United Kingdom Gurney, The Far Country: Philip Lancaster (baritone), Ben Lamb (piano), St Andrew’s Church, Churchdown, Gloucester, 3.5.2014. (RJ)

United Kingdom Gurney, The Far Country: Philip Lancaster (baritone), Ben Lamb (piano), St Andrew’s Church, Churchdown, Gloucester, 3.5.2014. (RJ)

Richard Shephard, There was such beauty: Lucy Hall (soprano), David Stout (baritone), Alan Parker (reader), Gloucester Choral Society, Cheltenham Symphony Orchestra / Adrian Partington (conductor), Gloucester Cathedral, 3,5,2014. (RJ)

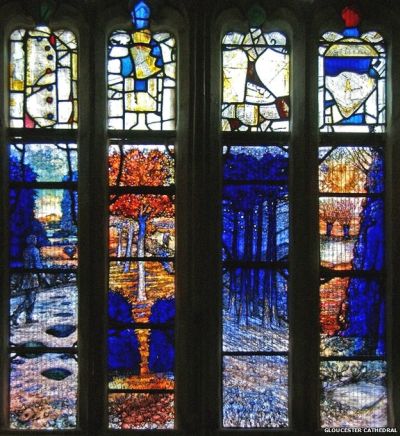

Photo (c) Tom Denny

Fate offered the composer Ivor Gurney a particularly raw deal. A gifted singer and musician in his youth he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London where he was hailed as “the English Schubert”. But then war broke out and like many of the young men of that era he enlisted, thus putting at jeopardy a promising musical career. However, in the trenches he discovered another talent – writing poetry – and in recent years his reputation as a war poet has grown.

Alas he was never to enjoy the fruits of success. He was gassed at Passchendaele and his health, including his mental health, went into sharp decline. In 1922, in his early thirties, his family had him declared insane and he was sent to various mental asylums where he spent the last 15 years of his life. For decades he languished in obscurity, but things are finally changing. More of his works (poetry and music) are being published, biographies of Gurney have appeared and – even more important – his music is being performed and recorded.

In 2012 Iain Burnside wrote a play about him entitled A Soldier and a Maker with a generous helping of Gurney’s music and poetry included. 2014 promises to mark an even more significant turning point in his fortunes. Clive Flowers’ documentary The Poet who Loved the War was televised in March to much critical acclaim. Then on April 30th eight memorial windows to Gurney were unveiled in the Lady Chapel of Gloucester Cathedral where he had once been a chorister. Much of the funding came from concerts organised by (and starring) mezzo-soprano Sarah Connolly, a long-time resident of the area. Designed by Tom Denny the stained glass is inspired by some of his best known poems: Glimmering Dusk, The Stone-breaker, Brinscombe, Only the Wanderer, Pain, Servitude, To his love, To God and Song and Pain.

And with the commemoration of the First World War well under way Gurney is likely to feature prominently throughout this year and subsequent years – and not only in his native county of Gloucestershire. For instance, he is to be featured as the BBC ‘s Composer of the Week on BBC Radio 3 during the week beginning Monday June 30th (You are advised to check any changes to the schedule.); and on August 1st Gurney’s War Elegy will be performed at the BBC Proms in London.

It was therefore no wonder that attendees at the AGM of the Ivor Gurney Society were in buoyant mood as they strode into St Andrew’s Church, Churchdown to hear The Far Country, a sequence of Gurney’s poems and song settings performed by baritone Philip Lancaster and Ben Lamb (piano). Lancaster who combined the roles of reciter and singer – no mean feat – is a Gurney scholar who has been working with the Gurney Estate to bring some of the composer’s important works to performance, recording, broadcast and publication. As if this is not sufficient he is a poet in his own right.

The sequence was devised with great care, each work leading seamlessly into the next as it explored the different facets of Gurney’s life: his love of the country, the experience of war and his dreamy waywardness. The opening poem April Gale was quickly succeeded by Gurney’s setting of Housman’s On Wenlock Edge, The Border Ballads by a setting of The Twa Corbies, Gloucester Song about the men who worked the soil by the familiar I with my father will go a-ploughing. But soon a darker tone interrupted this rural idyll with Autumn and the turbulence of Yeats’ Kathleen ni Houlihan. The rookscircling around prophesying woe in Omens served as a telling preface to Sassoon’s Everybody Sang. The death of a hero was dignified in Masefield’s By a Bierside. while Whitman’s Reconciliation brought to mind Wilfred Owen’s famous poem Strange Meeting. An element of escapism pervaded the latter part of the sequence – to The Lake Isle of Innisfree and The Far Country; later sleep and eternity. One could not fail to be moved by this 60 minute sequence – a tour de force by Philip Lancaster with sensitive accompaniment and supportive playing by Ben Lamb.

By a happy coincidence there was more Gurney that evening in a concert commemorating the First World War given in Gloucester Cathedral, which also featured music by Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Widor, Debussy and others. The work in question, There was Such Beauty, brings together selected poems by Ivor Gurney and his great friend F W Harvey (also a poet). Composed for orchestra, chorus, soprano, baritone and reader it is in three parts, of which the outer ones celebrate the Gloucestershire countryside and the inner one focuses on the First World War. It was premiered in 1991.

Like Gurney its composer, Richard Shephard, had once been a chorister at the Cathedral and is therefore well aware of the problems presented by the acoustics of the great Norman church. So I appreciated the clarity of his orchestration in the lyrical overture which evoked splendidly the rural scene while also generating undercurrents of uncertainty. After that came an eloquent reading of Gurney’s There was such beauty by Alan Barker and a joyful contribution from the chorus with Harvey’s A Roundel of Gloucestershire…….”of glory mellowing on the mellowing hills”. Two nocturnes followed: Harvey’s Over Bridge at Evening sung with clarity and sensitivity by baritone David Stout, and an exquisite Between the Boughs from soprano Lucy Hall.

In the central section a reading of Gurney’s Strange Service questioned why he had been transplanted from the English countryside to the battlefields of the Somme; after which conductor Adrian Partington whipped up his choral and orchestral forces in a terrifying evocation of battle. The day ends poignantly with a solemn requiem for warriors now asleep never to wake again.

Much of the final section is devoted to poems by Harvey, but Gurney’s Walking Song, slickly executed by baritone and chorus, brought life to the piece and seemed to epitomise the poet’s more positive qualities as a lover of country life. The final chorus, Harvey’s Musical Festival with its exuberant syncopated rhythms brought the work to an upbeat conclusion.

A good start! I think Ivor Gurney’s name will be on everyone’s lips before the year is out. His time has finally come.

Roger Jones