United Kingdom Puccini, Turandot: Soloists, Royal Opera Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House / Dan Ettinger (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 8.7.2017. (JPr)

United Kingdom Puccini, Turandot: Soloists, Royal Opera Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House / Dan Ettinger (conductor). Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, 8.7.2017. (JPr)

Production:

Director – Andrei Serban

Designer – Sally Jacobs

Lighting designer – F. Mitchell Dana

Choreographer – Kate Flatt

Choreologist – Tatiana Novaes Coelho

Cast:

Turandot – Lise Lindstrom

Calaf – Roberto Alagna

Liù – Aleksandra Kurzak

Timur – Brindley Sherratt

Ping – Leon Košavić

Pang – Samuel Sakker

Pong – David Junghoon Kim

Emperor Altoum – Robin Leggate

Mandarin -Yuriy Yurchuk

During Act III I was reminded of something I overheard several years ago when watching a previous Covent Garden Turandot, and someone said: ‘For most operas I like to leave before the last act and this is one of them’. It may have just been a coincidence that near me a person got up and left during Liù’s evocative funeral at precisely the moment Puccini ends and Franco Alfano’s completion begins. As most will know Turandot remained unfinished because of the composer’s premature death in 1924.

To digress even more, I can reminisce – as I usually do when reviewing this opera – about my historical connection to it as I knew Dame Eva Turner, one of the first Turandots (or Turandohs as she always pronounced it), as well as, Dame Gwyneth Jones, and often they talked about the demands of this fiendishly difficult role. Dame Eva was at the première of this opera in 1926 and first sang the role barely a few months later. She recalled once how the Maestro at La Scala said to her when she sang Turandot there: ‘Signorina I will give you the note after the “Straniero ascolta” ’ (this is when Turandot has to find the pitch for ‘Nella cupa notte’ in the first riddle). ‘Give me the note?!’ she replied, ‘If anyone has to give me the note, I’d be better off as a laundry woman. Indeed, they used to have an instrument – a sort of pipe – which could give the requisite note and I am glad I never needed it’.

Andrei Serban’s T’ai-chi-inspired production (in designs by Sally Jacobs and with Kate Flatt’s chorography) is revived by Andrew Sinclair and has returned for its 16th(!) outing since 1984 in remarkably fine fettle. The performance I saw that year was its 137th at the Royal Opera House, and now it has reached 275! I was intrigued to be reminded about the genesis of this staging – which has subsequently toured the world – in Sarah Lenton’s typically informative essay ‘Fresh as Paint’: ‘The current production was commissioned in 1984 as part of the Cultural Olympics in Los Angeles … a production team – who were fired – were followed by another production team – also fired. Suddenly the job landed on Kate, Sally and the director Andrei Serban. Time was obviously running out – some people in the Company will tell you they had only two weeks to turn it round, Sally Jacobs says she had at least six … The prominence of the dancers (and actors) is due to the fact there was no time to stage the enormous chorus, Sally Jacobs decided to set them in drum-shaped balconies.’

Much of the mise en scène was less familiar in 1984 than it is now from umpteen Chinese New Year celebrations, travel documentaries and movies originating in China. Familiarity can breed contempt, but ‘if it ain’t broke don’t fix it’, especially when the opera is as problematical as Turandot. Here apart from some processions and some ceremonial dancers very little does actually happen: Calaf, Turandot, Liù and Timur just walk on, around each other, or off, as appropriate. They always seem to me stock, one-dimensional, operatic characters and perhaps this was part of the problem Puccini had in finishing Turandot. Not even Plácido Domingo or Gwyneth Jones made anything of them in Los Angeles in July 1984, I understand, and nor did Ernesto Veronelli and Ghena Dimitrova, who I saw at Covent Garden a couple of months later. Occasionally singers ditch the original makeup and production. Here Roberto Alagna’s Calaf was not as white-faced as some of his predecessors; and he also brought back wonderful memories of the eccentric Franco Bonisolli – who did the exact same in 1988 – when he locked lips during a full-on assault of Turandot during the final scene. Its ended with them in a clinch on the floor of the stage and I don’t think that was in the original production, but it will look great when a performance is seen on the BP Big Screens on 14 July.

I thoroughly enjoyed the evening. With this opera I vacillate between wanting ‘blood and thunder’ or restraint from the orchestra; and although someone in the programme describes the opera as ‘conductor-proof’ …it isn’t! Dan Ettinger eschewed emphasising every climax and there were a surprising number of more chamber-like moments. I liked it when I heard the harp and some solo string lines that can often be missed, though on this occasion I wanted a bit more power and passion. Regardless this approach, once again, brought into sharp focus where Puccini’s invention ‘died’ and Alfano – with help from Arturo Toscanini – took over to complete the last dramatically implausible pages, as quickly as possible, musically. From the pathos of that funeral for Liù – after her sacrifice for her beloved Calaf – it is crash, bang, wallop downhill all the way to the grand explosion of the love-triumphant chorus (‘O sole! Vita! Eternità’) at the end. What made this an outstanding afternoon at the opera – it was a Saturday matinee – was the wonderful singing from all concerned in the second of two casts for these current eight performances. This included the enhanced chorus, who were on top form for their director, William Spaulding, and thankfully not as unremittingly loud as in the recent Otello.

