Czech Republic Beethoven, Fidelio: Soloists, Orchestra and Chorus of the Prague State Opera / Karl-Heinz Steffens (conductor), Prague State Opera, 9.1.2020. (SS)

Czech Republic Beethoven, Fidelio: Soloists, Orchestra and Chorus of the Prague State Opera / Karl-Heinz Steffens (conductor), Prague State Opera, 9.1.2020. (SS)

Production:

Director – Vera Nemirova

Sets and Costumes – Ulrike Kunze

Chorus master – Alfred Melichar

Dramaturgy – Sonja Nemirova, Jitka Slavíková

Cast:

Leonore – Erika Sunnegårdh

Florestan – David Butt Philip

Don Pizzaro – Martin Winkler

Marzelline – Vera Talerko

Rocco – Zdeněk Plech

Jaquino – Thorbjørn Gulbrandsøy

Don Fernando – Paul Armin Edelmann

First prisoner – Zdeněk Haas

Second prisoner – Alexander Laptěv

After three years of renovation work, the Prague State Opera reopened its doors on 5 January with a gala concert held on the same date as its inaugural performance 132 years ago. The first opera in the refurbished house followed a few days later with Fidelio, a traditional favorite for (re-)inaugurating lyric stages and on this occasion also an early bird instance of Beethoven anniversary programming. It wasn’t an opening night, with Vera Nemirova’s production having already premiered in 2018, but the director returned to rehearse a new cast for this run and took a curtain call, making the event feel properly festive.

The performance itself satisfyingly measured up to the big occasion, beginning encouragingly and growing in strength right up to the euphoric finale. The State Opera musicians had some negligible moments of choppiness but otherwise gave one of the most committed orchestral performances of the week, and Karl-Heinz Steffens’s conducting was nicely kapellmeisterisch: tempi in Fidelio can be a problem, especially in numbers like ‘O namenlose Freude’, but were ideal here; lively, but never too frenetic.

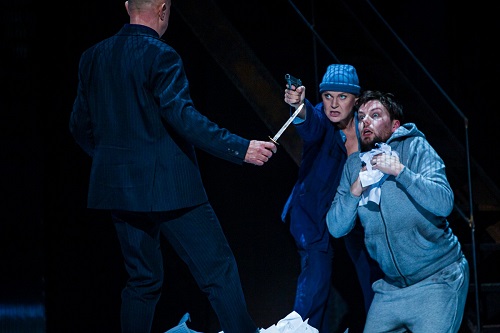

Both the direction and the performances enacted a vast temperamental gulf between the prison’s comprised management and its lowly employees, with Zdeněk Plech, Vera Talerko and Thorbjørn Gulbrandsøy constituting the most wholesome trio I have seen as Rocco, Marzelline and Jaquino. Talerko sang Marzelline very attractively and was so empathetic in the role that she barely seemed to hurt Jaquino’s feelings, while Plech’s Rocco was a likable lug whose voice carried well despite the docile portrayal. Martin Winkler, on the other hand, delivered every phrase with a snarl as a blackly despotic Pizarro. Winkler was a spot of luxury casting in this production: it is always a treat to hear his gravelly, dark-hued baritone and he’s one of the biggest chameleons working in opera, an enormously gifted character actor who can play brutes, comic buffoons, villains, oddballs, campy extroverts, melancholic brooders – anything you throw at him, he inhabits it completely.

Erika Sunnegårdh showed intense single-mindedness as Leonore but also frequently receded into the background; in the logic of this staging, she only has one reason for hanging around Rocco and Marzelline, and isn’t interested in being part of their group. Deepened by Sunnegårdh’s forceful singing, this characterization then flowed into Nemirova’s take on the finale, which is that Leonore’s drive is less resolved by the reunion with Florestan than shattered into tiny shards. This is not the first production to juxtapose or even subvert the exuberant, overblown character of Fidelio with the image of two broken people who have no realistic hope of a full recovery. But it seems cynical to do this as a superficially naturalistic twist on the characters, with no deeper message than to glibly remind us that heroic Beethovenland is a psychologically simplistic place. Making Leonore grittily ‘relatable’ in this way felt like an erasure of one of the most radical female characters in the operatic canon. The default role of women in opera is to suffer, sacrifice themselves, and in so many cases, to die horrible deaths. Leonore, however, takes charge, does extraordinary things, and gets recognized for them. Why undermine her heroism and her triumph?

The naturalism continued with a catatonic Florestan affected by PTSD, though this wasn’t as overly insensitive as it might have been (naturalism bluntly brought to bear on mental illness is one dubious trope of British theater that I don’t miss). David Butt Philip’s acting was strikingly subtle and his singing a revelation. Most English tenors sound to me like adenoidal aliens, which sounds mean, but many of them do pick up a reedy or pale timbre and peculiar vocal mannerisms from Oxbridge college choirs. Butt Philip was actually born in an English cathedral city and began singing in another English cathedral city, yet has a healthy and vivid sound that shows little trace of this background. Moreover, his German sounded radiant and his phrasing was Lieder-like in its musicality. I had make a beeline to hear him sing Florestan again, as well as other roles.

Ulrike Kunze’s unit set offered up the second Orwellian production of the week in Prague, following on from the F. X. Šalda Theater’s Rachmaninoff double bill (review click here), though this one looked as if situated in more recent times than the 1930s. The costumes, also designed by Kunze, were likewise modern dress and well attuned to the production’s general theme of social realism with a paradoxically imprecise idea of time and place.

All in all, this Fidelio left a similar impression to other stagings by Vera Nemirova. It often feels like she could do more, or make more interesting choices in her framing, but her work is always focused and what you get is never bad in itself. And as with every other Nemirova production, you wonder about her reputation as an enfant terrible. Over a decade ago, she staged Macbeth at the Wiener Staatsoper (in which Erika Sunnegårdh also appeared, as Lady Macbeth) and bourgeois Vienna was scandalized by some mild nudity and a few pints of stage blood. The outrage was so great that the production was pulled after six performances and never shown again. People and critics who had showed up for an opera in which a sleeping monarch is stabbed to death wouldn’t shut up for years about the upstart Bulgarian woman who showed a sleeping monarch being stabbed to death. How tasteless!

A scandal manufactured by self-indulgent, entitled elements of the opera-going public, however, provides little to no insight into a track record. Given that Nemirova (scolded into line?) generally creates rather safe productions and a couple of years ago suppressed her creative self-expression almost entirely to reconstruct a Karajan production of Die Walküre at the Salzburg Easter Festival, maybe it’s time to change the record when discussing her work?

Sebastian Smallshaw