Finland Bartók Duke Bluebeard’s Castle / Leoncavallo I Pagliacci. Soloists, Finnish National Opera Chorus and Orchestra, Mikko Franck (conductor). Finnish National Opera, Helsinki. 12.4.2013. Premiere (GF)

Finland Bartók Duke Bluebeard’s Castle / Leoncavallo I Pagliacci. Soloists, Finnish National Opera Chorus and Orchestra, Mikko Franck (conductor). Finnish National Opera, Helsinki. 12.4.2013. Premiere (GF)

Casts:

Duke Bluebeard’s Castle

Duke Bluebeard: Vladimir Baykov

Judith: Niina Keitel

Bluebeard’s former wives: Diana Antoni, Jenny Björn, Nora Löfving (silent roles)

I Pagliacci

Nedda/Colombina: Helena Juntunen

Canio/Pagliaccio: Mika Pohjonen

Tonio/Taddeo: Jorge Lagunes

Peppe/Arlecchino: Aki Alamikkotervo

Silvio: Luthando Qave

Production:

Director: Vilppu Kiljunen

Sets: Sampo Pyhälä

Costumes: Mirkka Nyrhinen

Lighting design: Kimmo Karjunen

Judit – Niina Keitel, Siniparta – Vladimir Baykov Photos © Sakari Viika

Once upon a time it was almost obligatory to play the double-bill Cav & Pag on records and on stage. In recent times it seems that producers try to find new combinations. At Verona – well almost 25 years ago – the Mascagni opera was pared with Nino Rota’s ballet La Strada, Opera på Skäret combined Pagliacciwith Puccini’s Il Tabarro some years ago, the previous Duke Bluebeard in Stockholm found a suitable match in Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi – suitable insofar as they were almost contemporaneous compositions – and last year’s Bluebeard in Stockholm was in company with Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti. Strong contrasts and – in the Skäret production – closely related situations: a (rightly) jealous elderly husband finds proof of unfaithfulness and kills the wife and the lover (Pagliacci) or only the lover (Tabarro).

Jealousy is present also in Duke Bluebeard’s Castle but there it is Judith who frenetically wants to find out what is hidden behind the seven closed doors. What is revealed is frightening and when she at last opens the seventh door she expects to find the corpses of Bluebeard’s former wives. They are no corpses but not far from it, petrified, representing morning, noon and evening in Bluebeard’s life, and Judith is forced to join them, representing night. It is a creepy opera, spellbinding even when one knows the outcome, not dramatic in the external sense of the word – it was also rejected by the Budapest opera for lack of drama – but the psychological drama is the more tangible and it is just as much the music as the ‘action’ that conveys this. As a matter of fact this is an ideal opera to perform concertante and I still remember very clearly a performance in Stockholm Concert Hall more than 30 years ago, conducted by Antal Dorati and with two Hungarian singers. Libretto in hand this was the most nightmarish production of Bluebeard I’ve heard.

The production team in Helsinki have also skipped a realistic approach, the stage picture is rather abstract, only a steep staircase, down which Bluebeard and Judith enter, hints at an outside world, and it is partly removed when Judith has explored so much of Bluebeard’s secret that there is no return. Evocative lighting – it is a very beautiful production – good acting and singing and the playing of the FNO Orchestra is truly superb with Mikko Franck chiselling out all the subtleties and exquisite colours of this marvellous score, combine to make this a memorable performance. Niina Keitel, who is rapidly taking on big roles, was an eager and agitated Judith, with her darker timbre she sounded more determined than Paulina Pfeiffer’s younger and more innocent character in Stockholm last year (2012). There Terje Stensvold was an old but still imposing Bluebeard. Vladimir Baykov was younger and more dangerous. With Stensvold one knew that the eternal night was imminent, with Baykov one senses that he has to search for new challenges. But the staircase is broken …

