Hungary VI. MiraTone Festival and Academy, Budapest, 26.8 – 1.9.2024: (AK)

Hungary VI. MiraTone Festival and Academy, Budapest, 26.8 – 1.9.2024: (AK)

The annual MiraTone Festival and Academy project is the brainchild of founder director Miranda Liu. The 28-year-old California born American-Chinese violinist was a student at the Salzburg Mozarteum 2007–13, then from 2013 at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music, Budapest, where she graduated in 2018. In the meantime, at the age of 20, in 2016 Liu was appointed as concert master of András Keller’s Concerto Budapest, a post which she still retains. At the same time, in 2019, Liu set up her annual MiraTone project which grows from strength to strength. And she is also a busy solo and chamber music violinist, speaking several languages from which I can vouch for her perfect command of Hungarian.

This year’s MiraTone festival, the sixth since its foundation, was packed with concerts as well as masterclasses. During the seven days of the festival, twenty established performers delivered ten solo and chamber music concerts, while MiraTone Young Artists presented eight further concerts. Mind-blowing riches with mind-blowing variety.

I opted to attend three afternoon concerts of slightly shorter than evening-concert lengths, two focusing on twentieth and twenty-first century music, one on transcriptions.

30.8.2024 – Piano recital by László Borbély

Borbély presented a very interesting progamme of Bartók and Ligeti pieces, twelve from each of the composers in alternating order. Bartók was represented by pieces from his Mikrokosmos (Nos. 126, 143, 140, 109, 107, 135, 146, 113, 101, 97, 129, and 147), while in between those pieces we heard eight from Ligeti’s cycle of Eighteen Etudes (Nos. 15, 4, 2, 7, 1, 12, 5 and 6) as well as four from his Musica ricercata (Nos. 5, 8, 9, 11).

Borbély’s programming of Bartók-Ligeti-Bartók-Ligeti-etc. was a brilliant idea; it could have clearly shown us Bartók’s influence on Ligeti and Ligeti’s great respect for Bartók. However, in practice, only those who were familiar with all or at least some of the pieces could have grasped this concept, assuming that this was the actual concept.

We were informed that the programme would be presented in six blocks of four pieces without any interval but, in the event, Borbély grouped sometimes three, sometimes five pieces. Furthermore, he often played attacca, while other times he held poses between pieces. I am familiar with some of the Mikrokosmos pieces, which helped me to navigate, but couple of times I was unsure whether I was listening to Bartók or Ligeti.

It is hard to be sure what Borbély’s aim might have been. Was he playing to a general audience, to Bartók/Ligeti experts or just for himself? His preparation was clearly painstaking to the extent of his masterly, almost artistic display of all music on the piano music stand. Carefully pasted on large blocks of hard boards, all music was displayed from the beginning, vacating the piano stand block by block. Apart from couple of occasions, Borbély eliminated the need for page-turning. His playing was fully committed – more passionate on the percussive than on the lyrical side – and faultlessly virtuoso.

The audience was fully attentive and fully appreciative, but I am not sure if they were experts in Bartók-Ligeti piano music or were blissfully lost (as I was at times). I also note with interest that Borbély played the whole programme from music. Nothing wrong with it but, in my experience, it is unusual for an artist of Borbély’s calibre and standing.

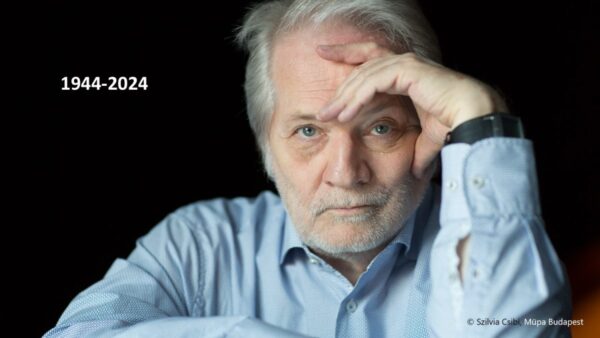

31.8.2024 – Memorial Concert for Peter Eötvös

To pay respect to the late famed composer/conductor Peter Eötvös – whose death in March 2024 left a devastating void in the musical world – this concert included three works by Eötvös, four world premiere compositions in memoriam Peter Eötvös as well as Lutoslawski’s string quartet.

