United Kingdom Pärt, Tan Dun, Lutoslawski: Colin Currie (water percussion), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Hannu Lintu (conductor). Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, 29.3.2025. (CK)

United Kingdom Pärt, Tan Dun, Lutoslawski: Colin Currie (water percussion), London Philharmonic Orchestra / Hannu Lintu (conductor). Queen Elizabeth Hall, London, 29.3.2025. (CK)

Pärt – Symphony No.1 (Polyphonic)

Tan Dun – Water Concerto

Lutoslawski – Symphony No.3

With Finnish conductor Eva Ollikainen indisposed, it was fortunate that her compatriot Hannu Lintu (admired here by John Rhodes for his Saariaho and Nielsen with the London Symphony Orchestra only three days earlier) was on hand to take on this challenging London Philharmonic Orchestra programme, and to take it on unchanged. It also proved a good move to perform the concert in the Queen Elizabeth Hall rather than the Royal Festival Hall – smaller and more intimate than its imposing neighbour and better suited to the piece which most people in the audience had come to hear and see. The lights were low; each player’s music stand was illuminated.

Tan Dun’s music can be both hypnotic and exciting: I remember the impact of his breakthrough score for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, a selection from which was played by China’s Shenzhen Orchestra on their UK tour last year. His Water Concerto is dedicated to Toru Takemitsu, and it was Takemitsu who the music brought to mind – both for the importance of visual theatre (remember those enormous coloured ribbons in From me flows what you call Time?) and for the stretches of musical uneventfulness (it might have seemed a long 27 minutes to some of the orchestral players). Most of us in the audience were gripped less by the music than by curiosity about what Colin Currie and his two assistants were going to do next.

That is not a fair distinction, since the piece is not about music, but about sounds and how we listen to them. And what sounds! The piece began with Currie at the back of the hall, the other two players on the stage at extreme left and right, playing waterphones – instruments that hold water, with metal prongs that are bowed and amplified with magical effect. We could have been on Prospero’s island, enchanted by Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight, and hurt not. Each of the players had a large glass bowl (Currie had two), in which various objects were dipped (including hands, producing an amplified splashing). The surface of the water became the skin of a drum as Currie attacked it with an upended glass in each hand; the sound of small gongs bent out of true as they were immersed; a long glass tube, tapped on its rim, produced different notes according to its depth in the water. And so on.

The orchestra? The strings slid around, coiling and uncoiling like a sleepy snake. Brass players tapped their instruments or blew through their mouthpieces. A cello had a schmoozy solo. A clarinettist played a noisy kazoo. As a change, Currie made air noises with swishing chopsticks or went off to play a marimba in front of the heavy brass. The soloists’ rhythmic patterns were sometimes more interesting than the sounds themselves: widely separated on stage, their unanimity in synchronising complex rhythms was perhaps the most impressive aspect of the performance.

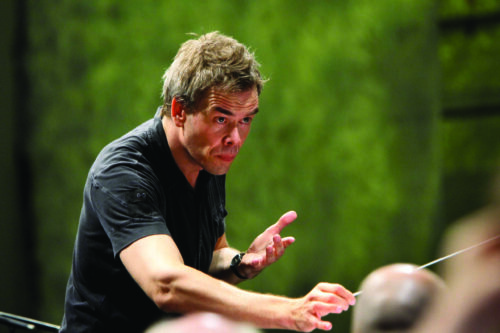

Celestial doodling, I jotted as the piece began: but then I started to really listen. It is quite an experience, and no praise can be too high for Currie and his two unnamed colleagues. It was embedded between two symphonies from the second half of the twentieth century, Estonian and Polish, both written under conditions of Soviet oppression, both conducted by Lintu with flair and authority. He is a very tall man, a commanding figure; and with his left hand signalling to the players high over his head – as it frequently was – he is taller still.

Arvo Pärt wrote his First Symphony before he was thirty, inspired by musical processes and influenced by the Second Viennese School. It is a twelve-tone work, not too frightening, but possibly disturbing for those who love the Pärt of Spiegel im Spiegel. The first movement, Canons, sported some attractively angular lyricism and some fine writing for the pair of horns; in the second, Prelude and Fugue, the horns again caught my ear, as did a jolly section featuring syncopated pizzicatos from the strings and chirruping woodwind, and a more sinister episode of dark sounds from clarinet and bassoon over cellos and double basses grubbing away at a complicated rhythm.

The final work was an unquestioned masterpiece. Lutoslawski had to find his own way into writing a symphony. With his Third he found a form that worked for him – two movements, played without a break: the first preparatory, laying out his materials, the second a fully developed musical argument. Unlike Shostakovich, Lutoslawski’s composing was sealed off from the public events of his time: yet it is hard not to hear the terse, hammering four-note motif with which it begins and ends as an iron fist, a modernised, even mechanised version of the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth.

The opening movement – flying rags and shreds of themes – has a preparatory, at times tentative quality. Pizzicato double basses signal the beginning of the second movement: a stumbling march spreads through the strings. There is beauty and barbed wire: the more the pain and tension seem to grow, the greater the beauty. And when the four-note figure crashes in for the last time, it seemed – at least, in this fine and exponentially intense performance – more like an achievement, an arrival than a door slammed in the symphony’s face. Lintu and the LPO were magnificent.

Chris Kettle