United States Mendelssohn, Hindemith: Joshua Bell (violin), Christoph Eschenbach (conductor), National Symphony Orchestra, Kennedy Center Concert Hall, Washington D.C., 30.1.2014 (JFL)

United States Mendelssohn, Hindemith: Joshua Bell (violin), Christoph Eschenbach (conductor), National Symphony Orchestra, Kennedy Center Concert Hall, Washington D.C., 30.1.2014 (JFL)

Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto

Hindemith: When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d: A Requiem for those we love

I believe the National Symphony Orchestra and the National Symphony Orchestra deserve full houses. Encouragingly, that’s what they got on Thursday evening, January 30. With a program of Paul Hindemith’s When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d: A Requiem for those we love (never performed before by the NSO) and Felix Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, I suspect on this occasion the reason for the full house was rather the popularity of Mendelssohn’s work and the star power of soloist Joshua Bell’s.

Those who came for the Violin Concerto were not disappointed. Bell and Eschenbach were in sync throughout. Bell was the driver, but the trip was cushioned with the Cadillac suspension of the NSO strings. It was a well-balanced presentation, capturing the delicacy, warmth, and energy of the piece.

If the audience came for the Mendelssohn, it stayed for the Hindemith. Eschenbach has thrown himself into every choral piece I have heard him conduct—including Christoph Eschenbach and Dvořák’s Stabat Mater—with very good results. Some may not prefer his emotional emphases, but they are the product of conviction, not caprice. He clearly believes what he is doing, and usually brings me along with him.

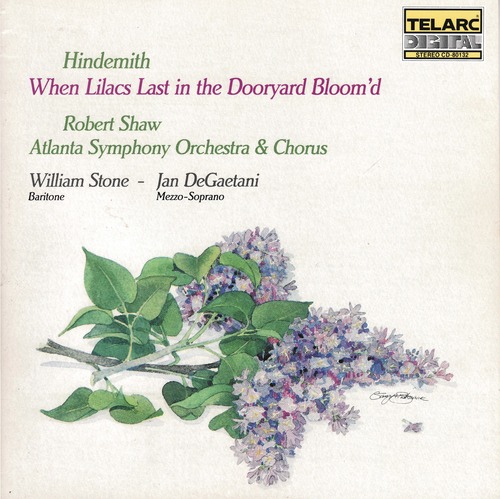

P.Hindemith, When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d, R.Shaw / ASO & Chorus / J.DeGaetani, W.Stone Teldec     |

He did so with Hindemith’s extraordinary work, aided and abetted by the very fine performance of the Choral Arts Society. The two soloists, baritone Matthias Goerne and the mezzo-soprano Michelle DeYoung, produced a mixed reaction for reasons having nothing to do with their excellent vocal abilities. The problem with When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d is the immensity of the text from Walt Whitman’s poem of that name. His memorialization of the death of Abraham Lincoln comprises more than 2200 words. That’s a lot to cover in a one-hour work. If you do the arithmetic, more than one word every two seconds (not allowing for the orchestral prelude).

Whitman is considered a quintessentially American poet writing about a quintessentially American subject. One then naturally expects to hear the words sung in what sounds like idiomatic American pronunciation. For DeYoung, who is an American, this was no problem, and she projected the text well. Goerne, meanwhile, does not sound faintly American: When his first solo began, my daughter wondered if he was singing in another language. He did not swallow syllables, but sometimes seemed to lose them altogether. Without the text in hand, it would have been impossible to follow him. The Choral Arts Society, as one might expect, was clear in its enunciation and projection.

Nonetheless, both the singing and the orchestral performance were very fine. The orchestral prelude expressed a wonderful solemnity, with excellent playing from the brass. The brass interjections in O western orb were also well executed. Everyone did well in the celebratory Introduction and Fugue, the latter part of which was electrifying—a tour de force. While many commentators will suggest Bach’s influence on this work, this part, along with the second verse of Death Carol, reminded me more of Vaughan Williams in his Sea Symphony—perhaps not so strange a comparison since Vaughan Williams was setting Whitman’s poetry in his work as well. In the latter part of section eight (Sing on! you gray-brown bird), the soloists’ voices were effectively intertwined. The “carol of the bird” achieved a kind of radiance that perfectly fulfilled the line which follows, which says, “the charm of the carol rapt me.” Indeed, it rapt me.

The work ends softly—appropriately enough for its subject matter—but this left the audience, which seems to have expected a concluding climax, confused. Unlike for the Mendelssohn, which received a rousing standing ovation, the audience remained seated and subdued— which simply reminds one that the quality of a performance is not necessarily correlated with the strength of the applause it receives. When Lilacs Last in the Door-Yard Bloom’d is not an easy piece and it requires large forces; one reason why it is not so frequently performed. (My own reservations about the work have less to do with Hindemith’s striking music than with the substance of Whitman’s world view. Pantheism can be good for the celebration of life, but only gets you so far regarding transcendence in death. That is because there is no transcendence in pantheism (by definition), leaving it incapable of dealing with the profundity of the subject matter of death in a fully satisfying way. There is a hollowness at the core of Whitman’s poem.) Still, it was certainly adventurous programming to pair it with the Mendelssohn, and those curious to hear it had better take this opportunity.

This program will be repeated on Friday and Saturday evenings, January 31st and February 1st.

Robert R. Reilly