Switzerland Berlioz: Ann Hallenberg (Maria, mezzo-soprano), Andrew Staples (Narrator, tenor), Ashley Riches (Joseph, baritone), William Thomas (Herod, bass), Gareth Treseder (Centurion, tenor), Alex Ashworth (Polydorus/Father of the family, bass), Monteverdi Choir, Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich / Sir John Eliot Gardiner (conductor). Tonhalle, Zurich, 27.11.2021. (JR)

Switzerland Berlioz: Ann Hallenberg (Maria, mezzo-soprano), Andrew Staples (Narrator, tenor), Ashley Riches (Joseph, baritone), William Thomas (Herod, bass), Gareth Treseder (Centurion, tenor), Alex Ashworth (Polydorus/Father of the family, bass), Monteverdi Choir, Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich / Sir John Eliot Gardiner (conductor). Tonhalle, Zurich, 27.11.2021. (JR)

Berlioz – L’enfance du Christ, Op.25

There really is no other word for it: this was a beautiful performance of a beautiful work. If you are a fan of Berlioz’s wild, flamboyant works such as his Symphonie fantastique and La damnation de Faust, then, unless you know it, L’enfance du Christ will take you by surprise. Large orchestral forces are absent from this work, though Berlioz later added some brass to beef up the orchestral sound. It is one of the composer’s most uncharacteristic works.

The backstory is interesting. In 1830 the first performance of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique had caused an uproar, and in 1846 La damnation de Faust had only received tepid approval from the Parisian audience. In 1850 Berlioz needed a choral work to fill a concert programme, and the idea of a piece entitled L’enfance du Christ came to mind. Berlioz decided to play a trick on his audience, using a fictitious name as the seventeenth-century composer of the work; only afterwards did he uncover his deception and reveal his true identity. The first performance was a real success. Afterwards, one lady was heard to say ‘Monsieur Berlioz could not possibly have written anything as charming as that’. At a time when Berlioz’s music was viewed as wild and eccentric, the Parisians were enchanted by the work’s easy melodies and rather old-fashioned charm.

Berlioz was an agnostic; whilst the work is based on the biblical story of Christ’s birth (Berlioz wrote the words), it is not a religious work. The composition of L’enfance du Christ had begun when Berlioz sketched a few bars of organ music during a friend’s party in 1850. Later that year Berlioz turned the musical idea into L’adieux des bergers, a chorus of shepherds in Bethlehem bidding farewell to the child Jesus. Berlioz then expanded the piece into a three-part ninety minute oratorio a few years later. The work begins with a portrayal of King Herod, driven to villainy by his soothsayers, and the Massacre of the Innocents, prompting the second section depicting the flight of Joseph, Mary and Jesus into Egypt. The third section tells the story of the Holy Family’s stay in Egypt, with their bewildered arrival in the town of Sais and finally their welcome in the house of an Ishmaelite family.

The work quickly gained admirers, including the 12-year-old Massenet, and Brahms, who wrote to Clara Schumann: ‘This work has always enchanted me. I really like it, the best of all Berlioz’s works.’ Even Debussy, indifferent to the composer’s works, regarded it as a masterpiece.

Sir John Eliot Gardiner had assembled a fine line of soloists, none of them French: Swedish mezzo Ann Hallenberg made her name in Zurich in 2003 when she jumped in for an indisposed Cecilia Bartoli in a Handel opera; she is now perhaps best known for her Handel interpretations. I am not sure this work really suited her particular talents, her French diction rather woolly, though she sang very well.

British Tenor Andrew Staples, singing the central role of the Narrator is no stranger to audiences in Britain and his voice was perfect for the role.

British baritone Ashley Riches is also a well-known name; from my seat in the balcony, he was often overshadowed in terms of volume by Hallenberg and the orchestra.

British bass William Thomas was a new name to me; still only 23 years old, his deep, rich bass was a real discovery. Berlioz paints Herod in a sympathetic light, tortured in his dreams that he will probably be usurped by an infant. ‘O misère des rois!’ was given an excellent rendition.

Gareth Treseder, a former apprentice with the choir, and Alex Ashworth, a mentor on the choir’s apprenticeship scheme, sang the minor roles with utmost distinction.

The singing of the distinguished 35-strong Monteverdi Choir never fails to impress, in all registers; they really are among the cream of the British choral tradition and one could just sit back and wallow in their sound. The celestial sopranos, as heavenly angels, singing offstage, were a particular delight, as was the whole choir in the well-known chorale ‘Choeur des Bergers’. To close the work on an ethereal note, the choir sings a cappella ‘O mon âme, pour toi reste-t-il à faire’, most affecting.

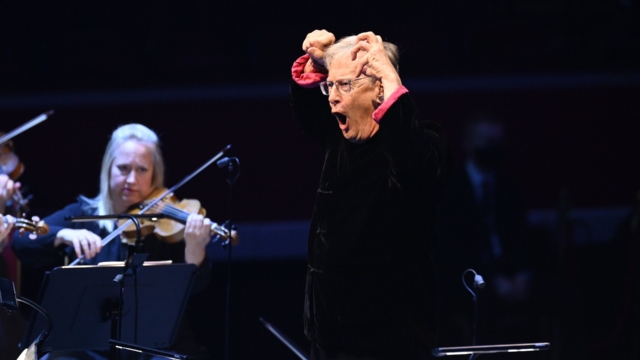

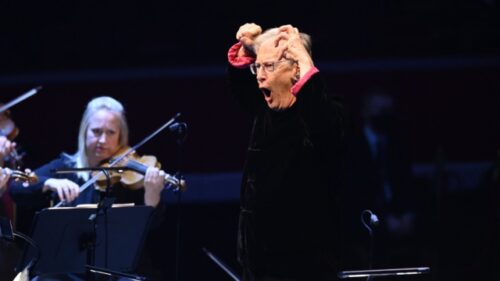

Sir John, in a pre-concert interview with the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, explained that he coaxed the Tonhalle Orchestra to play in the French style, with transparent orchestral colouring. He succeeded in that venture; the orchestra are certainly versatile. Sir John, best known for his Bach interpretations, is clearly an admirer of Berlioz; his conducting was ever delicate and full of grace, and his love of the piece shone through at every turn.

There were several fine orchestral interludes. The woodwind, in particular, impressed across the board. Towards the end of the piece, a lengthy trio consisting of two flutes and harp was a ravishing highlight – thanks to principal flutist Sabine Poyé Morel, colleague Hanna Lübcke and harpist Sarah Verrue.

Sir John and the Monteverdi Choir now bring the piece back to Britain for two performances: on 10 December in Ely Cathedral and 11 December at St. Martin-in-the-Fields. Then to the Palau de la Música in Barcelona on 16 December. Do catch it if you possibly can. If you do not know this quietly emotional work, it is a revelation.

John Rhodes