Italy Puccini, Madama Butterfly: Orchestra and Chorus of Teatro dell’ Opera, Pinchas Steinberg (conductor ), Rome, 23.2.2012 (JB)

Italy Puccini, Madama Butterfly: Orchestra and Chorus of Teatro dell’ Opera, Pinchas Steinberg (conductor ), Rome, 23.2.2012 (JB)

Production:

Stage Director – Giorgio Ferrara in co-production with Teatro Massimo, Palermo

Set – Gianni Quaranta

Costumes – Maurizio Galante

Lighting – Daniele Nannuzzi

Chorus Master – Roberto Gabbiani

Cast:

Cio-Cio San, called Madama Butterfly – Daniela Dessì

Lieutenant B.F. Pinkerton – Alexey Dolgov

Sharpless, American Consul in Nagasaki – Audun Iversen

Suzuki, Servant to Butterfly – Anna Malavasi

The Bonze, a priest and uncle to Butterfly – Alessandro Spina

Anthony Burgess once tried to persuade me that Luciano Berio was not really a composer at all but a supremely gifted creator of musical theatre, whatever form (vocal or instrumental) his compositions took. I said that I thought this was something of an exaggeration and you could just as well say the same of every other Italian composer from Claudio Monteverdi to Sylvano Bussotti. Anthony smiled his kindly smile, then said that he thought it was me that was exaggerating. Well, maybe. But he conceded that in the case of most Italian composers it was impossible to separate the music from the theatricality, since the two were so intricately interwoven as to be one.

Nowhere is the case clearer than with Puccini. He never misses a theatrical trick. But wait. Wasn’t that a musical trick while you weren’t looking, so to speak? The supreme art of deception –a deception we willingly submit to – is the working force here. Puccini, the master seducer. Those memorable, seductive soaring melodies fit the drama like a glove as it unfolds.

The opening of Madama Butterfly at La Scala in February 1904 was a fiasco. The show simply didn’t hang together and the second of the two acts was wearisome for its length. That is astonishing for the Puccini we all know, who is the world’s supreme hanger together of operatic plot and is never ever wearisome. So Puccini reworked it, cutting out material and adding new, and recasting the opera in three acts. In this reworking, for Bergamo in May 1904, and with a new cast, it fared better.

But still, all was not well. Ever the thoroughgoing professional, Puccini continued with alterations. Covent Garden got a new “edition” in 1906, then further changes were made for Paris in 1907.

The result is that since Puccini’s death, opera houses have felt at liberty to make free use of all this varying material, thereby effectively making each presentation a new “edition” of the opera.

The Rome Opera has chosen to return to the two acts, with a short first act and an interminably long second act. In reality, that second act is only a little over an hour; it is just that it feels like eternity when you are sitting through it. Puccini recognised this for his Bergamo revision. But the Rome Opera did not. And so we were punished accordingly. And I have worse to report.

But first let me turn to the positive features of the show. This is a co-production with the Teatro Massimo of Palermo and it is beautifully dignified in Giorgio Ferrara’s restrained stage direction. Butterfly is an opera in which much of the drama is brought about by what doesn’t happen. The problem is how to stage this without boring the audience blue. A movie director would have an easier task with access to close-ups. But all credit to Ferrara in freezing the action in such a way as to freeze our souls experiencing this wanting.

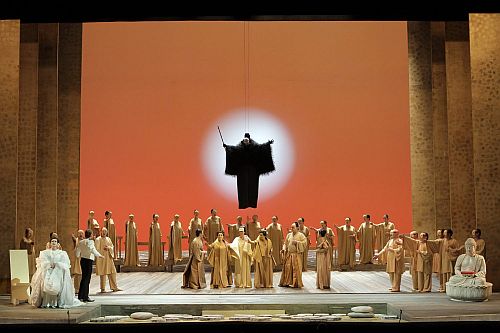

Flying in on wires, Butterfly’s uncle, the Bonze (a priest) who denounces the wedding at the end of act one, may sound gimmicky. But it works. For it to work, the audience should be shocked. Ferrari found the perfect way to stop the action with dramatic movement. This is profoundly respectful of the composer’s requirements. See photo. The simplicity of line of Maurizio Galante’s costumes had scarcely any reference to the Orient, as did the fine austerity of Gianni Quaranta’s minimalist set. Austerity is the very core of this drama.

Moving the chorus as though they were one was also an inspired choice. As singers, they delivered well, especially in the wordless, offstage chorus which comes hauntingly in act two in this edition.

Pinchas Steinberg is no stranger at the Rome Opera and the theatre’s fine orchestra respond well to his clear baton. All the oriental touches of orchestration were subtly realized without any resource to exaggeration. His tempi were admirable and in ordinary circumstances would have kept the show moving. But there were vocal problems which were insuperable.

Alexey Dolgov as Pinkerton was easily the most accomplished of the singers. He is athletic of voice and movement with an appropriately dashing stage presence. Amore o grillo was eloquently delivered, with a voice lighter than usual but decidedly secure in his presentation. He was handicapped in the big love duet at the end of act one by the protagonist. And so were we.

Daniela Dessì was truly atrocious. Although she is only fifty-five, if we are to judge by this performance, she has passed her use-by date. It is not so much that she places her notes, as scoops them from somewhere below, upwards, until only managing to arrive at some point above or below the note printed in the score. A shot at intonation, which fails to reckon with reality. That long second act is almost all hers. The voice was out of control from start to finish. She remains a beautiful woman and moves well. But in this production, as already explained, she is called upon to do little of this. The essence of the part is Butterfly’s delicacy. But Ms Dessì took a sledgehammer to the role.

Alessando Spina made the right chilling effect as the Bonze and Audun Iversen was adequate as Sharpless as was Anna Malavasi in that thankless role of Suzuki.

But you can’t really take off without a Butterfly.

Jack Buckley