Italy Rossini Opera Festival 2025 [1] – Rossini, Zelmira: Soloists, Coro del Teatro Ventidio basso (choir leader: Pasquale Veleno), Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna / Giacomo Sagripanti (conductor). Auditorium Scavolini, Pesaro, 10.8.2024. (AB)

Italy Rossini Opera Festival 2025 [1] – Rossini, Zelmira: Soloists, Coro del Teatro Ventidio basso (choir leader: Pasquale Veleno), Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna / Giacomo Sagripanti (conductor). Auditorium Scavolini, Pesaro, 10.8.2024. (AB)

When discussing Zelmira, Rossini’s last opera for Naples, Richard Osborne, in his still indispensable monography on the great composer, referred to nineteenth-century commentator Henry Chorley in lamenting that the work’s ‘“songs of parade and passion’ are not for every day, or every generation.”’ Chorley and Osborne would have had to look no further than this year’s opening premiere of the 46th Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro to see and hear that their pessimism certainly does not apply to 2025.

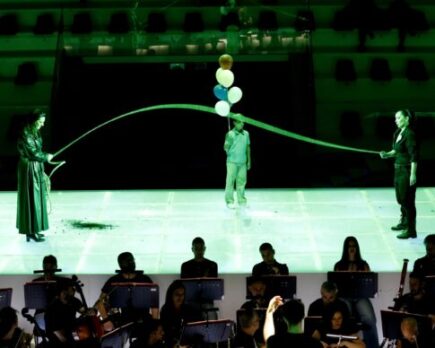

The performance took place in the Auditorium Scavolini — a multipurpose sports hall in Pesaro’s city centre. Here, right in the middle of the hall on a platform the size of a tennis court, constructed from internally lit square blocks and riddled with pits (one housing the orchestra, other ones containing water or earth), Calixto Bieito and his collaborator Barbara Horáková staged a bold yet curiously restrained reading of Rossini’s final Neapolitan opera. Given the complex story and the director’s reputation that could have easily dissolved into confusion and excess, the evening instead became a study in psychological compression and – above all – supreme and sublime music making.

Bieito, the enfant terrible of European opera direction, delivered a minimal, almost introverted staging in which blood, gore, and machine gun fire were mercifully absent. The production instead placed its focus on the internal struggles of the principal characters and used only a few symbolic visual cues and props to evoke the larger political drama: Helmets, placed on the stage by the chorus (costumed as soldiers), marked the ever-present threat of war on the island of Lesbos where the action takes place; a teddy bear served as a poignant stand-in for Ilo’s battlefield trauma; reels of film rummaged by Emma and Ilo served as metaphor for their desperate search for truth regarding the actions of Zelmira, falsely accused of regi- and patricide, as well as of trying to assassinate her husband.

A trio of silent figures — the young son of Zelmira and Ilo (noticeably ignored by both), a near-mythical old man visible only to the boy, a black-winged angel — hovered around the action like an allegorical frame: Fate, perhaps; or simply that layer of meaning which the libretto, for all its intrigue, leaves unsaid.

Dramaturgically, Bieito showed little interest in untangling the opera’s labyrinthine plot (there were surprisingly no surtitles). Instead, he concentrated on the relationships: Zelmira’s absolutely loyal love for her father, her hesitant intimacy with Emma (here rendered explicitly as romantic), and her emotional withdrawal from her husband and son. Antenore, her great opponent, too, was cast not as a mere villain but as a man crushed by self-doubt, drawn into manipulative co-dependence with the sinister Leucippo — also here his lover.

Whether all this clarified or obscured the work’s narrative arc is debatable. But the psychological coherence it provided to the key scenes allowed the cast to work with rare emotional specificity.

It is difficult to overstate how demanding this space was. With no acoustic shell, a vast open ceiling, and the audience placed around all four sides, singers had to move constantly — often singing while walking, turning, or even ascending the stairs that surrounded the central platform. Yet all members of the cast sang with such vocal perfection that it bordered on the miraculous.

In the title role, Anastasia Bartoli proved herself once more as a Rossinian soprano of the highest rank. Her voice, darkly coloured yet evenly produced across the registers, was never forced and always expressive. She sang with an unwavering sense of line and impressive emotional intelligence. In the aria ‘Perché mi guardi e piangi’, Bartoli floated phrases of exquisite restraint, matching the music’s plaintive chromaticism with clean, unexaggerated expression. Hers is not a decorative Zelmira, but one whose moral centre anchors the entire performance.

Equally memorable was Lawrence Brownlee as Zelmira’s husband Ilo, whose bel canto technique continues to set the standard internationally. Brownlee’s opening aria ‘Terra amica’ was not merely a vehicle for agility but a fully shaped meditation of longing. His voice, brighter than Bartoli’s but equally controlled, carried through the acoustic with astonishing clarity, and his dramatic response to Zelmira’s supposed betrayal was rendered with moving dignity.

Enea Scala sang Antenore with a combination of technical brilliance and psychological detail. His timbre, sharper-edged than Brownlee’s, provided needed contrast, and he made full use of Antenore’s oscillation between bravado and fear. That he managed to sing his Act I cabaletta hanging half-inverted from a suspended block without the slightest impact on pitch or phrasing speaks for itself.

Among the ‘secondary’ roles (there were really none here), Gianluca Margheri was a compelling Leucippo, his baritone full of menace and control. Marina Viotti sang Emma with burnished warmth and pliant tone, forming a beautifully shaded vocal blend with Bartoli. Marko Mimica, as Polidoro, lent authority and focus to a role that often disappears behind the plot mechanics.

The chorus, under the direction of Pasquale Veleno, navigated the difficult spatial demands with unflinching discipline and full-bodied tone. Their appearances — often from staircases and balconies between the audience — added to the immersive atmosphere without ever becoming disjointed.

Perhaps the most consequential presence of the evening was that of Giacomo Sagripanti at the helm of the Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna who made the impossible seem easy. In a space where coordination is difficult and subtlety easily lost, Sagripanti achieved a unity and musical finesse that can only be described as extraordinary. He guided the orchestra through the chromatic turns and surprising modulations of the music with a hand that was both confident and supremely responsive.

Under Sagripanti, Rossini’s score – using a lower timbre and more minor keys than most of his others – was never muddied or exaggerated: the textures remained transparent, the overall flow organic, and the tempi ideal. Most importantly, he followed the singers with the utmost sensibility — each rallentando, each phrase ending, was shaped in real time.

A few scattered boos for the production team at the end were perhaps inevitable — Bieito’s interventions rarely go unpunished by the conservative contingent. But they were drowned out by ovations for the cast, orchestra, and conductor.

Zelmira may not be for every day or every generation, but in 2025, in a sports hall in Pesaro, it found perfection. It will be difficult to hear this opera performed better — or more convincingly contextualised — anytime soon. This was Rossini at his most serious — and his most sublime.

Andreas Bücker

Featured Image: Zelmira at the Rossini Opera Festival 2025

Production:

Director – Calixto Bieito

Staging – Calixto Bieito and Barbora Horáková

Costumes – Ingo Krügler

Lighting – Michael Bauer

Cast:

Polidoro – Marko Mimica

Zelmira – Anastasia Bartoli

Ilo – Lawrence Brownlee

Antenore – Enea Scala

Emma – Marina Viotti

Leucippo – Gianluca Margheri

Eacide – Paolo Nevi

Gran Sacerdote – Shi Zong