United Kingdom R. Schumann, Nicodé, Schubert, Beethoven: Simon Callaghan (piano), Martin Roscoe (piano), Lot Music 2024 at Fair Oak Farm, Mayfield, East Sussex, 16 & 20.7.2024. (RB)

United Kingdom R. Schumann, Nicodé, Schubert, Beethoven: Simon Callaghan (piano), Martin Roscoe (piano), Lot Music 2024 at Fair Oak Farm, Mayfield, East Sussex, 16 & 20.7.2024. (RB)

I attended the Lot Music Course at Fair Oak Farm in East Sussex in July. This idyllic setting provided a perfect backdrop for a feast of music making from the participants and two outstanding recitals from the tutors, Simon Callaghan and Martin Roscoe.

16.7.2024 – Simon Callaghan Recital

R. Schumann – Arabeske, Op.18; Carnaval, Op.9

Jean Louis Nicodé – Phantasiestücke, Op.6 (Nos. 1 and 4)

Simon Callaghan’s recital focused on Robert Schumann while introducing us to the music of Jean Louis Nicodé. The latter was a Prussian composer who wrote in the latter part of the nineteenth Century and early part of the twentieth century. He was heavily influenced by Schumann but without having the earlier composer’s distinctive voice and imagination.

Callaghan’s performance of Schumann’s Arabeske was stylish and expressive. The rippling opening section moved along briskly with Schumann’s poetic sensibility coming to the fore. Eusebius gave way to Florestan in the following two sections, and I liked the sense of edginess and disquiet which Callaghan brought to the music. The piece ended on a note of rapt dreaminess.

Schumann’s Carnaval is one of the best known and most performed of his early piano works. It depicts masked revellers at Carnival, a festival before Lent. Schumann gives musical expression to the different sides of his personality, to his friends and colleagues including Clara, Chopin and Paganini, and to the characters from the commedia dell’arte.

Once again Callaghan did an excellent job capturing the manic sides of Schumann’s personality. The opening chords were arresting and authoritative, commanding attention from the audience. The subsequent vivo section was highly virtuosic while giving vent to Schumann’s volatile manic-depressive side. The characters from the commedia dell’arte emerged from the score as colourful, coquettish and capricious. The portraits of Chopin, Chiarina and Estrella were delightfully drawn while Paganini was a virtuoso tour de force. Callaghan observed the Prestissimo marking in ‘Papillons’ and in so doing displayed breathtaking finger-work while ‘Reconnaissance’ had rhythmic bounce and energy. Callaghan seemed willing to take risks in this performance and this had the effect of energising and revitalising this great staple of the repertoire.

I enjoyed listening to the two pieces by Nicodé: the first was highly agitated and the second more lyrical with elfin Mendelssohnian textures. The music is clearly indebted to Schumann and deserves to be performed more widely.

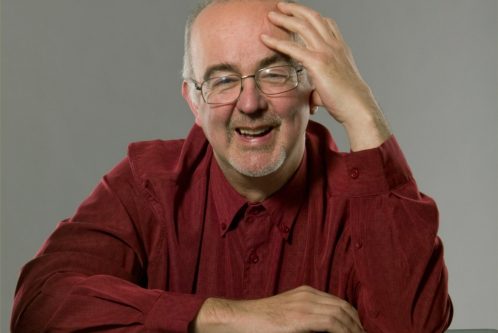

20.7.2024 – Martin Roscoe Recital

Schubert – 4 Impromptus D899

Beethoven – Sonata in C minor, Op.111

Martin Roscoe opened his recital with the first of Schubert’s two sets of Impromptus. These pieces were written in 1827 towards the end of the composer’s short life. Only the first two pieces in the set were published during Schubert’s lifetime.

I was struck by the muscularity of the playing, the big dynamic contrasts and Roscoe’s extraordinary ability to make the piano sing. The C minor Impromptu opened in dramatic fashion with unison octaves. The contrast with the ensuing hushed unaccompanied melody was startling. Roscoe allowed the piece to blossom out organically as the melody was transformed from a march like funereal theme into one of those moments or rare lyrical enchantment in Schubert. The triplets which opened the Second Impromptu in E-flat cascaded down the piano in a carefree way. The modulation to E-flat minor was startling and I was particularly struck by the extraordinary change in colour. Roscoe’s performance of the coda to the piece was incendiary and made me think about the radical nature of this music. Roscoe transformed the G-flat Impromptu into a luminous song without words. One could not help but be swept up in Schubert’s gorgeous melodies. The arpeggios which open the final Impromptu in A-flat were beautifully shaped. As the melody emerged the music became more playful and infused with Viennese charm. Once again Roscoe emphasised the big dynamic contrasts in this piece. The middle section was highly agitated and turbulent, and one could hear the composer’s howls of anguish.

Beethoven’s final Piano Sonata in C minor is one of the most radical works in the repertoire. It was written in 1822 and it is unique in the way it seems to fuse music and philosophy. Beethoven used the key of C minor for some of his most turbulent pieces and the first movement of the sonata opens in this key. This gives way to the hymn-like Arietta of the second movement where the music becomes more ethereal.

Roscoe played the opening of the sonata, with its memorable diminished seventh intervals, with considerable dramatic force and impact. He made no attempt to disguise Beethoven’s discords, reminding us of how modern this work is. He brought out the sense of struggle and conflict in the contrapuntal episodes while the elements of harmonic surprise and dark whirling menace of the textures were conveyed brilliantly. The seraphic second movement opened in a calm meditative fashion. Roscoe paid close attention to tempo relationships throughout this movement. The pulse remained steady throughout and the composer’s subdivision of note values was allowed to take effect naturally and organically. The famous ‘boogie-woogie’ variation was a little slower than some other interpreters, but it was much better integrated into the musical narrative. In the final variation, the musical became increasingly ethereal as Roscoe seemed to commune with the divine.

Overall, these were both first-rate recitals which succeeded in illuminating great staples of the repertoire in new and original ways.

Robert Beattie

Thank you Robert. A lovely review and reminder of two most wonderful recitals.