A Bruckner Odyssey: The Ninth Symphony Sir Simon Rattle talks about the four movement version

(Also available in SACD format)

Live-recording, 7th-9th February 2012,

Philharmonie, Berlin

(Click also here: Anton Bruckner: Symphony No 9 in D minor WAB 109 – The unfinished Finale)

© Aart van der Wal, June 2012

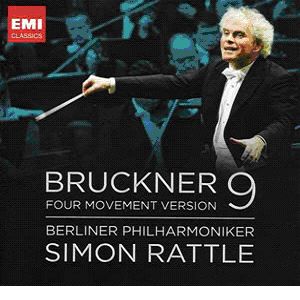

Last month EMI Classics released their CD with Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony in the four movement version, a live recording by the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Sir Simon Rattle. Early June, Simon Rattle was here, in Rotterdam, on a European tour with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and French pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard. He conducted a programme with music by exclusively French impressionists (Fauré, Ravel and Debussy). Very early in the morning, on the day after the concert I met him in his hotel to talk about his Bruckner recording.

Obsession “The first thing I noticed when studying this Bruckner Ninth finale were those strange transition passages you can find in any typical Bruckner finale. But here, in the Ninth, I strongly felt as if Bruckner was obsessed with the last things in life, or maybe even the very last thing he could possibly hold onto this. As if he was thinking that when he could hold onto this, work on this, he could find his way out of this obsession. There is absolutely no doubt in my mind that Bruckner was going through an existential crisis within himself. However, there is also no doubt that he was dealing with a compositional crisis, as many composers do, also composers who are writing finales for their symphonies. Look at Brahms, how much he struggled with writing the finale for his First Symphony, as the different versions that exist tell us.”

Extraordinary vista “All these great transition passages in Bruckner’s symphonies lead to some extraordinary vista, some wonderful moment which leads you out of this world. When hearing this finale for the very first time it almost instantly became clear to me, even without a score, that the music that is there, which is a lot, was far more interesting than I had thought or people had said; but also that it was a really tough nut to crack. I could not yet put the various pieces firmly together, but I could grasp that each and every one of them was absolutely magnificent. Over the years, I had heard a couple of other completions, but they were badly put together and even dreadfully played, doing no service, no justice to Bruckner’s masterpiece at all.”

A continuous manuscript: Mahler’s Tenth “Doing justice to the composer is something which Deryck Cooke did when he worked on the performing version of Mahler’s Tenth, which is as good as anything that Mahler wrote. In the sense that Mahler lacked the opportunity to perfect it. But all is there for you to play. The first time I heard that there was something like a Mahler Tenth, I was eleven years old, and living in Liverpool. I was twenty-four when I made my first recording of the work with the Bournemouth Symphony. Sure, I did not grow up with the romantic idea that there was only that Adagio and this little Purgatorio, but at that time a performing version of the Tenth was still haphazard. Imagine, still today only the Adagio is often played, although happily there is a generation who will want to listen to the whole work, and take it on its merits.”

“I’m aware that most ‘typical’ Bruckner conductors did not and still do not want to touch the Finale of the Ninth, for whatever good or bad reason, but I think I have one advantage, which is that I have spent so much time in my life dealing with Mahler’s Tenth. I didn’t only know Deryck Cooke, but all the people who got involved in this ‘reconstruction’ work later on. All strongly driven characters like Colin Matthews and Berthold Goldschmidt, who became very much a part of our family. This is also how I met Kurt Sanderling, who – like Goldschmidt – was thrown out of the Vienna opera house by Karl Böhm. I could closely watch the whole progression of the Mahler Tenth; and, of course, I heard everybody’s prejudice. Even from those who had not even seen the score or heard the piece. Basically, it was simply the inability of those opposing to accept that what was there might be different from their own pre-conception. Whereas we knew every bar which had been written down by Mahler. We understood what it really was: a continuous manuscript, not less and not more. Of course, Mahler would have refined it in countless ways, if he had lived long enough. What is there is not perfect, but it has such a truth that it trumps all other considerations.”

