Puccini, Turandot: (Revival Premiere) Soloists, Chorus and Orchestra of Welsh National Opera, Wales Millennium Centre, 28.5.2011 (LRK)

Cast:

Calaf – Gwyn Hughes Jones

Mandarin/Executioner – Martin Loyd

Liù- Rebecca Evans

Timur – Carlo Malinverno

Prince of Persia – Michael Clifton-Thomson

Turandot – Anna Shafajinskaia

Ping-David Stout

Pang – Philip Lloyd Holtam

Pong – Huw Llywelin

Emperor Altoum – Paul Gyton

Production:

Conductor – Lothar Koenigs

Director – Christopher Alden

Revival Director – Caroline Chaney

Designer – Paul Steinburg

Lighting Designer – Heather Carson

Lighting Realised by Paul Woodfield

Chorus Master – Stephen Harris

It’s always a tough call making sense of Turandot because it’s never the happy – ever – after romance that audiences seem to imagine. It isn’t verismo opera either in Puccini’s usual sense and it’s only by stretching the imagination a very long way indeed that the plot can seem to relate to the modern world. In 1994 however, when this current production was new, Christopher Alden begged to differ about that.

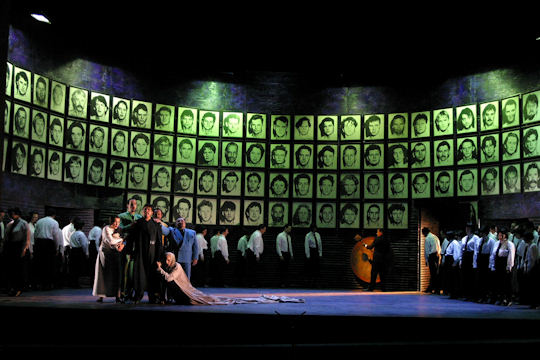

Alden thinks that Turandot is actually a disguised attack on fascism so there’s no fancy Chinoiserie here. Instead the action takes place in semi – circular room made of corrugated iron, unfurnished except for two or three chairs and pictures of Turandot’s victims on its walls. These Populo di Pekino are literally and drably uniformed, dressed in white shirts and ties matched with black trousers or skirts, the women with severe bobbed hairstyles and the men with goatee beards. This is a grim place indeed in which colour appears only in Ping, Pang and Pongs’ bright green, yellow and blue business suits and in Turandot’s blue velvet two piece. The Principessa herself looks like a cross between Hillary Clinton and Margaret Thatcher.

In contrast to these twentieth century figures, both the Emperor and Timur wear robes and crowns which seem to relate them both to some lost world superseded by Turandot’s merciless grasp on power. Liù’s costume shows that she belongs there too while Calaf occupies a separate territory of his own: in his drab greatcoat he has no apparent connection in either direction.

So the world of this Turandot is a seedy slaughter-house in which the Prince of Persia goes to his death orgasmically, being fondled suggestively by members of the crowd on his way to the headsman and ecstatically writhing around the executioner’s spear. The concubines seem to be stout middle-aged ladies in pyjamas suggesting yet again that sex and death are very nearly all of a piece here; hardly an original idea but one still relevant to Alden’s vision.

All of these allusions create problems for the opera’s final act of course, where the text appears to propose that Turandot will be permanently redeemed by Calaf’s love, however unlikely that might have seemed earlier. Alden’s vision is potentially very convincing at this point because it highlights the fact that the effects of total power (which will presumably pass sooner or later from Turandot to Calaf ) cannot simply be undone by marriage to an outsider, however vigorously he proclaims his noble motives. What is obvious after a moment’s thought is that these newly-weds are certainly not about to settle for 2.4 children , a Volvo and a place in the country. Calaf’s only recourse in this situation – and perhaps even his true purpose all along – seems very likely to be dealing with his new wife in exactly the same way that she treats everyone else : with total domination and probably some violence, controlling her completely before she turns on him to do something very nasty indeed. When fascism comes marching through the door, almost all romance will fly quickly out of the window

Despite its interesting ideas, the production has some difficulty knitting all its elements together neatly. Calaf seems not so much determinedly committed as bewildered; the old kings dodder and tremble so persistently and in so palsied a manner that they become distractions rather than characters essential to the plot. Liù plays her part appropriately enough, but the stylised torture and her death don’t come across as all that tragic, or even particularly sad. Generally, the disparity between what the characters are saying, what the music is implying and what is actually happening on stage feels much too obvious. The gaps in the overall logic are too big and lead to discomfort which has nothing to do with watching a shibboleth being seriously challenged.

Musically, the first act on the opening night was somewhat ragged, with an uncommitted feel from the chorus and a tendency for the principals to be drowned by the orchestra – at least from where I was sitting. This had cured itself by the second act (as so often happens) but we had missed out on some of the finest music in the opera.

Both Anna Shafajinskaia as Turandot and Gwyn Hughes Jones as Calaf were mainly in vocal control of their roles and, apart from the difficulties with volume, were a real pleasure to hear. As usual ‘Nessun Dorma’ was ecstatically received by the audience, this time with reason and ‘In questa reggia’ was sung in fact with considerable beauty.

Rebecca Evans’ Liù, whilst being convincingly sung with ease and finesse, did not feel as engaging as the character should , a problem that can be attributed to the direction as a whole. Among the Masks, David Stout stood out as Ping and received the loudest ovation from the audience while his colleagues came over as under-powered by comparison.

Apart from their performances in the first act, the chorus and orchestra were, as one expects from WNO, excellent, with Lothar Koenigs taking the opera along with considerable energy and with only the Act I problems already mentioned as noticeable blemishes .

On the whole, this was an interesting revival to revisit, even though not wholly engaging. For me it raised the usual distracting questions about Puccini’s operas: why on earth do people insist that Butterfly, Tosca and Bohème are fluffy romances rather than noticing all the horror and madness in which the composer specialised, and how is it that so many audiences simply never realise that La Fanciulla is full of truly wonderful music as a well as having a Genuinely Happy Ending?

So after an evening more of reflection than wholehearted enjoyment of the music, I concluded that although Christopher Alden quite rightly highlighted the cold-hearted horror of total power in this Turandot, Puccini’s operas only really work for most people when the verismo is skilfully concealed. For this illusion to be convincing, the more traditional productions and the music often do conspire to spin out the fantasy of romance and even in cases when only the music is good enough, then people still whistle the tunes on the way home..

The approach used by this production however could very easily have worked to deny the fantasy completely if only a little more attention had been given to important details. Then it might have left us with the sort of ambiguities that are hinted at by Luciano Berio’s 2002 ending to this admittedly difficult opera. That would have been a very great achievement for Christopher Alden and his team, perhaps even something unique.

Here however the audience gave the performance an explosive standing ovation, exactly like those awarded to competent orthodox performances. That’s the effect that Puccini himself might have predicted, I suspect, but I can’t help wondering if it might also have been something he would have rejected, if only he had been able to complete the opera himself.

Lyn Kenny