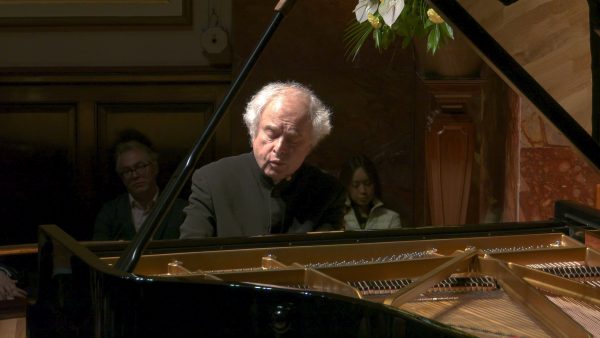

United Kingdom Schubert, Beethoven: Sir András Schiff (piano). Wigmore Hall, London 7.10.2025. (CSa)

United Kingdom Schubert, Beethoven: Sir András Schiff (piano). Wigmore Hall, London 7.10.2025. (CSa)

Schubert – Allegretto in C minor, D.915; Hungarian Melody in B minor, D.817; Drei Klavierstücke, D.946; Sonata in G major ‘Fantasie’, Op.7 D.894

Beethoven – Six Bagatelles, Op.126

Sir András Schiff likes nothing better than to bring mystery and spontaneity to his Wigmore Hall appearances. By keeping his unpublished programmes under wraps until the moment he announces them from the platform, he has taught his devoted followers always to expect the unexpected. His latest recital – a secret showcase full of interpretative insights and wry, self-deprecating commentary – shone a light on the musical relationship between Ludwig van Beethoven, and his spiritual disciple Franz Schubert in the final years of their lives. Both men resided in the same city – Vienna – and despite minimal personal contact, overlapped for nearly 30 years. The younger Schubert revered the older composer, absorbing the latter’s ground-breaking structures and innovative harmonies, and transmuting them into a lyrical and darkly introspective style of his own. It has often been said that Schubert, one of the torchbearers at Beethoven’s funeral, carried the metaphorical musical flame from the Classical tradition to the Romantic.

Almost as soon as Schiff stepped on the stage, bowed, pressed his palms together in front of his chest in his usual Namaste fashion, he took his place at the keyboard and without preamble, let the music unfold. A tense, slow and deeply expressive miniature march in the first section, magisterially played, suggested Beethoven. Yet a haunting lieder-like refrain in the second section sounded like Schubert at his most elegiac. By the time Schiff returned in reflective mood to the melancholy opening melody, there must have been some collective head-scratching in the Wigmore Hall. Beethoven or Schubert? That was the question. Was there a lifeline? It would have been pointless to ask the audience and too late to phone a friend. Schiff rose from the piano and mic in hand, quietly provided the answer. Schubert! We had been listening to his Allegretto in C minor, composed in April 1826, written just one month after Beethoven’s death and which some believe to be an expression of Schubert’s private mourning.

Schiff then informed us that the second item would be Beethoven’s last composition for piano, the third set of six Bagatelles. They were written between 1823 and 1824, while he was working on his Ninth Symphony and his late string quartets. ‘These might be bagatelles [trifles] by name, but they are great music nonetheless’, Schiff observed. He once described this set of miniatures as ‘late quartets in small form – intimate, radical and prophetic’. Played on this occasion with supreme authority, Schiff started serenely in the first Bagatelle before unleashing the full turbulence of Beethoven’s fantasy in the toccata-like Allegro. A radiant, almost hymn-like Andante was succeeded by a defiant and driven account of No.4 marked Presto, which, according to Schiff was the only piece Beethoven wrote in the fateful key of B minor. A playful rendition of the Quasi allegretto provided a light moment before a transcendent conclusion.

‘There is nothing Hungarian about Schubert’s Hungarian Melody in B minor’, quipped Schiff. ‘I happen to be Hungarian’ he added, ‘but then no-one is perfect!’ Despite his self-confessed shortcomings, Schiff’s rendition – all five minutes of it – was perfectly crafted and subtly modulated. Alternating between wistful, lyrical passages and rumbunctious gypsy-style dances, he captured what musicologist Harold Schonberg described as ‘a fragment of Hungarian sunlight filtered through Schubert’s Viennese melancholy’.

To round off the first half of the concert, Schiff chose Drei Klavierstücke D.946, written by Schubert in May 1828. These were the last three pieces he composed before his death in November of that year, at the age of 31. The first of the three, in E minor, was beautifully shaped, with passages of high drama punctuated by moments of deep serenity. No.2 in E major flowed like gently rippling water while No.3 in C major combined a cheerful rustic dance with interludes of dreamy melancholy.

The second half of the recital was taken up with one work: the great ‘Fantasie’ Sonata in G major, D.894. ‘It is so full of Waltzes and Ländler, it would be more appropriate to call it the dancing Sonata’, claimed Schiff, mischievously adding that ‘Schubert was a miserable dancer …and so am I’. Schiff has previously written that this luminous four-movement work, written in 1826, is ‘about silence – not as emptiness, but as the highest form of music. The opening measures are like a door to eternity’. Adopting a deliberately unhurried pace, Schiff gave the opening movement an almost timeless quality, while the Andante flowed calmly, a slow moving current of aqueous melody over a threatening undertow of anxiety. An elegant, dancing Menuetto tinged with sadness followed, giving way to a bright, rustic and ultimately serene Allegretto.

After an evening of unparalleled technical and artistic skill, demands for an encore seemed like an impertinence. Nonetheless, Schiff, having welcomed us with a sombre funeral march, sent us home with a spring in our step: not a Johann Strauss waltz but Schubert’s sprightly Grazer Galopp, D.925.

Chris Sallon

As someone also in the audience – and at my first live performance by Andras Schiff – I was spellbound by the man, his thoughtful interpretation of each of his surprise choices and his masterful command of the instrument and the Wigmore Hall’s acoustic. Christopher Sallon’s excellent review added that vital fourth dimension – describing what in music (as in other art forms) is to many of us, indescribable. Thank you, Christopher Sallon.