Catch up “Years ago I was talking to Nikolaus Harnoncourt about Bruckner’s Ninth Finale. Whenever I meet him he is always incredibly excited about the next thing he is doing. I don’t have to tell you how persuasive he usually is! One of the first things he said to me was that we had a great performing history of the first three movements, a history we all take part in, but none of the last movement. That we had to catch up with this Finale, this tabula rasa, knowing so well the gravity and density of those first three movements. This was also something the orchestra very well understood when we discussed the work: we all have to catch up with this and find the one and only way to play the Finale in the same, convincing way as the other movements. At that time, Nikolaus was more in line with the idea that his performance of the Finale should only entail Bruckner’s and no one else’s notes. That is typically Nikolaus and that is why we all love him. But I agree with you as far as his ‘workshop’ model* for the Finale is concerned: with so many blank spaces the structure gets lost. However, what he did was opening the debate and give people a chance to hear what is really there. Also remember what he said to each and everyone: go and look in your attics, because a lot of these missing pages must be somewhere. Actually, since then, there have been one or two more discoveries; and I am sure there still will be. There might even be a Stieg Larsson out there writing a big mystery novel about where the rest of the symphony is!”

Vintage Bruckner “Nikolaus encouraged me to look at the sketches again. Long after that there was that great performance at the Salzburg Festival in 2002, where he conducted the Vienna Philharmonic*. Later, in November 2007, Daniel Harding conducted the four movement version in Stockholm, with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. I got the complete score of it, the so-called S(amale) M(azucca) P(hillips) C(ohrs) edition, prepared by those four Bruckner scholars: Nicola Samale, Giuseppe Mazzuca, John Phillips and Ben Cohrs. I got in touch with Ben in Bremen.”

“It took a while really to study the work. It is one of those pieces which keep their mysteries, irrespective of how much time you spend with them. How many years did it take me to get anywhere near Beethoven’s Grosse Fuge, or Bruckner’s Fifth! And now that Ninth Finale, which I had to unravel. To me it was a new Bruckner symphony I had my hands on. It took some months before I could tell the Berlin Philharmonic about it, with enormous respect for what these four scholars had put together. When I had worked it all through I was convinced that this is what we should do, what was really important: to go for it, to play the four movement version of Bruckner’s Ninth. Period.”

“With this Finale you can still tell that in some ways it is a sketch, but there is so much of vintage Bruckner in it. What this team has accomplished is to create a frame that makes it playable and understandable. Of course, this cannot be exactly what Bruckner finally would have offered to the world, but we now have the possibility of performing and hearing the symphony as a really complete work. Which also means rehearing those extraordinary previous three movements through the prism of that Finale. It has definitely changed my perception if not the conception of the whole work, as I look at it now from a very different perspective. I so much hope that the full version will be frequently performed, but I equally hope that if not, conductors and orchestras will closely study the Finale, to imagine what it is, because it places such a weight on the preceding movements. The Adagio is not a “Leb’ wohl”, as in ‘Das Lied von der Erde’. It is not! It is as extraordinary as the Adagio of the Eight Symphony: it is a part of a journey.”

“Even in a work by a genius you notice conventions, in the sense of familiar lines, harmonic colouring, specific transitions, rhythmic progression, dynamic sequences, and an unambiguous way of orchestral thinking. Also – and it may be a paradox – even if they are not, like in this Ninth Finale.”

“The great master stroke of this finale version is the great chorale, which Bruckner always uses. And there is only one chorale in there, as there is in the Adagio. One stroke of conductive genius, I would say. But the attempt to use the finale chorale as an ending would not have worked: no matter how magnificent it is: it is not that.”

Catastrophe “As a conductor, working yourself through this incredible Finale, you will have a very simple problem to deal with, which is that all the themes together from the previous movements have to be exposed in their related tempo. You absolutely cannot expand the themes of the first and the slow movement because then they would have nothing in proportion to the Scherzo or the Finale. You have to find a more disciplined way of playing these, as you do in the Eight. That was a very huge and important insight for me: that basically the whole Ninth has to ‘walk’ in a related tempo. Doing so is also beneficial to the structure of the whole piece. At the same time you have to imagine the huge struggle in this Finale, not like that of the Sixth, which is an ending, instead of a great Finale: much of the work is already done at earlier stages in that symphony. No matter how strange and extraordinary it is, it is and remains a problem finale which just counterbalances the weight of the first movement. In the Ninth it works out quite differently. Here I see Bruckner in crisis, and I see him in crisis in the Finale, when he writes it. And it may be that at the end of it all the reason that he was not able to finalise it was that he had set himself such a problem in doing it. What he left to us is an incomplete, problematic, astounding work of a genius at the height of his powers. This is a work that I desperately wanted to explore, although it is not a comfortable experience in any sense, more like seeing the black paintings of Goya, but a very important experience nevertheless.”

