United States Brooklyn Art Song Society – Iconoclasts III. Ned Rorem: Sarah Brailey (soprano), Annie Rosen (mezzo-soprano), Steven Eddy (baritone), Dashon Burton (bass-baritone), Michael Brofman (piano), Daniel Schlosberg, (piano), Danny Zelibor (piano), Brooklyn Historical Society, Brooklyn, 4.1.2019. (RP)

United States Brooklyn Art Song Society – Iconoclasts III. Ned Rorem: Sarah Brailey (soprano), Annie Rosen (mezzo-soprano), Steven Eddy (baritone), Dashon Burton (bass-baritone), Michael Brofman (piano), Daniel Schlosberg, (piano), Danny Zelibor (piano), Brooklyn Historical Society, Brooklyn, 4.1.2019. (RP)

Rorem – ‘My Papa’s Waltz’, ‘Root Cellar’, ‘Clouds’, ‘The Waking’, ‘Little Elegy’, ‘I Strolled Across an Open Field’, ‘Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair’, ‘Early in the Morning’, ‘Visit to St. Elizabeth’, War Scenes, Poems of Love and the Rain

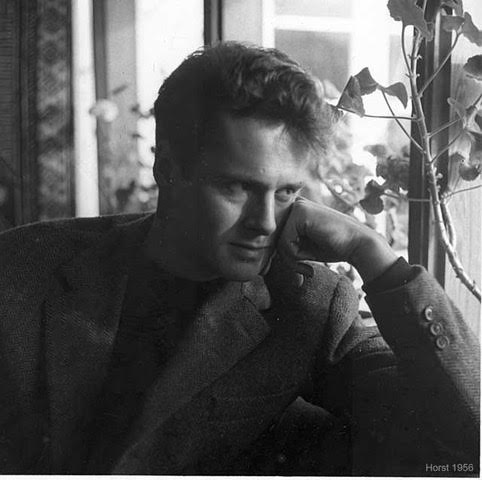

Ned Rorem, now 95, was long ago anointed ‘the world’s best composer of art songs’, albeit by an American magazine. Few would dispute that he is a master of this intimate genre, but he composed symphonies, chamber music and operas as well. It was hard once to avoid his name on a song recital program, but these days it is less frequently encountered. What a joy then to discover that the Brooklyn Art Song Society was presenting an evening of some of his best ones.

When I discovered the world of song, I chanced upon Rorem. Together with my great friend Betsy Walker, a contralto as well as a music librarian (she knew all the good books), I read his scandalous diaries lolling on the beach. I met mezzo-soprano Mildred Miller in Pittsburgh and discovered the frenzy of ‘Bedlam’ from her recording of what the composer termed his most dramatic song. Before having eaten a croissant or sipped a café au lait (although I had seen Paris), I had inhaled ‘Early in the Morning’. ‘The Lordly Hudson’ meant NYC; ‘Home, Home’ still sounds in my soul every time I catch sight of the majestic river upon returning to the US.

For War Scenes, Rorem excerpted texts from Walt Whitman’s Specimen Days, a poetic memoir of his time as a Civil War nurse. This cycle of five songs resonated differently from his other works then, and it still does today. It bears the dedication, ‘To those who died in Vietnam, both sides, during the composition: 20-30 June 1969’. Raised a Quaker, Rorem was a pacifist. His music for War Scenes is not angry and defiant but, rather, austere and bold and as luminous as Whitman’s words.

Rorem cobbled together the texts for the cycle with his customary discerning literary taste and an exceptional sensitivity to the inherent but understated power of Whitman’s imagery. The first and last songs are reflections on the nature of war, while the inner three relate scenes as disparate as a rebel solider with his brain seeping out of his shattered skull and the frivolity of an inaugural ball amidst the carnage. Their message is timeless, as evidenced by a tweet – ‘5 eyes. 5 arms. 4 legs. All American’ – posted with the photograph of three battle-scarred US Congressmen on the floor of the US House of Representatives a day before this concert.

Michael Brofman dug into the angular and explosive outbursts of Rorem’s accompaniments while displaying passion and sensitivity in moments of introspection, as when Whitman recalled sitting silently by the bedside of a dying young solider. The phenomenally talented Dashon Burton with his supple bass-baritone gave voice to the despair and anguish as well as Whitman’s inherent grandeur. Calls to battle rang out forcefully, while his hushed parlando could comfort as well as instill horror.

The other song cycle was Poems of Love and the Rain, composed in the early 1960s. Given Rorem’s literary bent and penchant for self-explanation, there is no need to guess about what he set out to achieve technically or emotionally. He chose several poems that deal with unrequited love against a backdrop of ceaseless rain – establishing a mood rather than relating a story. The poems are repeated in reverse order, in settings as contrasting as Rorem could manage, until returning to the same text with music that is basically identical to the first version although a halftone lower. He called the order ‘pyramidal’.

Rorem composed the songs for Regina Sarfaty, whose voice he described as ‘rich and blue, dramatic and anguished’. Mezzo-soprano Annie Rosen was all that and more, especially in terms of sheer beauty of sound. In W. H. Auden’s ‘Stop All the Clocks’, she was alternatively urgent and intense, histrionically bemoaning the love that had just walked out the door. Rosen instilled Theodore Roethke’s words, ‘My pillow won’t tell me where he has gone’, with a heartbreaking simplicity, while a state of ecstasy prevailed in e. e. cummings’ ‘in the rain’, which rejoices in a lover’s ‘dancesong soul’.

Daniel Schlosberg was the superb pianist, capturing the fleeting emotions of the songs as deftly as Rosen and performing the dramatic Interlude at the apex of the cycle with virtuosic aplomb.

The recital had begun with soprano Sarah Brailey and baritone Steven Eddy, accompanied by Danny Zelibor, performing nine Rorem songs. Eddy gave voice to the bliss of being twenty and a lover in Paris in ‘Early in the Morning’ with his firm, fine baritone. ‘Visit to St. Elizabeth’s’ (a psychiatric hospital in Washington DC and the Bedlam in Elizabeth Bishop’s poem) was no less frenetic for his seamless phrasing and the sense of line that he brought to it. He also got to sing Rorem’s wonderful setting of ‘Root Cellar’ in which voice and piano vividly depict the dank and smells of a subterranean hotbed of life.

To Brailey fell the treat of singing songs in which Rorem was alternately wistful, as in the simple, lovely setting of Elinor Wiley’s ‘Little Elegy’; ebullient, as in Roethke’s ‘I Strolled Across an Open Field’; and uncharacteristically nostalgic in his arrangement of Stephen Foster’s parlor song, ‘Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair’. With her gleaming, bright soprano, she seemed to effortlessly capture the subtle nuances of these little gems.

Zelibor was as stylish and accomplished a pianist as his two colleagues, the alternating chords of ‘Clouds’ transporting all heavenward in music as atmospheric as any Rorem ever composed.

Rick Perdian