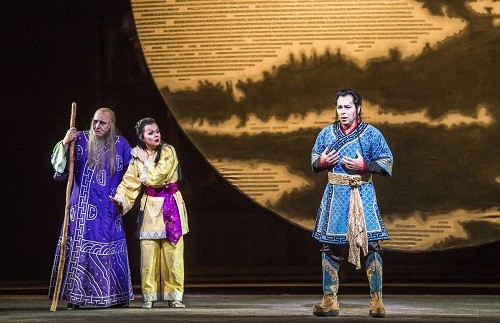

Like the Herald in Lohengrin, the Mandarin in Turandot can set the tone for the whole evening and here Yuriy Yurchuk’s forthright baritone made me sit up and listen. He was sturdily supported amongst the minor roles by Robin Leggate as Emperor Altoum, who seemed significantly less venerable than usual. Leon Košavić, Samuel Sakker and David Junghoon made up an energetic Ping-Pang-Pong trio and they sang expertly, even if they were not all at the same ease with the cavorting they need to do. For this short run their roles are double cast and so too is Timur, and it was something of a luxury to have Brindley Sherratt bring extraordinary pathos to the old king.

The role of Liù – even for any moderately accomplished soprano – is something that cannot fail given her two heart-wrenching arias. This was Aleksandra Kurzak’s role debut and what a debut it was! Even at the fringes of the action Kurzak never switched off for a second and was totally engaged in the performance. But it was the beauty of her sound that caught the ear and was at its very best during her uninterrupted confession to Calaf ‘Perché un dì, nella reggia m’hai sorriso’ and the steady stream of sound – poignant and heartfelt – culminated in a delightfully suspended piano.

It is probably easier to say where Lise Lindstrom hasn’t sung Turandot than where she has, which is an outstandingly impressive list. During her debut at Covent Garden in 2013 she sang her 100th performance of the role and it must be significantly more now. My thoughts about her then are much the same now; she has a vibrant, laser-like dramatic soprano voice, totally wobble-free, loud but not too loud. The opening bars of her entrance aria ‘In questa reggia’ – with its demanding tessitura – showed the qualities that would hallmark her entire assumption of Turandot: a well-focused, cold sound of inexhaustible intensity.

Roberto Alagna’s Calaf was the revelation of the evening for me. I have seen some fine performances on screen recently from him, but that is not the same as hearing a truly great singer live. (Maybe next time we can hear him in Keith Warner’s new Otello and it will probably be even better?) Calaf demands a spinto tenor with the reserves to leap to sudden high Bs and Cs; a challenge which Alagna met with consummate ease. He brought considerable vocal refinement to ‘Non piangere Liù’ and impressed with his technical security, strong, full, bronze-toned tenor. To add the extra frisson, we had a singer with his real-life wife on stage with him. Had Ettinger not pressed on as usually is the case after Alagna’s viscerally exciting ‘Nessun dorma’, it would have been a showstopper. As it was, the Saturday afternoon audience still burst into a few seconds of well-deserved, spontaneous applause.

Jim Pritchard

Jack Buckley has kindly sent this reminiscence:

Eva Turner had lived so long that it was hard to find anyone who had actually heard her sing. One such person was Alberto Testa, Italy’s leading dance critic who also much enjoyed opera.

Alberto had been present in his native Turin when Toscanini conducted ‘Don Giovanni’ with Eva as Donna Anna. The Zerlina was Magda Olivero (who died just a couple of years ago at the age of a 104!) Magda was the chair of the Treviso Competition for Young Singers in the Veneto in the name of her friend, Toti Dal Monte. I was on the jury of that competition for many years and at that point had not met Dame Eva. I’d always been curious about the SIZE of Eva’s voice and when I discovered Magda had sung Zerlina, I asked her if it was a BIG voice. Magda said that she didn’t remember it being particularly big, but it was exceptionally musical. She also remembered that Toscanini had complimented the English singer on her perfect shaping of Italian vowels and asked her how she came to have this perfection. Eva replied that it was because she came from Oldham and Lancastrians have this pronunciation naturally. (A story repeated by Eva when I later met her). When she was in Rome, being interviewed in Italian and English at the Teatro Ghione by Michael Aspinall, Alberto Testa presented her with a Medal of the Freedom of the City of Turin on behalf of that city’s fathers. (She had also sung Sieglinde in Turin.)

It was Michael Aspinall who had suggested I should get Eva to Naples when I told him that the British Council had just moved to new premises in Naples in Palazzo d’Avalos (Principe Francesco d’Avalos was a composer with his music sometimes performed by London orchestras). Michael pointed out to me that Eva had been one of first Turandots to sing the Alfano finale, which is how it has been performed for many years. I was the British Council’s Arts Officer at this time and getting together British cultural interest for the entry in the new premises. I got Sir Harold Acton (the Bourbon connection) involved – he was an excellent raconteur – and Richard Bebb agreed to accompany Eva, who was already well into her nineties but still as bright as ever. At a lunch in Rome which Michael Scott hosted, she had three conversations going on at the same time, something which I’m not able to do even now, not yet in my eighties. But above all she only agreed to come to Naples if she could revisit the San Carlo. That was easy to arrange. The Sovrintendente, Francesco Canessa, was a friend, and said he would be honoured. When we arrived there, there was a rehearsal of ‘Carmen’ going on, and we were shown into the Royal Box. As Eva sat, she immediately pointed out the box in which Alfano had sat when she premiered the opera there with his ending. She then also remembered a visit from Alfano after the show in which he thanked her for ‘that little change you made which I shall certainly incorporate into the new printed score’. This ‘little change’ was something Eva was offended about; she was always celebrated for her accuracy.

A little musicological puzzle for someone to solve there. Eva also told me that of all the Turandots she had coached, Ghena Dimitrova remained the most outstanding. Mine too.