“What you said a few moments ago is so true: this is unmistakably Bruckner, but a different one. It is as if you meet a friend after years who has gone through a crisis. Years ago, I met a friend in Los Angeles who had a lobotomy. It was recognisably the same person, but you had to search. The Finale reminded me of that, although the lobotomy evoked the opposite: it had calmed down this person, whereas with Bruckner it is quite the opposite. His calm had gone and replaced by obsession. This was the man who tried to count the number of leaves on the tree. You hear this in the music, it tells you about a person and his religious beliefs in crisis. Listening to this most telling Adagio makes you aware that a catastrophe is going on. This music tells you about losing faith, that moment just before this gigantic dissonance tells us everything.”

“I see now clearly to where these three first movements are pointing, and that the Adagio is no kind of resolution. It is a marker in that incredible struggle, we are still underway. That SMPC Finale shows us now what it would have been like, we have the chance of experiencing it as much and as often as we can. That is a gift. It is important that orchestras like the Berlin Philharmonic take this with them. Bill Clinton once called it the ‘bully pulpit’ of the American presidency: we, as an orchestra, must do things like this just to remind people that the Finale is there. Whatever else gives it also another degree of so much credibility? That people will feel: ah, maybe that if they do that Bruckner Finale it is worth looking at it. That is all I would ask.”

SecondVienneseSchool “This entire work goes far beyond tradition. It makes you realise again and again that Mahler and Berg would have been unthinkable without it. Bruckner moved harmony forward to a stage Wagner did not dream of. Bruckner was exceedingly important to Berg. You see so much of the same harmonic world, how much they share in their music. There are certain harmonic imprints in Berg’s music which are so similar to Bruckner’s. Webern was also connected to Bruckner: he was a wonderful Bruckner conductor, to say the least. Quite different from Schoenberg, who was more attracted to Brahms. Look for instance at his orchestration of Brahms’s Piano Quartet in G minor. Webern was also painstakingly accurate, not only in his compositions but also in his conducting. He pressed really hard to achieve the kind of perfection which was virtually unknown at that time, or even impossible. That did not always work out fine. I remember Wyn Morris, who was to perform a concert with the Royal Liverpool Orchestra. At the rehearsal he found himself in a vacuum: all musicians had left their seat and walked away, leaving him alone, on the rostrum. A conductor without an orchestra.”

“One of my piano teachers in Liverpool turned the pages for Webern when he played the Piano Variations and he remembered how extraordinary that was, Webern playing vibrato on each and every note! Is that possible on a piano? No, but it worked that way, psychologically. Webern’s desperation for everything to quiver in life, a kind of thrilling.”

“Bruckner and the Second Viennese School is one fascinating story. Both have become much closer to us. The music of Berg, Webern and Schoenberg is at our doorstep, it is clearer than ever. People even hear it now as romantic music. Orchestras can now play it. Many years ago, in London, I was privileged to attend rehearsals by Pierre Boulez. It was a great learning process for all of us. How he taught our orchestras to play these pieces, and to play them with intensity and beauty, as if it was romantic music. As Bernstein was the catalyst for Mahler in Vienna, Boulez was the catalyst for the composers of the Second Viennese School. He showed that their music could be played perfectly in tune, with great flexibility, like chamber music. Boulez was a revelation for all of us.”

Schubert “Yes, there are clear traces of Schubert in Bruckner’s music. When I first played as a cymbal player in the Bruckner Seventh with the great conductor Rudolf Schwarz (he headed the Jewish orchestra in Vienna, during the Second World War), I discovered Schubert’s G major Quartet, in which there are so many points that lead directly to Bruckner. At the same time, it is very important for conductors and orchestras to understand that there is so much Schubert in Bruckner. We should not make the mistake to play Bruckner much differently from Schubert. It has to be as ‘classical’ as Schubert, and very disciplined because this is very expanded music after all, as Schubert’s late quartets are very expanded. I never forget what Günter Wand once said to my orchestra: ‘Bruckner’s harmonies are romantic but the rhythms and the structure are classical’. I found this so important that I kept saying it, over and over again. He was absolutely right, because you cannot lose this frame, be indulgent with it. You really must be strict about the rhythms, the structure and the relations. The harmony may lead you to Wagnerian flexibility, but that is a grave mistake. Bruckner’s great admiration for Wagner does not mean that his music ‘walks’ in the same way. This is something we all have to learn, we all need to work out. This was one of Wand’s important lessons. I went to a lot of his rehearsals. He was always kind and generous to me, and he learned me so much about discipline in playing Bruckner.”