Commissioned by Patricia Kopatchinskaja in 2015, Eötvös’s ‘A Call’ for solo violin is the composer’s response to a quote from James Joyce, Ulysses, Episode 11, Sirens. Miranda Liu presented the piece with full command of the technical challenges such as tricky harmonics, double stops, playing under the violin’s bridge and left-hand pizzicato accompaniment to a cantilena melody.

Eötvös’s ‘Shadows for Orchestra’ (1996) includes a substantial cadenza for the solo flute, which here received loving care from Noémi Győri: her last note created a particularly moving moment.

Eötvös’s ‘Derwischtanz’ for solo clarinet or three clarinets (1993) is fascinating in concept and here received a equally fascinating performance by Csaba Pálfi. Throughout the performance he kept slowly turning round in full circle, thus alternating his exquisite tone colours for the audience. Pálfi knows this piece intimately, he played it from memory.

Whether by accident or design, all four world premiere compositions in memoriam Peter Eötvös included the flute, played in all pieces by Noémi Győri. Her commitment to newly commissioned works is tireless and commendably productive. In three of the four world premiere pieces Győri was partnered by clarinettist Pálfi; one of the compositions included a cello (played by Bartosz Koziak) with the flute and clarinet.

All four world premiere compositions can be deemed as noble salutes to Eötvös. Péter Tornyai’s ‘Une seule melodie lontaine’ gives a lot of rhythmic freedom to the solo flute. The last note particularly caught my attention: it starts on a relatively low register note and slides upwards with a diminuendo. In his ‘In Memoriam E.P.’ for flute and clarinet, Gergely Vajda presents a masterly dialogue between the two instruments, exploring the full registers of both, while providing exciting moments for the listeners. Bálint Horváth also composed for flute and clarinet (‘From Heat, From Light’) with well-planned structure for the two-instrument dialogue while Csanád Kedves added a cello part in his ‘Geseent Solitude’, presenting interesting soundscapes as well as lovely cantilena clarinet notes often accompanied by the cello.

Owing to clash of dates I was unable to stay for the performance of the Lutoslawski string quartet. However, the Eötvös pieces and the new pieces composed in his memory provided a deeply moving occasion.

1.9.2024 – Piano recital by Ilya Kondratiev

The theme here was piano transcriptions and Russian pianist Kondratiev, for ten years residing in London, gave convincing musical arguments for the genre. He presented Bach’s transcription of a Marcello oboe concerto, Liszt’s of two Haydn orchestral pieces, Harold Bauer’s of César Franck’s Prelude, fuge and variations for organ and Busoni’s Bach’s Chaconne arrangement.

Kondratiev’s approach to all of the pieces was passionate commitment. With the exception of the Busoni arrangement, he played his programme – including his encore that is the Liszt-Schubert Gretchen am Spinnrade – from memory. Kondratiev is a virtuoso pianist and put his technique to good use in his demanding programme.

I was surprised to see the piano lid fully open in the opening Bach transcription, especially as the concert venue in the FUGA building is small (about half of the Wigmore Hall size). To my preconceived expectation, Kondratiev’s full on sound volume was too loud for Bach but the second movement was beautifully sung. The very fast speed of the third movement would have frightened any oboist (as well as the original composer Marcello) but herein lies the compromise or recreation of transcriptions.

According to the printed programme, the second item was Liszt’s transcription of Sarabande and Chaconne from Haydn’s opera Almira. If it was Haydn, it would have been from his opera Armida, otherwise it would have been from Handel’s Almira. With the Liszt score on hand, one could check the relevant sections in both operas, but I will leave this task for another time.

I am not quite sure why Harold Bauer transcribed César Franck from organ to piano – other than giving pianists the chance to play this work – but Kondratiev’s committed presentation was fully convincing of the transfer.

Busoni’s transcription of Bach’s Chaconne for solo violin is a beast, definitely not for a faint-hearted pianist. Kondratiev went for it with full force yet producing crystal clear voice leading in spite of the tsunami of notes. In addition, as he played (only) this piece from music, Kondratiev negotiated all digital page turns with his left foot. With much pedalling also necessary, praise is due for Kondratiev’s left foot technique as well as for his whole recital.

Agnes Kory