Austria Dvořák, Rusalka: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Vienna State Opera / Tomáš Hanus (conductor). 4.2.2020 performance at the Vienna State Opera (directed by Jasmina Eleta), streamed on 15.1.2021. (JPr)

Austria Dvořák, Rusalka: Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Vienna State Opera / Tomáš Hanus (conductor). 4.2.2020 performance at the Vienna State Opera (directed by Jasmina Eleta), streamed on 15.1.2021. (JPr)

Production:

Director – Sven-Eric Bechtolf

Sets – Rolf Glittenberg

Costumes – Marianne Glittenberg

Lighting – Jürgen Hoffmann

Choreography – Lukas Gaudernak

Chorus master – Martin Schebesta

Cast:

Rusalka – Olga Bezsmertna

Vodník (Der Wassermann) – Jongmin Park

Ježibaba – Monika Bohinec

Prince – Piotr Beczała

The Foreign Princess – Elena Zhidkova

The Hunter – Rafael Fingerlos

First Nymph – Diana Nurmukhametova

Second Nymph – Szilvia Vörös

Third Nymph – Margaret Plummer

Gamekeeper – Gabriel Bermúdez

Kitchen boy – Rachel Frenkel

Rusalka is Dvořák’s most admired and frequently performed opera, especially of course, in his Czech homeland where it has been performed almost continually since it was premièred in 1901; though it is seen rather less often elsewhere. Jarosalav Kvapil finished his libretto – based on the fairy tales of Karol Jaromír Erben and Božena Němcová – in 1899 before he had any contact with Dvořák. The plot involves a Rusalka – a water nymph from Slavic mythology that usually lives in a lake or river – who longs so much to become human that she is willing to give up her voice and so be able to marry the handsome Prince with whom she has fallen in love while he hunts near her lake. The story contains certain elements in common with Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid and Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué’s Undine. Kvapil began looking for a composer interested in setting his text to music and he was alerted to the fact that Dvořák was looking for a project. The composer knew Erben’s stories well and began his first draft in April 1900 before finishing the opera by the end of November. Dvořák had previously composed four symphonic poems in the late 1890s inspired by some folk-ballads by Erben, so Rusalka has been considered by opera critic Max Loppert as the culmination of his exploration of a ‘wide variety of drama-creating musical techniques’.

I remember taking issue in 2012 with an essay by David Beveridge – as background for a Covent Garden performance – which asserted that despite Dvořák taking inspiration from Wagner ‘…nevertheless, there is scarcely a passage in Rusalka that one could imagine as actually having been composed by Wagner’. Utter nonsense! A few years later, the conductor Sir Mark Elder – who has long championed Rusalka – was interviewed during a broadcast performance from the Met and explained that his raison d’être to keep returning to this opera was out of curiosity ‘to find even the smallest influence of the beast of Bayreuth’ and explore how Wagner gave Dvořák the ‘technique and equipment to explore the darkness’ in the tale! For good or ill I often indulge in ‘Wagner spotting’ in my reviews and Rusalka provides me with so many opportunities beginning with some Wagnerian colours infused into the overture.

The major confrontations are Wagner pure and simple: in Act I Rusalka’s father, the Water Goblin (Der Wassermann) confronts three ‘catch us if you can’ Wood Nymphs just like Alberich and the Rhinemaidens in Das Rheingold; in Act II Rusalka begs her father’s forgiveness just like Brünnhilde pleads with Wotan in the final act of Die Walküre; and in Act III Rusalka’s kiss – which promises death and damnation for the Prince – prompts a closing duet reminiscent of that for Siegfried and Brünnhilde (in Siegfried). In all these cases the music pays homage to the original Wagner! If the Water Goblin is Alberich, then – if you know your Wagner – the witch Ježibaba is a combination of Erda and Klingsor, whilst the Foreign Princess is obviously Ortrud. There is much more amongst all these ‘borrowings’ including the ‘Entry of the Gods into Valhalla’ from Das Rheingold that is heard a number of times. Let us also not forget that Ježibaba will be familiar if you have seen Humperdinck’s Hänsel und Gretel and it should be remembered he was an acolyte of ‘the beast of Bayreuth’.

