France Verdi, Aida: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Opéra national de Paris / Michele Mariotti (conductor). Livestreamed (directed by Mathilde Jobbé-Duval) from Opéra Bastille, Paris, 10.10.2025. (JPr)

France Verdi, Aida: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Opéra national de Paris / Michele Mariotti (conductor). Livestreamed (directed by Mathilde Jobbé-Duval) from Opéra Bastille, Paris, 10.10.2025. (JPr)

The previous Paris Aida I reviewed (here) from Christof Hetzer began at the gala opening of a new ethnographical collection in a grand museum; and a recent Aida at New York’s Metropolitan Opera (here) was set against the backdrop of an archaeological dig and an Egyptian tomb being ransacked for its artefacts. There cannot in 2025 be a performance of Verdi’s Aida as the composer’s conceived it. Every news production needs to counteract the late Edward Said’s accusation of Aida’s ‘Orientalism’ and how the opera represents how Western Imperialism has led to cultural appropriation. This is taken to the extreme in Shirin Neshat’s Aida which has arrived, much revised, in Paris (in a co-production with the Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona) from outings in Salzburg in 2017 and 2022.

Neshat is an Iranian photographer and visual artist who now lives in New York. She was shown speaking during the interval of the livestream, and of course she mentioned Said while explaining how ‘women have been at the core of my inspiration, particularly Iranian women as people who have struggled a lot but have been very defined and constantly very rebellious.’ Despite these women being ‘submissive, oppressed and under great pressure’ they remain ‘very powerful, very vocal and not losers’. Sadly, this does not get to the stage and while Aida may be ‘rebellious’, even Amneris as the daughter of the King of Egypt is demeaned by the soldiers (who we also see on film abusing women prisoners physically and sexually). Considering Aida and Amneris, Neshat said how she ‘sympathises with both women in the way they are trapped in their own oppressive environments. They are not free; the only time we see people free is when they die.’ What Neshat’s staging actually focusses on is another point that she makes about how in many regimes throughout the world ‘It is very difficult to separate religion from the ruling party’ and it is often clerics who say ‘We must kill, we must kill.’

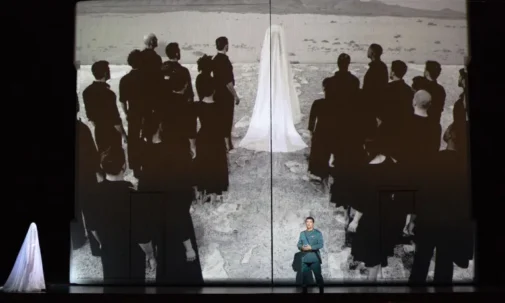

Neshat’s Aida is far removed from the traditional palaces and pyramids we associate with the opera from productions of yesteryear. Robert Carsen’s current Covent Garden Aida (review here) references warmongering countries such as America, Russia, China and North Korea. For Neshat the problem she wants to highlight is religious intolerance and absolute fanaticism of an anti-Western religious theocracy leading to the repression of dissent and the equality of women, particularly, as well as other minorities. However, she does this by turning the stage of the Opéra Bastille into an art installation which on many occasions – despite some haunting video imagery of today’s world – dwarfs the singers. (Apparently Riccardo Muti who conducted the 2017 Salzburg premiere refused to allow this to happen.) Neshat projects her films on Christian Schmidt’s huge, occasionally revolving, faux concrete, off-white cube against – or within – which the action (such as it is) takes place. One side has a couple of doors for entrances and exits, and the cube can split and arrange its two halves. There is colour from time to time, but the overall impression is of a monochrome world.

What we see begins and ends with a boat on the water – a too familiar sight for some countries – presumably taking those fleeing a repressive regime to, hopefully, a more welcoming country. During the first two acts our eyes are drawn more to the changing images – especially if watching on a screen – than to what is happening in front. Anyway, Neshat’s political treatise is clear enough (well, give or take), soon enough and there is diminishing returns as the opera proceeds. Soon we see a fortress in the distance and a naked woman who is veiled in white by men and women on a shoreline (happening whilst Radames sings ‘Celeste Aida’). It is later as Aida sings ‘O patria mia’ when we get the most colour on film as there is a funeral procession (for her father Amonasro?) through a desert as women scrabble in the dirt possibly digging a grave. The changes between acts features weather-beaten faces projected on the cube and overly tall, veiled figures in black silently cross the stage. These also appear at significant moments during the events of the opera and are aided by Felice Ross’s lighting casting forbidding shadows.

