United Kingdom Schumann, Widmann, Mozart: Jörg Widmann (clarinet), Tabea Zimmermann (viola), Dénes Várjon (piano), Wigmore Hall, London, 4.1.2018. (CC)

United Kingdom Schumann, Widmann, Mozart: Jörg Widmann (clarinet), Tabea Zimmermann (viola), Dénes Várjon (piano), Wigmore Hall, London, 4.1.2018. (CC)

Schumann – Märchenerzählungen, Op.132; Märchenbilder Op.113

Widmann – Es war einmal … (Fünf Stücke im Märchenton) (UK premiere); Fantasie

Mozart – Clarinet Trio in E flat, K498, ‘Kegelstatt’

The first concert of Jörg Widmann’s residency at Wigmore Hall, this was a supreme example of inspired programming and a wonderful way to introduce several facets of Widmann’s activities (he also conducts).

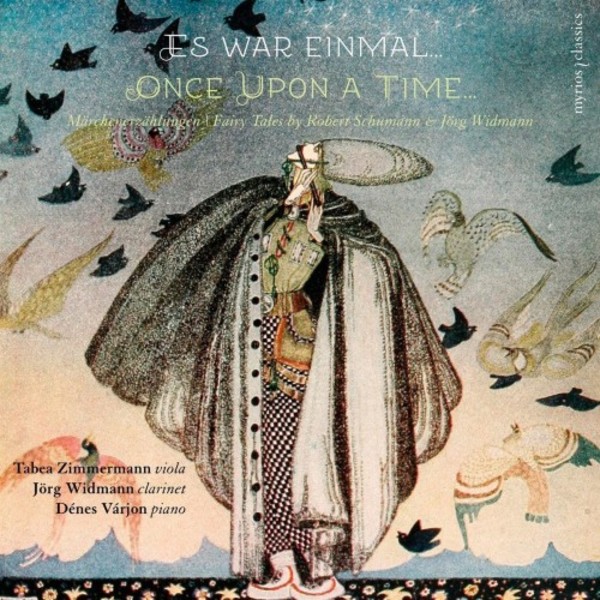

The more substantial of Widmann’s own works here was Es war einmal (‘Once Upon a Time’: readers may also be familiar with Zemlinsky’s splendid opera of this name). ‘Es war einmal’ is also the name of the Myrios CD (which, strangely, I did not see on sale in the foyer) upon which the Wigmore programme was based: the two share Widmann’s Es war einmal and Schumann’s Märchenerzählungen, Op.132 and Märchenbilder Op.113. His Fantasiestücke Op.73 was replaced by more Widmann: Fantasie for solo clarinet.

One could easily argue that the world at this time needs more fantasy; for Widmann, though, there is another layer. He states that ‘fairy tales were … a source of unrest for me as a seismograph of mankind’s underlying primal fears and desires’. His piece offers ‘a naïve and fantastical alternative concept to our genuine world with all its upheavals’. Whether Schumann thought in similar terms is debatable, although for Romantic composers the fairy realm seemed to be as varied and, often, as frightening as the so-called ‘real world’. (To explore the world of fairy tale in more psychological depth, try Marina Warner’s excellent little book, strangely enough also entitled Once Upon a Time: link).

Schumann’s Op.132 is scored for clarinet, viola and piano and so makes a perfect partner for Widmann’s piece. The notes for the Myrios release state that ‘Schumann probably knew Mozart’s “Kegelstatt Trio”, composed for the same group of instruments’; the Wigmore notes point out that Clara Schumann had performed the Mozart in January 1851, just a couple of years before her husband’s piece was written. Luxury, here, to have one of the world’s leading violists, Tabea Zimmermann, as one of the group. Zimmermann was placed nearest to the piano keyboard; Widmann parallel and towards the end of the piano. The sense of chamber music at its finest was near palpable, as phrases echoed between the viola and the clarinet. Zimmermann felt a stronger presence than on the disc, at least from the back of the hall. While there was the occasional moment in this first piece when one felt Widmann might have been experiencing problems with his instrument, this remained a hugely intimate, nuanced performance. Only Várjon’s contribution felt a touch anonymous in comparison with the two huge musical personalities onstage.

Curiously, the programme opted not to list the names of the five movements of Es war einmal … (they are ‘Es war einmal …’; ‘Fata Morgana’; ‘Die Eishöhle’; ‘Von Mädchen und Prinzen’ and ‘Und wenn sie nicht gestorben sind’). No doubting the early viola line’s debt to Romantic music; this very act of reference itself was significant as it set up a precedent in which Widmann could zoom in and out of a Romantic soundworld and back into his own. And ‘his own’ includes the violist using the back of her instrument as a sound generator, the clarinet playing inside the piano to activate piano string harmonics and a variety of instructions for the pianist. All of this, if it takes us into a a fairy tale world, take us into a rather nightmarish one. It is as if, at times, Schumann’s music had been distorted through a fairground mirror.

More Widmann after the interval, in his 1993 Fantasie for solo clarinet, a piece that draws on jazz, klezmer and dance music. It begins with a multiphonic, a daring way to begin, but this is after all a virtuoso piece Widmann wrote for himself to play. Widmann’s own performance opening was perfectly judged (Eduard Brunner’s performance on Naxos is launched by a rather ugly sound, in contrast). Virtuoso, comedic, characterful, Widman’s was a simply beautiful performance. The composer himself admits a debt to the commedia dell’arte, and that aspect came through strongly on this occasion.

Schumann’s Op.113 Märchenbilder for viola and piano once more plumbs the emotional depths, particularly in the two central movements (there are four in total). Tabea Zimmermann’s performance found her viola in full cantabile mode for warm-toned long lines which really did have a near-vocal element to them, while in the more robust rhythms of the ‘Lebhaft,’ both her and Várjon exuded considerable energy. Zimmermann was positively astonishing in sheer velocity and accuracy in the third movement (‘Rasch’) before the finale (‘Langsam, mit melancholischm Ausdruck’) acted as a magical lullaby, Zimmermann wondrously mellow of tone.

Finally, Mozart, the charming, flowing ‘Kegelstatt’ Trio. While Várjon’s contributions seemed rather anonymous in comparison with those of Zimmermann and Widmann, this was a lovely performance nevertheless. The finale holds a famous viola solo, delivered simply gloriously here. The effect of hearing this at the end was simply a reminder that all roads, on some level, lead to Mozart so we can be reminded of his heavenly genius.

An encore nearly didn’t happen (the applause was petering out, audience members on their way out) – but it did. A nice touch that the Wigmore notes for the Mozart refer to other works for this combination, one by Kurtág (the Hommage à R. Sch.) and the other by Bruch (Eight Pieces, Op.83), and it was to Bruch that they turned for that encore. Bruch’s Op.83 Pieces were composed in Berlin in 1910. We were offered No.6, ‘Nachtgesang’ (Nocturne) a fitting farewell, tenderly delivered. Just as one hopes that attendees (and, indeed, readers of this review) might be inspired to follow up the main body of the programme with the related Myrios Classics release (MYR020CD), perhaps some might explore the whole of Bruch’s Op.83?.

Colin Clarke