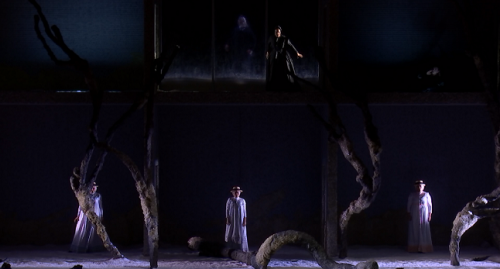

Sven-Eric Bechtolf’s production was new in 2014 and was revived here by Karin Voykowitsch. How much psychoanalysis Bechtolf brings to it I will leave to others, but he explores Rusalka’s repressed sexual fears and desires, as well as her ‘mommy’ and ‘daddy issues’. Rolf Glittenberg provides impressionistic sets and for Act I there are two levels seen at the back with the upper one representing the world of the woodland creatures – or possibly the ‘real’ world – with its tank-like central section. The snow-covered foreground below has a number of gnarled ice-encrusted tree trunks where we see – for the most part – Rusalka’s nightmarish imaginings. It is important not to miss the significance of the opening scene revealing a stern household and ‘mother’ Ježibaba slapping (wayward daughter?) Rusalka as her three ‘sisters’ in nightdresses and boaters on their heads morph into cavorting Wood Nymphs wearing Marianne Glittenberg’s slinky body-hugging white and blue creations.

Rusalka appears and is unable to move her legs properly and drags herself around encumbered by a long purple ‘veil’ and she asks Ježibaba for ‘a human body and a human soul’ so she can be united with the Prince. The witch wears a feathered black gown, and the ground is littered with dead ravens by the look of them. (Clearly, Bechtolf understands Wotan is also referred to as the lord of the ravens.) Rusalka is fed a heart of one of these black birds (whatever they are) and now in white (having lost her ‘veil’) she rises precariously to her feet – mute but human – as we hear the hunting horns of her Prince’s approach (opening of Act II Tristan?). He arrives with his gun and wearing traditional Austrian hunting clothes. The conflicted Rusalka’s ‘mother’ and ‘father’ seem to be watching from above as her ‘sisters’ call for her whilst the somewhat bemused Prince sings ‘Come with me, my fairy spirit!’.

Act II should be ‘the garden of the Prince’s castle’ but we prominently see a large bed with a garland of white flowers in front of panels of frosted glass behind which we initially see, Ježibaba, Water Goblin, Wood Nymphs, Prince, and Foreign Princess. On the bed the Gamekeeper (hyperactive, bare-chested and in pale yellow lederhosen) and his nephew the Kitchen Boy gossip about Rusalka and the Prince. Dvořák’s polonaise brings us two ballet dancers revealing Rusalka’s fear about her wedding night as a rather portly de-trousered gentleman is shown manhandling and attempting to ravish his young bride. We had been introduced to the Prince again – now dressed for his wedding in frock coat and grey trousers – who is being stalked by a seductive Foreign Princess, looking facially rather like Angelina Jolie’s Maleficent, but dressed in an all-dark red ensemble with more feathers concealing a glittering gown. The Foreign Princess curses Rusalka and the Prince, just as Ortrud invokes the old gods to wreak vengeance on Elsa and her swan knight in Lohengrin Act II. There is a tableau showing the wedding party gathering whilst the Water Goblin reappears and Rusalka asks for his help because the Prince no longer loves her. Once more we see a wedding veil (and the entire dress this time!) ripped up and Rusalka schizophrenically exclaims ‘I am neither woman nor wood nymph’. The Prince is equally ‘torn’ in his feelings for the Foreign Princess and Rusalka: in the end the Water Goblin curses him after he is rejected by them both.

