireworks began: a massive accelerando moving to an all-out climax, almost cinematic in its reach. The beginning of the Recitativo-Fantasia maintained a dirge-like emotionalism.

After the austerity of the opening, where did all this emotion come from, opening up a saga of sorts? The answer is that is that this is easy emotion to inflate, while the opening movement is more difficult and subtle. But Franck would not have wanted these sections glamourized. One always looks to the finale as a redeeming flow of spring water after the turbulence, but the artists once again seemed to seek dramatic strength rather than lyrical expansion, and it did not have the magical flow that we are used to. It did build to a rousing finish.

It is always fascinating to watch young artists build their interpretations. Much of the concert was a delight, but Ridout and Ware simply tried too hard to impress with virtuosity and thrust in the ‘bigger’ Brahms and Franck, not leaving much of a human face and resisting the calls of truly intimate expression. But that is exactly what it means to be a young performer! I think they should try these works a few more times so their interpretations settle. As for Timothy Ridout, in particular, his precision, agility and tonal strength are remarkable, but I still sometimes feel that he could use a longer and more free lyrical line than he chooses. Above all, we must be grateful for the uniqueness of this viola programme: it is doubtful that we will hear anything like it again.

The encore was an adaptation of the organ piece Le Soir by Louis Vierne, played by Ridout with a wonderfully restrained beauty. Now this was the spring water we were looking for.

Geoffrey Newman