Austria Puccini, Turandot: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Vienna State Opera / Marco Armiliato (conductor). Filmed at the Vienna State Opera (directed by Tiziano Mancini) on 16.12.2023 and currently available on medici.tv. (JPr)

Austria Puccini, Turandot: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Vienna State Opera / Marco Armiliato (conductor). Filmed at the Vienna State Opera (directed by Tiziano Mancini) on 16.12.2023 and currently available on medici.tv. (JPr)

When Claus Guth’s new Regietheater Turandot premiered at Vienna State Opera in December last year I understand it was well received by an audience who used to be, back in the day, so very conservative. There was nothing Chinese about it all and turning everything into a psychodrama focussing – in Freud’s Vienna – on a young woman’s irrational fear of intimacy and sex, may avoid cultural appropriation though it does diminish the opera’s epic grandeur. Fundamentally, the moral of Turandot is unaffected by all the head-scratching Guth’s Konzept induces with true love winning through in the end thawing even the coldest, and most brutal, of hearts. That Turandot is a flesh-and-blood woman with human fears and desires and not an ice princess is nothing really new. To be truthful when left alone at end for an extended (more of that later) love duet Guth’s staging worked best as Turandot melted (!) into Calaf’s arms.

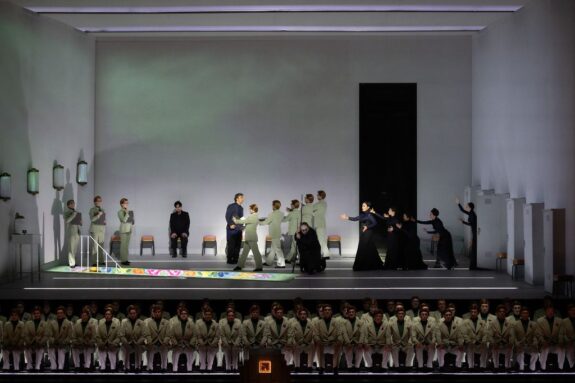

Before the opera proper begins there is the ticking of a clock heard and the hands of the clock (ever present?) on the prompt box go fast-forward. What happened from then on I cannot be certain but at the very end of the opera, the hands which had stopped at 12 start turning again. We are welcomed into a uniform, somewhat faceless, society inhabiting Etienne Pluss’s set – a white box – that fills the entire stage. Everyone is in costume designer Ursula Kudrna’s lime green suits, have red hair, glasses and roses on their lapels. The chorus (almost as in COVID-19 days) is marginalised, forming two rows at the very front of the stage in Act I and offstage in Act II apart from the children’s chorus of mini-mes.

The chorus are sitting on storage boxes (each possibly containing the head of one of Turandot’s past suitors like others clearly do). Characters enter from below the stage with more boxes or enter through some metal lockers. While they can come on the stage, Calaf (wearing an odd-looking modern suit) has climbed into the white box but is now trapped and cannot get out. It is a highly bureaucratic society, heads must be measured, forms filled out and the sharpness of the executioner’s sword tested on a large pumpkin. On the back wall video of a large ghostly image of Turandot from time to time haunts what we see, smearing blood when the blindfolded Prince of Persia is taken out to return as a headless corpse. Timur is traditionally blind with a staff, but an austerely dressed Liù has an entourage of four who are costumed like her and form a conga line as she enters to sing ‘Signore, ascolta!’. Together they all try and entrap Calaf in a cat’s cradle of ribbons before he breaks free and summons Turandot by slapping the huge doors to the rear of the stage, no gong of course!

Chief amongst those bureaucrats we saw earlier are Ping, Pang and Pong who begin the second act – in what might be a changing room – dreamily reminiscing and, for some reason, removing their wigs and glasses and stripping down to vests and trousers. After playing with the decapitated heads they brought on in boxes they exit through a locker and soon we are back in the large box-like room, now a bedroom beyond those first-act doors. A cowering Turandot with her long white hair lies on a bed in a satin negligee with four masked Barbie doll-like figures in pink at the end of it. Also present is the hooded executioner Pu-Tin-Pao. Emperor Altoum enters wearing a pink regalia sash, is grey-haired, clearly ailing, and needs a walking stick. From a chest under the bed the relics of Turandot’s raped and murdered ancestor Lo-u-Ling – her limb bones – are displayed. Turandot is put into a white bridal gown with feathered skirt before revealing the first of the three riddles she clearly believes will save her from a similar fate. Turandot’s world begins to turn upside down, beginning with her bed, and as Calaf is triumphant she ends the act embraced by her Barbies.