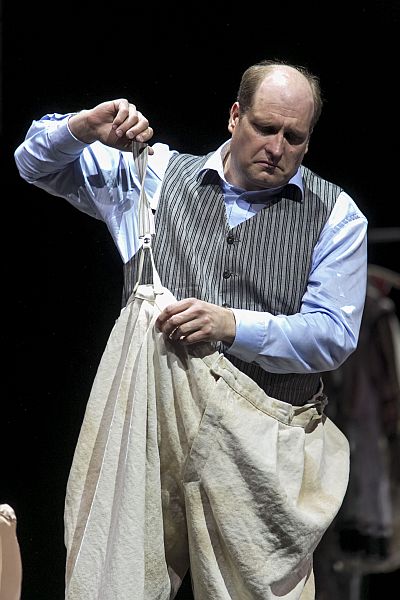

Canio/Pagliaccio: Mika Pohjonen

Photos © Sakari Viika

After the shimmering subtleties of Bartok’s music, Leoncavallo’s glaring score with primary colours applied with broad brush-strokes, feels like going to a secondary spaghetti-Western after an Ingmar Bergman film. But Leoncavallo’s aim – he wrote his own libretto – was not to describe dim otherworldly characters, it was to tell a story, from real life, of simple people with strong, sometimes primitive feelings that ends in catastrophe. The music is often noisy, fortissimo is the favourite nuance, but here and there some warmth creeps in. Nedda’s Stridono lassù with its colourful accompaniment, Tonio’s So ben che lo difforme reveals true feelings, not just a cardboard villain, and then the long scene between Nedda and Silvio, where Leoncavallo elevates the music to something above simple melodrama. Vesti la giubba always makes its mark in a good performance and there are other places too where the music is telling in a crude but honest way.

This production is obviously a rehearsal for a grand production of the commedia dell’arte play. Herds of stage workers, script girls and sundry others are gathered, including a conductor, score in hand and baton constantly waving, discussing tempos and other things with the actors. He is the spitting image of Mikko Franck and I imagine that Mikko must have mused down in the pit. Humour is omni-present in this production and the second act with the commedia dell’arte characters is almost grotesque: Nedda as Colombina is busty (Dolly Parton would look like a teenage girl by her side), Canio as Pagliaccio is over-obese and Beppe as Arlecchino is stripped to the waist and sporting a body-builder upper part, bursting with muscles – but match-thin legs. Against this the real drama, the crime passionnel between Canio and Nedda becomes even crueller.

I still don’t understand the end of the opera. After Canio/Pagliaccio has stabbed Nedda/Colombina to death and Silvio rushes to her rescue but remains halfway up a ladder to the scene of crime, the curtain is lowered in silence, there are sounds of movement behind the curtain and after quite a while Mikko Franck appears on stage in front of the curtain and announces La commedia è finita! and then conducts the final chords. No killing of Silvio. I’m still not certain if something went wrong on stage and I think the rest of the audience was confounded too.

Be that as it may, the performance was intense, a slackening of intensity in the scene after the Silvio-Nedda duet where Canio’s efforts to catch Silvio felt rather half-hearted. Acting and singing was on a high level. Mika Pohjonen has a true Italianate voice and he sang with an identification and intensity that was wholly convincing – and his acting was far better than I’ve seen before. Helena Juntunen made Nedda more cold and cunning than I can remember seeing before, her bird aria was technically accomplished but somewhat chilly but in the duet with Silvio she was marvellous. There her voice expressed true love. The young South African Luthando Qave was an excellent Silvio and his voice with an attractive quick vibrato reminded me of my first Silvio on records, Rolando Panerai. The Mexican baritone Jorge Lagunes was a great actor and his prologue was a good calling-card, a positive image that he more than lived up to during the rest of the drama. Aki Alamikkotervo added still one fine cameo role to his list of merits with a nuanced serenade to crown his achievement.

In sum two finely contrasted productions well worth a visit to the FNO. But I would like to know who was the conductor on stage.

Göran Forsling