Act III begins with Rusalka’s ‘family’ dining above and Rusalka below bemoaning how her ‘happy youth has come to an end’ and how she doesn’t know whether to return to them or stay in the human world. As Ježibaba enters to sit down and knit(!), Rusalka collects knives from across the stage as she is told ‘only the frenzy of human blood can set you free’ before she is banished back to the water. The Gamekeeper and Kitchen Boy arrive seeking Ježibaba’s help to save their Prince. In Bechtolf’s staging they will not ‘live happily ever after’ as (spoiler alert!) the Kitchen Boy is killed and gets devoured by Ježibaba and the Wood Nymphs, and there is a suggestion the Gamekeeper also meets the same fate. The stage clears as the Prince enters to sit against a tree remembering his first encounter with Rusalka. She was darkhaired then but now it is silvery white like her sisters and – similar to Wagner’s Dutchman – Rusalka proclaims she is ‘neither living nor dead’. In fact, Rusalka is a bludička, a spirit of death, doomed to emerge only at night to lure humans to their death (like the Wilis in Giselle). As the Prince sings ‘Let me die in your kiss! […] Your kisses will redeem my guilt!’ he is enveloped in a black shroud against the tree whilst the Water Goblin laments and Rusalka prays ‘May the eternal God have mercy on his soul!’ before lying at his feet.

Despite a principal cast of many nations who were all experienced in their roles – Rusalka (Ukrainian), Prince (Polish), Ježibaba (Slovenian), Foreign Princess (Russian) and Jongmin Park (South Korean) – the Czech language of Rusalka held no fears for them as far as I could discern. On hand anyway was Czech conductor Tomáš Hanus who has conducted several performances of this opera and has this music in his heart. The Orchestra of Vienna State Opera (of course, the Vienna Philharmonic) sounded wonderful as ever during the broadcast. Hanus brought Dvořák’s rich orchestration to vibrant life and his Rusalka had idiomatic ebb and flow with no longueurs. There were many virtuosic solo moments but harpist Anneleen Lenaerts deserves special recognition for her contribution.

Although the singing was uniformly excellent, it was the ease and naturalness of the acting that was equally impressive. Olga Bezsmertna – who stepped in to the first performances in 2014 at short notice – was an outstanding Rusalka with a full, firm, slightly steely, soprano voice that was even across the range. Bezsmertna could sound exquisitely tender at one moment and declamatory the next and her ‘Song to the Moon’ was (an oft-used word) ravishing with pliant phrasing and beautiful breath control. Piotr Beczala is a most impressive singer whatever he is in, and his portrayal of the Prince was a typically honest and earnest one. His tenor voice was dark and rich – almost ‘chocolatey’ – and Beczala had no difficulty with the higher lying phrases. The Prince in this opera goes through an intense range of emotions and Beczala made each one seem real to him and to those watching.

Monika Bohinec chewed the scenery as Ježibaba, and she had a fearsome presence and booming chest tones though still with plenty of colour at the top of her voice. Jongmin Park brought to his pasty-faced Water Goblin some unexpected intimations of a father’s love for his daughter, as well as conveying convincingly his sorrow at Rusalka’s plight. Park is a remarkably sepulchral – though smooth – bass though he was another to traverse with vocal ease both his character’s lyrical phrases and climactic outbursts. Elena Zhidkova is an incomparable singing-actor and perfectly captured the Foreign Princess’s imperiousness and demanding nature. Zhidkova sang reasonably well though her mezzo lacked body and she could sound a little shrill and over-parted at her most intense. The chorus are not involved very much but sang eloquently and all the smaller roles of Wood Nymphs and retainers were well taken. I am loath to single out any one of them, though Diana Nurmukhametova – who was an appealing First Nymph – might be someone to look out for whenever opera starts again in the future.

It was troubling to hear a February 2020 Vienna audience doing so much coughing when there was no music and it made me wonder whether the dreaded COVID-19 was already rife in the city then?

Jim Pritchard

For more about what is available from Vienna State Opera click here.