The final act takes place on two levels: below Turandot is in an upright bed having nightmares surrounded by the four pink doppelgängers wielding knives and above is the room from Act I with the lockers and stools overturned, lights torn down from the walls, and people wandering aimlessly about. Calaf is tempted by a Turandot lookalike, gold bars and a bemedalled figure before below a bloodied and roughed-up Liù is dragged on. It is Turandot herself who begins to further torture Liù, wrapping her legs around her at one point before retreating under the cover of her bed as Liù finds a knife to commit hara-kiri. After having rose petals scattered on her dead body Liù is wrapped in a black shroud and dragged off.

A wall comes down isolating Turandot and Calaf at the front of the stage, they kiss before she brandishes a knife threateningly and they kiss again. The wall lifts and the chorus are back sitting around on their boxes. Turandot is put back in her wedding gown and both she and Calaf are given sashes and are sat far apart centre stage. At the very end Turandot rebels and rejects the rigid, formal society, removes her sash and then Calaf’s before running out with him through a locker.

Puccini had struggled with Turandot for almost five years and by early 1924 eventually everything had been orchestrated up until Liù’s death. The final scene in which Calaf’s kiss transforms Turandot into a warm-hearted, loving human being was left only as sketches. Unfortunately, on November 29, 1924, the chain-smoking Puccini died in Brussels the day after a cancer operation. Franco Alfano completed the opera from Puccini’s sketches, but this did not satisfy Arturo Toscanini who conducted the first Turandots. Jonas Kaufmann recorded the entire Alfano completion in 2022 for Sir Antonio Pappano and Warner Classics and here he was singing it in his role debut in Vienna. Have I heard it before, I cannot be sure, but it made me long for the truncated version we usually hear. The extra bars now remind me more – perhaps not surprisingly? – of Sir Andrew Lloyd Webber than Puccini and are not appropriate for the concluding Siegfried-like love duet I suspect Puccini envisaged.

Conductor Marco Armiliato can do little wrong in Puccini and although he did stretch some tempos to indulge one or more of his singers it had all the necessary drama, sweep and passion. And, as also to be the expected, the Vienna chorus and orchestra were excellent. Jonas Kaufmann sounded fresher as Calaf in late 2023 than I had heard him of late. It goes without saying that his tenor voice is baritonal but top notes were solid’; ‘Nessun dorma’ was the showstopper it must be, and his acting was assured. Asmik Grigorian – a soprano David Mellor in a very recent CD review astonishingly claimed he had never heard of – was remarkable in her own role debut as Turandot. Always the most compelling of actors, Grigorian’s Turandot was a real woman and not some fantasy figure and her impressive voice allowed her to sing the role – including ‘In questa reggia’ – with uncommon ease. Was it Guth who wanted such an intense and forthright Liù with Kristina Mkhitaryan seemingly auditioning to sing Turandot in the future. Dan Paul Dumitrescu was a rather gruff Timur, Jörg Schneider gave Altoum some poignancy while Martin Hässler’s lyrically sung Ping stood out among the trio of ministers.

Jim Pritchard

Creatives:

Stage director – Claus Guth

Set designer – Etienne Pluss

Costume designer – Ursula Kudrna

Lighting designer – Olaf Freese

Video designer- Roland Horvath (ROCAFILM)

Choreography – Sommer Ulrickson

Dramaturgy – Konrad Kuhn, Nikolaus Stenitzer

Chorus master – Thomas Lang

Cast:

Turandot – Asmik Grigorian

Altoum – Jörg Schneider

Timur – Dan Paul Dumitrescu

Calaf – Jonas Kaufmann

Liù – Kristina Mkhitaryan

A Mandarin – Attila Mokus

Ping – Martin Hässler

Pang – Norbert Ernst

Pong – Hiroshi Amako

First balcony lady – Antigoni Chalkia

Second balcony lady – Lucilla Graham

Voice of the Persian Prince – Jörg Schneider

Ballet – Europaballett St. Pölten