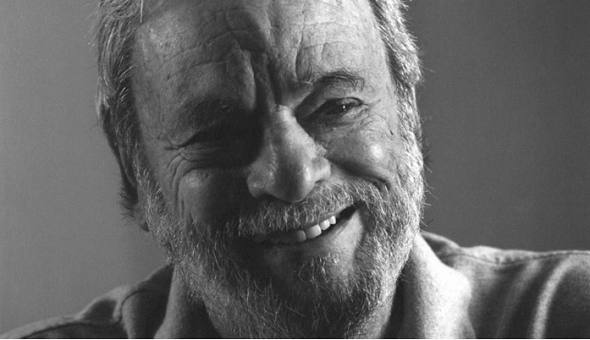

Stephen Sondheim’s self-reverential Here We Are

Composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim notoriously resisted the idea that his musicals were operas. He would recoil at any comparison between his score for Here We Are, the show he was still tweaking at his death two years ago, and Verdi’s for Falstaff, but it keeps nagging at me.

I am not the only opera lover who might argue that Sweeney Todd, Sunday in the Park with George and Passion are obviously operatic. Here We Are, however, decidedly is not. It is a musical, though hardly an ordinary one. What the music shares with Falstaff is that so much of it is self-referential. Both Verdi and Sondheim mock themselves – and us – by peppering the score with references to their earlier works.

As a longtime admirer of Sondheim’s music as well as his incomparable lyrics, I made it a point to see the show, which opened in October in a limited, off-Broadway run at The Shed in New York.

Theatre critics appreciated the taut book by David Ives, which fits together a first act based on The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie with a second act on The Exterminating Angel, two 1960s absurdist, darkly comic films by the director Luis Buñuel. Both the films and the show skewer the rich and powerful, who find themselves helpless when the tables are turned. In the play, circumstances thwart a merry band of privileged New Yorkers in their serial efforts to eat brunch; the group ends up dining in a diplomat’s posh home, which they are mysteriously unable to leave.

Two months into the run, a Google search still finds no commentary of any depth on the music, That is too bad, because the score is extraordinary on several levels, not least because so many moments feel oddly familiar. Not quite direct quotations, they still call to mind elements of Sondheim’s previous musicals.

When reviews noted this, they wrote it off as Sondheim being Sondheim. And yes, musical-theater composers employ favorite compositional tropes almost reflexively. Puccini liked to swell the music on climaxes a certain way that is instantly identifiable (and which Andrew Lloyd Webber stole shamelessly). Gershwin had favorite jazz-like licks that found their way into his music. Wagner employed his own rhythms and harmonic sonorities which amounted to all-purpose signatures.

Both Sondheim and Verdi excel at finding musical gestures that fit the words and the scenes they were written for, expanding these musical descriptions in the moment. Halfway through Act I, though, it dawned on me that Sondheim was intentionally parodying himself, persistently looking back. And it was just those connections that tantalized me the most about Sondheim’s references.

Alas, Sondheim’s score is not available to study, nor is there (yet) an official, original-cast recording to listen to. I did, however, get my hands on a copy of the script, and a pirated recording to match up at least some of these connections. A friend who knows Sondheim’s less-popular works far more thoroughly than I do called them ‘echoes of all his previous compositions scrambled into a soufflé’. When I asked him which ones, he said, ‘all of them’, and mentioned several such lesser-known works such as Assassins, Merrily We Roll Along, Evening Primrose and Road Show.

Verdi quoted virtually every one of his theatrical works in Falstaff, and I think Sondheim did here too.

As one example, several leading theatre critics homed in on this delicious lyric: ‘We do expect a little latte later, But we haven’t got a lotta latte now’. But my ear perked up at a later point in the same song, when the music for these lines from the waiter’s song – ‘Right, who had the duck? You’re out of luck’ – called to mind the satirical ‘A Little Priest’ from Sweeney Todd. Full points for anyone who recognizes that ‘A Little Priest’ was about how the flavors of the pies Mrs. Lovett made from Sweeney’s murder victims vary according to the occupations of the deceased. Also, Sweeney is about the downtrodden getting revenge on the wealthy, a key aspect of Here We Are.

A torch song later in Act I, sung by the surviving spouse of a murdered chef, sets the lyric ‘Sometimes you want too much, Too soon – And then it’s too late’ to music reminiscent of the anthem ‘I’m still here’ from Follies, which was sung by a trouper recounting travails she overcame to survive.

Arguably, the new musical’s best-crafted number is a duet for a politically radical, sexually ambiguous teenager hopelessly lovestruck by a handsome young army officer. In it I heard an almost identical melody and rhythm from ‘On the Steps of the Palace’, Cinderella’s song as she leaves the ball in Into the Woods. That makes perfect sense, as both characters are at a crossroads, having to decide which direction to take in life.

Music resembling a line sung by Dot, the artist Seurat’s muse in Sunday in the Park With George, infuses phrases sung by Marianne, the blond bombshell wife of a wealthy blowhard as she appreciates the poshness of the diplomat’s dining room: ‘Blessed with this – Blessed with these – All this beauty that is ours’. A few minutes later, as the soldier fixates on the teenage radical, Sondheim’s underscore borrows from the vamp that precedes the choral hymn ‘Sunday’. Not only does it call to mind a moment of beauty as the painting comes together in real time on stage, it aptly connects women who both entrance and inspire men.

Verdi’s score for Falstaff teems with such telling, if self-mocking, moments. When the women describe the fat night’s heftiness, they sing ‘Falstaff immenso’ to the same music as the phrase ‘immenso Ptah’ in Aida, and the orchestra swells. When Falstaff thinks he is going to have an assignation he puffs himself up with a light-footed arietta, introduced with music from Iago’s ‘Credo’ in Otello.

These details amplify the message of Falstaff – that we can all be mocked (as the title character sings in the choral fugue that ends the opera). In Sondheim’s piece, the privileged socialites who set out for brunch in Act I cannot escape their own selves in Act II, trapped in decaying luxury as the world explodes around them. With these fleeting musical self-references, both composers remind us all that we often can’t help doing the same thing even when we know better.

In Joe Mantello’s inventive production, lots of mirrors around a thrust stage remind us that we are in some ways characters out of Buñuel’s absurdist films. In the cast, Bobby Cannavale bosses around a herd of self-satisfied A-listers in search of brunch, among them Rachel Bay Jones as a wife who’s smarter than she looks. David Hyde Pierce, with impeccable timing and phrasing, embodies a louche, piano-playing bishop who has an insatiable foot fetish. Veteran actors Tracie Benett and Denis O’Hare contribute all-purpose roles as servants, maids or waiters.

The music benefits from Sondheim’s longtime orchestrator, Jonathan Tunick, and conductor Alexander Gemignani, who put the finishing touches on this score. He is the son of Paul Gemignani, who conducted most of Sondheim’s most prominent musicals, from A Little Night Music to Sunday in the Park with George.

The show is scheduled to run in New York through 21 January.

Harvey Steiman