Heritage “Was the Finale a difficult piece to perform? I would say astonishingly difficult, as the whole symphony is. But we, i.e. the orchestra and I, are used to this kind of complexity. But there is another angularity of how Bruckner writes. It is like the string problems in Schoenberg’s works: a kind of edginess, discomfort. Berg and Webern cared enormously that their music was playable, however hard it is. Schoenberg never did. It reminds me of the difficulties in playing Bruckner, particularly for the string players. They desperately need either the extra hands you have as an organist using the pedal, or the sustaining pedal on the piano. As ever, as with Mahler’s Tenth, it was important for me also to remind the orchestra that everything that was strange or even impossible to play, was written by Bruckner. The music which we had no problem with was the music that had been put together by the team! Everything that is outlandish and strange is directly from Bruckner. But of course, that first moment with the Finale was very strange. The Berlin Philharmonic is an orchestra which questions everything anyway, and then there is this new part. So I wanted to brief the orchestra about it, asking all of them to come, because I didn’t want to do this speech twice; particularly not in my terrible German. I had written out important phrases to make it grammatically understandable what I had to say. It was interesting, at the point where I was able to explain the whole concept: this is what it is, this is what is there, this is the story of the Finale and this is the history of its conception, because basically none of them knew that the Ninth was played in a highly censored version until in the thirties, harmonised and re-orchestrated, looking very much like the decorated and prettified orchestration of Twilight of the Gods. And I begged them, saying that we so often judge on a first hearing, to play it a few times, and judge after they had played their third concert, because it had taken me months to come to terms with this. In the sense of please, give this a chance, as we do with any other piece which takes time to reveal its secrets. And then, typical Berlin Philharmonic: everybody wanted to do his own research. After the first day working on the piece, rehearsing with the string section only, simply to work on it slowly, they came back to me, telling they had been in the library and on Google to find out more. A number of players even told me that maybe there was no way back from this: that from now on we should consider the Ninth to be a four movement work. Although another performance of the Ninth will be the three movements only, in Baden-Baden, because the program was already there. But after that? We will play the ‘full’ symphony because it is from now on an inseparable part of our musical heritage, of our history. Yes, I am sure that other conductors will still keep the traditional three movement version alive, but it just might happen that our contribution will finally change that. That a new generation stands up to try it and at the end make it part of the standard repertoire, as has happened with that remarkable Mahler Tenth. As if you are given a glimpse into Bruckner’s workshop, and this is incredibly valuable. And it can tell you a lot about the other Bruckner symphonies.”

“I did not yet hear from other conductors after our performances, or even this recording, but I got a lot of feedback from other composers, and that is really important. One of the first was Colin Matthews, who sent me an email a few days ago. He was so happy! I could read in his letter this whole sense of what he had gone through with the Mahler Tenth. I strongly believe that – be it gradually – there will be more and more conductors and orchestras performing the ‘full’ Ninth, and it will be fascinating to watch what the response will be, and how it will progress.”

Wonderful moments “Working with Ben Cohrs on this was an extraordinary experience. This is also what he is: an extraordinary character. A brilliant, very dear and very generous man with no social graces. Does this not remind you of a certain Austrian composer? No one can dispute his knowledge and that he spent a lifetime with this. I have learned an enormous amount from him and I am very grateful for that. An incredibly bighearted man, with his willingness to share his knowledge and his time. That is something we all need. Daniel Harding feels absolutely the same. We appreciate that Ben is as complicated as many composers are. Some are wonderful to work with, like John Adams and once Witold Lutoslawski, ‘normal’ people so to speak, as many are not.”

“It was also a wonderful moment sitting with John Phillips. What an experience! When he told me where he finally found the sketches for the coda he simply started to weep. That was such an important moment for him, and how this began to flourish in the rehearsals and performances. These musicologists had spent so much time and effort, had shed so much blood and so many tears that I have to say: my deepest respect. I had heard the name of John Phillips for so many years and I imagined a taller, greyer, pale, the appearance of someone who had spent his entire life in libraries, not having seen the sun. When this guy walked in to the Berlin Philharmonic rehearsal in his ‘muscle vest’ I realised: how wrong can one be! As with anything else, you revise your prejudices.”

“Bringing all four of them, Samale, Mazzuca, Phillips, Cohrs, to stage after the first concert. I explained that this was the first time that they were physically all together, that this was a very moving moment. One of the horn players said: ‘These are about as different a quartet of people as you can find on our planet’. All united by this crazy, magnificent idea!”

___________________________ *Released on SACD by BMG/RCA (catalogue No 82876 54332 2)

By Aart van der Wal, www.opusklassiek.nl