United Kingdom Beethoven, Grew, Ryan, Miranda: Ten Tors Orchestra, Simon Ible (conductor) Theatre 1, Roland Levinsky Building, Plymouth University, Plymouth. 23.2.2013 (PRB)

United Kingdom Beethoven, Grew, Ryan, Miranda: Ten Tors Orchestra, Simon Ible (conductor) Theatre 1, Roland Levinsky Building, Plymouth University, Plymouth. 23.2.2013 (PRB)

Beethoven: Symphony No 7 (2nd movement)

Nicholas Grew: Self Portrait No 1

Nick Ryan: As above, So below – parts 1 & 2

Eduardo Reck Miranda: Symphony of Minds Listening

Peninsula Arts operates from within the Faculty of Arts and serves as the arts and culture organisation for Plymouth University, the largest university in the South West of England, and recently shortlisted as one of six finalists for the University of the Year accolade, in the annual Times Higher Education Awards, which eventually, in fact, went to its closest neighbour, the University of Exeter.

The year-round cultural programme includes music, exhibitions, film, public lectures, and theatre and dance performances. One of its musical highlights is the annual Contemporary Music Festival, promoted in partnership with Plymouth University’s Interdisciplinary Centre for Compute Music Research (ICCMR).

As well as creating a platform for music emerging from research, this year’s festival – ‘Sensing Memory’ – explores the theme of memory as a virtual sixth-sense, through inward journeys of the human brain and the pursuit of lost memories of childhood, forgotten ancestors and global connections.

The theme is, in fact, allied to a new four-year ICCMR research project led by Plymouth University’s Professor Eduardo W Miranda, and Dr Slawomir J Nasuto at the University of Reading’s Cybernetics Research Group. The project aims to create an intelligent musical computer that can help someone adjust their emotions when they are depressed or stressed: the computer will play music analysing the person’s brain activity as they do so, allowing it to select what sounds to generate based on how close the person is to feeling the way they want. The research will impact on the health and entertainment industries, such as the gaming fraternity.

This somewhat lengthy preamble is intended to put the festival’s pivotal concert into context, especially in terms of its programme, and its performers, Previous such events have tended to appear less homogenous, where the juxtaposition of computer-generated sounds and music with essentially purely acoustic works, hasn’t always felt altogether comfortable, and where it is less easy to assemble an audience equally tolerant or versed in these two quite different genres. The unmitigated success of this year’s concert with its predecessors is all down to programme planning, something at which conductor and Festival co-director Simon Ible, himself Director of Music at Peninsula Arts, is a past-master.

The Ten Tors Orchestra, resident professional ensemble of Peninsula Arts, Plymouth University, is arguably far more at home in classical and romantic repertoire, but its performers are sufficiently accomplished and adaptable to tackle contemporary scores with some panache, too. In fact, it’ is this orchestra’s multi-functional stance that continues to underpin and hopefully ensure its survival during straightened financial times.

Given this, it did not seem so incongruous that the evening opened with the slow movement from Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony Indeed, in previous stand alone concerts, there has been the occasional introduction of a single contemporary work or two, and one especially connected with the university and its associate composers.

Following a nicely-poised reading, Ible went on to explain how the Beethoven Allegretto would form the basis for the evening’s substantial work, Symphony of Minds Listening, to be heard in the second half.

Miranda had created this three-movement work of symphonic proportions by applying to the original Beethoven score what our ears do when we listen to music ourselves. In essence, by analysing brain activity from three quite separate individuals – a ballerina, philosopher, and himself – he fashioned each movement in the light of their respective responses.

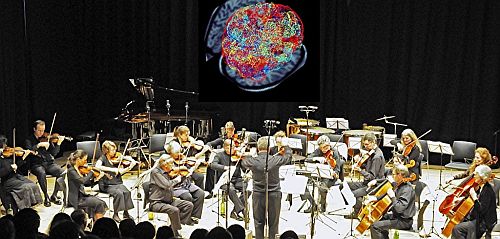

To the accompaniment of projected moving images of the brain impulses of these three people, the music unfolded seamlessly, and where, certainly at the start and finish of each movement, there was always felt a strong connection back to Beethoven’s original, in terms of timbre, key and layout.

Within the three sections themselves, subtle balletic traces emerged in the first, with an unmistakable trace of Latin temperament permeating the finale – not altogether surprising given Brazilian-born Miranda’s musical heritage. Less immediately appealing, the philosopher’s contribution had perhaps enjoyed less musical filtering or ordering in the transcription stage – or perhaps the responses had just been that much more convoluted. The effect was that the ensuing translation into sound felt that much more ‘difficult’.

For an in-depth insight into the compositional methods employed, readers are invited to read more about the work at http://neuromusic.soc.plymouth.ac.uk/

Nicholas Grew’s Self Portrait No 1 is a wonderfully evocative score. The composer himself writes: ‘(The work) is a set of variations for string orchestra, which is built upon fragments of music I have loved and known intimately at various stages in my musical upbringing and career. The piece uses seven fragments from Gershwin to Bartók, Sibelius and Stravinsky to Purcell. The original sources are only fleetingly recognisable before they are immediately transformed through a variety of compositional techniques to create a kind of emotional map or collage’.

The composer, currently residing in New Zealand, has lived in many countries around the world since his teens, and Self Portrait No 1 successfully emerges as a musical representation and chart of his travels, with many poignant moments, as well as setting the listener a continual challenge to identify each ‘snippet’. But it but which never suggests some kind of banal ‘potpourri’ – altogether an eminently listenable and enjoyable piece of contemporary writing.

The first part of Nick Ryan’s emotionally-moving As Above, So Below, inspired by the tragic loss of the composer’s father in an accident on a tea plantation in Kenya, in 1973 when Ryan was just six months old, had already been performed at a previous contemporary-music event towards the end of 2012. The second part, heard for the first time tonight, was made in collaboration with film maker Tom Kelly following Ryan’s recent return-visit to the African country last month. The resulting orchestral score is based on a computer-assisted analysis and transcription of the tonal and rhythmic information present in a series of sound recordings of people and places Ryan made while in Kenya. The performance was synchronized to a projection of filmed and still footage.

Given that, intentionally, there is little or no conventional melodic or rhythmic structure which would normally infer a ‘story’, Ryan hopes that ‘The audience will interpret the sound through their own experiences to create stories of their own’.

As such this did seem to have the desired effect, and perhaps linked back to the work of American experimental composer John Cage, whose 4’33” (1952) drew some equally undivided opinions at the time – whether it was actually intended to be complete silence and, as such, taking contemporary music at that time almost to the point of derision or whether it was a revelation in music-by-chance, where the sounds heard, which surround the audience on each and every different listening occasion, and, by association, the ideas and even ‘stories’ (albeit short of necessity) thus generated, are germane to its very conception.

Irrespective of the audience’s individual stance on contemporary music as such, this highly-innovative concert for once really did succeed in advancing the cause and perception of the genre, even among its more intransigent members.

For, while the thoughts of Miranda’s elected philosopher in Symphony of Minds Listening had seemed somewhat meandering at the time, when planning the programme itself, Miranda and Ible appeared to have looked more to Socrates for his input. Clearly by adopting his tenet – ‘from the known to the unknown’ – the message was not only well and truly imparted, but appropriately should also remain in the memory for some time to come.

Philip R Buttall