Switzerland Lehár, Das Land des Lächelns: Soloists and Chorus of the Opernhaus Zürich / Fabio Luisi (conductor), Opernhaus, Zurich, 16.6.2018. (CCr)

Switzerland Lehár, Das Land des Lächelns: Soloists and Chorus of the Opernhaus Zürich / Fabio Luisi (conductor), Opernhaus, Zurich, 16.6.2018. (CCr)

Cast:

Prinz Sou-Chong – Piotr Beczała

Lisa – Julia Kleiter

Mi – Rebeca Olvera

Graf Gustav von Pottenstein – Spencer Lang

Tschang – Cheyne Davidson

Obereunuch – Martin Zysset

Production:

Director – Andreas Homoki

Choreography – Arturo Gama

Set designer – Wolfgang Gussmann

Costume designers – Wolfgang Gussmann, Susana Mendoza

Lighting designer – Franck Evin

Every concertgoer has their own irrational little litmus tests as to what they will go see no matter what, and what’s not worth leaving the house for. There are strong arguments for discarding these from time to time and just seeing something outside your favoured realms, but we all fall back into our old habits. The young man seated to my left at Land des Lächelns, the 1929 romantic operetta, for example, had come with no knowledge of the plot nor of German, but was an ardent devotee of lyric tenor Piotr Beczała. The elderly ladies on my right sang along to the various Tauberlieder of the piece, ‘Dein ist mein ganzes Herz’ chief among them. I myself hadn’t planned on attending, but my curiosity as to how Fabio Luisi would conduct operetta got the better of me. Outside the opera house, several thousand viewers had assembled in casual dress and with wine in tow, ‘opera for all’. Whatever it is that hooks one in, it is often those performances in which one expects the desultory where true delight emerges.

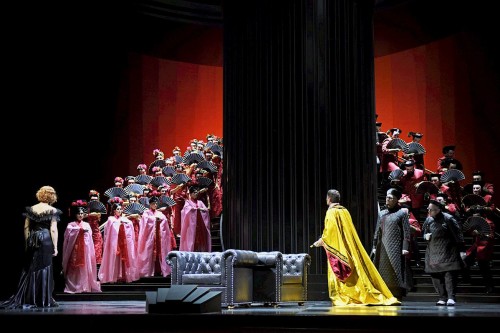

The story in brief (very brief, in fact, as Andreas Homoki has stripped this Land des Lächelns of several characters and much dialogue, intensifying the music): Lisa, a worldly Viennese woman, meets Prince Sou-Chong, a Chinese diplomat. They love each other despite the yawning cultural chasms between them. When Sou-Chong is named Prime Minister of China (because why not), Lisa is happy to accompany him. Once there, she is soon lonely and isolated from her busy new husband and the coldness of the Chinese court. When Sou-Chong’s handlers insist he marry Chinese brides and treat Lisa as a mistress or worse, he consents; she in turn gets rescued by her admirer the Count, who has conveniently arrived from Vienna, but not before that Count himself has taken a fancy to Sou-Chong’s sister Mi, and sung to her about the universality of love. They all live sentimentally ever after.

This delightful production, a revival for Zurich’s annual open-air opera broadcast in the square before the opera house, makes a series of small decisions to convey this piece meaningfully 90 years on. For one thing, Luisi’s conducting yielded a big, marvellously-velvety but still-clear sound. The conductor’s programme notes said that he finds operetta trickier than other genres to conduct, and that he has to tread carefully around too much, but this was no Goldilocks reading. The ‘Chinese’ pentatonic colours of the score were fully embraced, Julie Palloc’s harp was in glorious unison with the strings, and at the end of the first half, when the ensemble staging is just so-so and the chorus’s singing lacklustre, Luisi made his finest argument in favour of Lehár as a composer by ramping up the volume and pushing the moment forward. Indeed, there’s an instance in the second half, when the winds that represent Sou-Chong’s authority over Lisa and the strings that sound of Lisa’s consternation combine for an effect that is Stravinsky-meets-Offenbach. That alone is worth leaving the house for.

Beczała returns as Sou-Chong, and has the finest feeling for this music. He scoops his vocal ascents just so, sweeps through big phrases, keeps the syrupy text articulate, and moves into the higher registers of his songs with ringing grace. This is music for which the word schmaltzy was invented, but Sou-Chong is a compelling character, and Beczała’s reading is one of deep pathos amidst restrained poise. I found Julia Kleiter less satisfying as the heroine Lisa; she refrained from embracing the Viennese dialect, the flapper naughtiness, the cabaret-style, text-heavy storytelling that the role kept trying to afford her. Kleiter’s top voice is gorgeous, her sound often light and gay, but her quavering vowels and vocal colourings didn’t help her sell the role.

More convincing was Rebeca Olvera, who dove head-first into the camp of her role as Sou-Chong’s sister Mi while still upholding its dignity and then sadness. She achieved this by the production’s intelligent staging and a fabulous stage presence as she flirts with the Austrian Count. She made the role her own, vocally rich, with a deep vibrato, but every bit the part. Spencer Lang’s Count von Pottenstein took a similar approach, with vaudeville-light acting in the foreground but elegant singing to match.

A word on the evening’s broadcast to the square outside: there was some debate in the Zurich media whether the ‘Oper für alle’ broadcast is truly for all, and there is indeed something strange about having full-price tickets inside the opera house while the hoi polloi is thrown a simulcast to which to picnic. The waters of this debate run deep; in 1980 there was street violence over the city’s subsidies for this house over other, more populist priorities. I am torn between the inordinate expense of opera this excellent and the need for state funding for more accessible art. The Opernhaus does offer several discounts for its tickets, and this annual event is a well-meaning effort to make opera and ballet more prominent to a wider public, but there is always more the house and the city can do.

In any case, the weather was splendid, the production charming, the singing and conducting first-rate, and the public outside looked as delighted by the performance as anyone else. This night was a success by any definition, and here’s hoping more than a few people’s little litmus tests were rethought.

Casey Creel