United Kingdom Ravel: Circa (Yaron Lifschitz [artistic director, stage and lighting designer], Libby McDonnell [costume designer]), BBC Singers, London Philharmonic Orchestra / Edward Gardner (conductor). Royal Festival Hall, London. 23.4.2025. (CSa)

United Kingdom Ravel: Circa (Yaron Lifschitz [artistic director, stage and lighting designer], Libby McDonnell [costume designer]), BBC Singers, London Philharmonic Orchestra / Edward Gardner (conductor). Royal Festival Hall, London. 23.4.2025. (CSa)

Ravel – Daphnis and Chloé; La Valse

New ways of performing classical music have long sparked heated debate. Are traditional classical settings too archaic and intimidating for today’s audiences? Can attempts to modernise the concert experience enhance the performance or undermine it? How can concert promoters and musicians democratise what some claim to be an elitist and outmoded model without distracting from or dumbing down the ultimate end-product, namely the music itself? These questions are pertinent when considering the aims and ambitions of Southbank’s Multitudes, a series of concerts billed as ‘an electrifying new arts festival powered by orchestral music’. Funded by Arts Council England, the Festival’s organisers seek to open the doors of classical music to a wider, younger and more diverse audience by combining orchestral works with dance, film, poetry, visual art and other musical genres in a way that is challenging and arguably, more engaging.

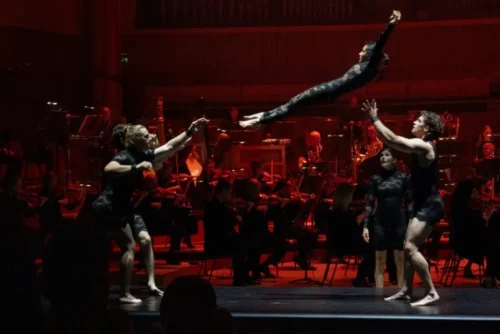

In the first concert of the series, the London Philharmonic Orchestra under its Principal conductor Edward Gardner joined forces with Circa, the Brisbane based contemporary circus group in a daringly gymnastic, cross-pollinated realisation of two starkly contrasting works by Maurice Ravel: Daphnis and Chloé and La Valse.

Daphnis and Chloé, described by Ravel as a ‘symphonie chorégraphique’ was commissioned in 1912 by Serge Diaghilev for the Ballets Russes and Choreographed by Michel Fokine and designed by Léon Bakst, the ballet premiered in Paris in the same year to mixed reviews. The performers declared the work’s gorgeous harmonies, impressionistic textures and complex orchestration too demanding, while the audience found the ancient and labyrinthine Greek love story between the goatherd Daphnis and the shepherdess Chloé too difficult to follow. There are many challenges in depicting the tale of star-crossed young lovers who survive a kidnapping by pirates and an earthquake, a sensual reawakening and a Bacchanalian wedding. Consequently, the ballet is usually performed in concert and rarely staged.

La Valse, a dark and ironic tribute to Johann Strauss II was also originally conceived for ballet, but one rejected by Diaghilev, and since then almost invariably performed as a concert piece. Widely viewed as a metaphor for the disintegration of European civilization after the horrors of the First World War, Ravel described his work as ‘a sort of apotheosis of the Viennese waltz, mingled in my mind with the impression of a fantastic, fatal whirling’.

The decision by the production team to mount Daphnis and La Valse as abstract, semi-danced and essentially acrobatic spectacles was a bold step and required a leap of the imagination, but one that came with advantages and disadvantages. The troupe, under the skilful direction of Yaron Lifschitz, gave a towering performance, in every sense of the word. Its members, clad in black lace Victoria’s Secret (or perhaps not-so-secret) style tunics for Daphnis, and loose-fitting track suits in La Valse, were sturdier, stronger and more full-bodied than conventional ballet dancers. When standing still on a narrow, raised platform immediately in front of the stage, they appeared solid, sculptural, and timelessly beautiful, reminiscent of the figures in Picasso’s neoclassical paintings. In action, they were less delicate and emotionally attuned as ballet dancers, sometimes gesturing clumsily or landing heavily with a noisy thud. Yet they also pulled off incredible feats of circus-like daring, rotating, summersaulting, cartwheeling and body flipping with astonishing agility. Whether hanging perilously in the air or forming an eleven-strong human pyramid before tumbling vertically to earth, the audience frequently held its breath.

Meanwhile, the 100-strong LPO, seated on the platform behind the action, packed a mighty punch. Gardner coaxed a rich sonority from the strings, with floating glissandos from harps, and sensuous interjections from the woodwinds, while in Daphnis, the fine-voiced BBC Singers sighed and ah’d effectively.

An enjoyable and entertaining evening to be sure, but did the boisterous fun of the circus add to or detract from the orchestral glory of these scores? For one member of the audience at least, the big top acrobatics, spectacular though it was, became a distraction which encroached on the emotional power and sublime beauty of Ravel’s music. Yet tumultuous applause from a capacity crowd suggested that that this view was not shared by the majority.

Chris Sallon