United States Mazzoli, Breaking the Waves: Soloists, Chorus, and Orchestra of Opera Philadelphia/Steven Osgood (conductor), Perelman Theater, Kimmel Center, Philadelphia. 24.9.2016. (BJ)

United States Mazzoli, Breaking the Waves: Soloists, Chorus, and Orchestra of Opera Philadelphia/Steven Osgood (conductor), Perelman Theater, Kimmel Center, Philadelphia. 24.9.2016. (BJ)

Cast:

Bess McNeill–Kiera Duffy

Jan Nyman–John Moore

Dodo McNeill–Eve Gigliotti

Bess’s Mother–Patricia Schuman

Dr. Richardson–David Portillo

Terry-Zachary James

Minister–Marcus DeLoach

Sadistic Sailor–John David Miles

The Runt–George Ross Somerville

The Stone Thrower–Daniel Taylor

Production:

Director–James Darrah

Scenic designer–Adam Rigg

Costume designer–Christi Karvonides

Projection designer–Adam Larsen

Lighting designer–Pablo Santiago

Wig & Make-up designer–David Zimmerman

Chorus Master–Elizabeth Braden

Stage Manager–Becki Smith

Dramaturgs–Mike Cohen, Cori Ellison

A mere few months after presenting the East Coast premiere of Jennifer Higdon’s Cold Mountain, the irrepressibly enterprising Opera Philadelphia staged the world premiere of Breaking the Waves, an opera based on Lars von Trier’s 1996 film of the same title, and co-commissioned by the company (with Beth Morrison Projects) from composer Missy Mazzoli and librettist Royce Vavrek.

To say that the result was something of a triumph would be something of an understatement. Building with a sure hand on Vavrek’s lucid libretto, which makes few changes or additions to the movie’s screenplay by von Trier and Peter Asmussen, the 35-year-old composer, born in nearby Lansdale, has created a work of often luminous beauty and moving insight into the power of love and the torments inflicted on it by societal pressures.

There was little trace in the score of the indie-rock influences that have been attributed to Mazzoli’s music. In this work, the first of hers that I have encountered, she speaks a predominantly tonal language of remarkable contemporary-classical purity. The vocal writing is unfailingly grateful for the singers, and the treatment of the chamber-sized score is at once incisive and, especially as regards the upper woodwind parts, full of beautiful and atmospheric touches. My only (minor) reservation stemmed from a feeling that the piece could have benefitted from a little more variety of pace: slow music, with final syllables frequently extended, prevailed through much of the score, most of the more propulsive writing being located in some crisp choral utterances.

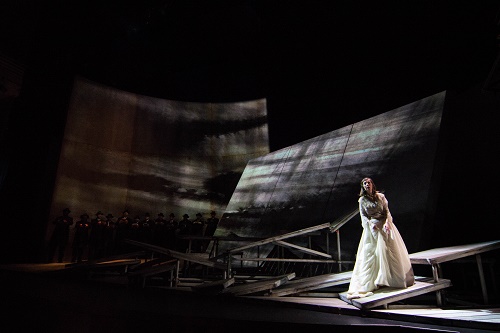

The skillful production by James Darrah was graced with an essentially abstract set by Adam Rigg—the grouping of Calvinist worshipers that first greeted the eye made a tremendous effect under Pablo Santiago’s unfailingly well-judged lighting—and Christi Karvonides’s costumes were equally unfussy and appropriate. Supported by assured conducting from Steven Osgood and accomplished contributions from the orchestra and Elizabeth Braden’s chorus, the soloists constituted a veritable dream cast.

John Moore was both virile and sensitive as the oil-rig worker Jan Nyman, the “outsider” who comes into this close-knit–too close-knit–Scottish community to marry Bess McNeill. Eve Gigliotti was vocally and dramatically excellent as Beth’s sister-in-law, Dodo. As Bess’s mother, Dr. Richardson, Jan’s friend Terry, the minister, and a sadistic sailor, Patricia Schuman, David Portillo, Zachary James, Marcus DeLoach, and John David Miles all provided thoroughly convincing portrayals.

And positively shining at the head of this splendid ensemble was Kiera Duffy’s Bess, lovely both to listen to and to look at, and heartbreaking in the eventual decline and death brought on her by the religious fanaticism of her community, and the delusions wished on her by her husband after he is paralyzed in an accident on the rig. That accident was the only element of the action that the director had not devised a compelling way to stage. But no matter: this was only a momentary disappointment in an overwhelmingly cogent and affecting presentation of a work worthy to stand alongside Bernard Rands’s Vincent at the very summit of 21st-century American operatic achievement to date.

Bernard Jacobson