United Kingdom Henze, Phaedra: Soloists, Southbank Sinfonia / Edmund Whitehead (conductor), Linbury Theatre, Royal Opera House, London, 16.5.2019. (MB)

United Kingdom Henze, Phaedra: Soloists, Southbank Sinfonia / Edmund Whitehead (conductor), Linbury Theatre, Royal Opera House, London, 16.5.2019. (MB)

Production:

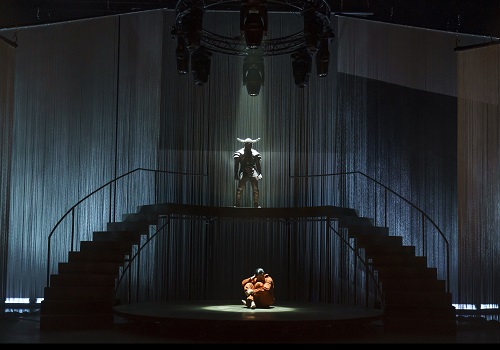

Director – Noa Naamat

Lighting designer – Lee Curran

Designer – takis

Cast:

Phaedra – Hongni Wu

Hippolyt – Filipe Manu

Aphrodite – Jacquelyn Stucker

Artemis – Patrick Terry

Minotaurus – Michael Mofidian

Hans Werner Henze’s penultimate opera, Phaedra has been fortunate indeed in London since its 2007 Berlin premiere. Astonishingly, this was the third time I had seen the work in London: first a Barbican concert performance; then the Guildhall’s excellent double-bill, coupled with the early radio opera, Ein Landarzt; now a staging at the Royal Opera’s Linbury Theatre, from members and one soon-to-be-member of its Jette Parker Young Artists Programme and the Southbank Sinfonia.

I continue to find it an elusive, even enigmatic work, difficult to pin down – as often with Henze. There is nothing wrong with that, quite the contrary. Immediately obvious works that have little to reveal on subsequent encounters – Tosca, for instance, whatever its qualities – are not the most interesting. Layering of its libretto, by Christian Lehnert, is, for me at least, a little too self-conscious, indeed in that sense itself obvious; that of the score, however, continues to fascinate, both in itself and with respect to Henze’s lengthy career and well-nigh unmanageable œuvre. Conductor Edward Whitehead and the Southbank Sinfonia proved strong in their communication of the score’s textural layering, Schoenberg, Berg, Mahler, and Wagner lying behind or, perhaps better, beneath it, the orchestra’s lines seemingly summoned up like a refined Götterdämmerung oracle. I was put in mind of a remark by Henze from four decades earlier, from an interview with Die Welt given to coincide with the premiere of The Bassarids: ‘The road from Tristan to Mahler and Schoenberg is far from finished, and … I have tried to go further along it.’

Henze’s way was always, or usually, though, then to take up another path thereafter, perhaps resuming that earlier path some time later. We perhaps view his way with greater clarity now, or kid ourselves that we do. At any rate, other tendencies shone through too: Weill-like (Hindemith too?) wind and percussion; mesmerising saxophone lines that lured one seemingly to nowhere (a re-imagining of Natascha Ungeheuer?); magical forest colours (König Hirsch); and, perhaps most tellingly, towards the close, when Hippolyt surprisingly, disconcertingly returns as Virbius, the transformational magic of Ariadne auf Naxos, Straussian reference clear, but kinship to Hofmannsthal’s ideas (perhaps via Elegy for Young Lovers) ultimately more meaningful. At its best, Noa Naamat’s staging seemed to take its leave from these circles, lines, interactions of musical and aesthetic meaning, a sense of eastern ritual (perhaps a little Robert Wilson, but less formulaic than his work has become) coming into contact and conflict with turning of the wheel. Comparison and contrast with the work of Birtwistle came to mind, as they had on my previous encounters with the work.

The singers all proved excellent. Though the work is called Phaedra, I do wonder whether Henze would have been better lending Hippolyt(us)’s name to it. (But then, arguably, Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie is similarly misnamed.) Filipe Manu, due to join the JPYAP next year, proved compelling indeed in the would-be title role, as vulnerable an object of contemplation and, later, as equivocal a vehicle of reinvention as Henze’s earlier Prince of Homburg. Was Hongni Wu’s Phaedra presented too vampishly in this production (not necessarily in performance)? Perhaps, but the deepening of her range of vocal colour throughout the evening offered compensation. Jacquelyn Stucker and Patrick Terry (the programme’s first countertenor) offered strong, detailed performances as Aphrodite and Artemis, whilst Michael Mofidian’s Minotaurus, richly sonorous yet equally careful of detail, left one wishing greedily that he had had more to sing, his persistent stage presence notwithstanding.

Why, then, did I emerge feeling slightly dissatisfied – or perhaps wondering whether I should have done? It may just have been a matter of how I was feeling on the day: it happens to us all. I do not think, though, that it was just that. Did the decision to introduce an interval get in the way? I think it did, making the work seem longer, more drawn out, more sectional than it is. I am not sure that the parameters within which Naamat’s staging had to operate helped in that respect. Though necessarily simple in scenic terms, it paradoxically seemed to dart around somewhat from scene to scene, perhaps through no fault of its own somewhat blunting the underlying ritual power of the score. Perhaps, alternatively, that was actually a reflection of the fragmentary qualities of the opera, of Hippolyt’s partial, flawed regaining of consciousness under his new identity. If I continue to find Phaedra enigmatic, Henze’s genre designation of ‘concert opera’ included, then that will doubtless say something about it, me, the performance, the production, or about any combination of the above. Such, after all, is opera.

Mark Berry