Viscerally effective moments included the sacrifice of a goat by Radames in the temple scene which see the Priestess singing onstage. Later the Act II ‘Triumphal March’ will be proceeded by a naked women decapitated (?) by Radames. The background film to this act’s ‘ballet’ shows men and women being physically and sexually assaulted by soldiers, whose brutality includes them threatening Amneris earlier and later seemingly gunning down those prisoners the opera tells us Radames has freed. The final two acts – within the context of all that had gone before – is played out more like a semi-staging, despite corpses being carried on for Act III and Aida and Radames sinking to the floor at the end as they are resigned to their fate, after singing their duet far apart inside the cube.

Elsewhere the stage pictures are dominated by the different faiths and denominations Neshat shows us, with amongst others the bearded men of the Greek Orthodox Church (with the High Priest one of them) and Sufis. Radames is in military uniform, Aida in simple black, Amneris in a variety of flowing gowns; canary yellow, red and finally, white, and Amonasro is in black waistcoat, shirt and trousers.

It was the singing from all concerned and the playing of the Paris Opera Orchestra under Michele Mariotti which redeemed Neshat’s Konzept. The singing of the chorus was outstanding, helped by being often left standing lined up within the acoustically supportive cube. What we heard from Mariotti and his excellent-sounding orchestra often indulged in the pomp and pageantry of Verdi’s music not otherwise replicated in Neshat’s direction.

One of the world’s greatest tenors, Piotr Beczała, was in wonderful voice again as Radames. He began with a resplendent ‘Celeste Aida’ though there was no pp morendo, just a solidly held B-flat. The rest of the opera revealed Beczała’s artistry at its best, although I wish his Radames had not been quite so indistinguishable from his recent performances as Don José and Manrico that I have seen.

His compatriot Ewa Płonka was replacing an indisposed Saioa Hernández as Aida, and her portrayal was straightforward – almost traditional I might add – seemingly due to a lack of direction from Neshat whose concerns might have been elsewhere, rather than with the opera’s leading characters. Płonka sang with dramatic intensity, a full voice and an impressive range of emotion in her two major arias.

Swiss mezzo-soprano Ève-Maud Hubeaux began a little insecurely, in my opinion, as Amneris but from then on her expressive voice went from strength-to-strength. Her dramatically effective Amneris was a force to be reckoned with – despite coming off second best in her confrontations with the soldiers – and someone clearly used to getting her own way, until she doesn’t.

Russian baritone Roman Burdenko was a physically intimidating Amonasro and sang with a suitably stentorian baritone. Basses Alexander Köpeczi and Krzysztof Bączyk sounded authoritative as Ramfis and the King, but their characters have never seemed blander or more insignificant. Finally, Margarita Polonskaya had a greater presence than usual as the Priestess and Manase Latu was a strongly sung Messenger.

Jim Pritchard

For more about Paris Opera Play click here.

Featured Image: [front] Piotr Beczała (Radames) and Alexander Köpeczi (Ramfis) © Bernd Uhlig/OnP

Creatives:

Director and Video – Shirin Neshat

Set design – Christian Schmidt

Costume design – Tatyana van Walsum

Lighting design – Felice Ross

Choreography – Dustin Klein

Dramaturgy – Yvonne Gebauer

Chorus master – Ching-Lien Wu

Cast:

Aida – Ewa Płonka

Radames – Piotr Beczała

Amneris – Ève-Maud Hubeaux

Amonasro – Roman Burdenko

Ramfis – Alexander Köpeczi

The King – Krzysztof Bączyk

A Messenger – Manase Latu

High Priestess – Margarita Polonskaya