United States Mozart, Così fan tutte: Lyric Opera of Chicago. Soloists Chorus, Lyric Opera of Chicago / James Gaffigan (conductor), Chicago. 17.2.2018. (JLZ)

United States Mozart, Così fan tutte: Lyric Opera of Chicago. Soloists Chorus, Lyric Opera of Chicago / James Gaffigan (conductor), Chicago. 17.2.2018. (JLZ)

Cast:

Fiordiligi – Ana María Martínez

Dorabella – Marianne Crebassa

Ferrando – Andrew Stenson

Guglielmo – Joshua Hopkins

Don Alfonso – Alessandro Corbelli

Despina – Elena Tsallagova

Production:

Conductor – James Gaffigan

Revival Director – Bruno Ravella

Original Director – John Cox

Designer – Robert Perdziola

Lighting Designer – Chris Maravich

Chorus Master – Michael Black

Lyric Opera of Chicago’s 2018 production of Così fan tutte boasts an international cast of soloists who bring their talents to some of Mozart’s most inspired writing for the stage. Familiar to Lyric audiences from other roles, Ana María Martínez was an engaging Fiordiligi whose acting is matched by her deft vocalism. She brought a welcome clarity to the well-known aria ‘Come scoglio’, with pitch-perfect leaps that showed her assurance. With even pitch and tone throughout the wide-range, Martinez rendered the melismas with delightful precision. Even more, her second-act aria ‘Per pietà’ was fittingly expressive, as Martinez held the long phrases to their full value.

As Dorabella, Marianne Crebassa sang well with Martinez, with the close-scoring in the ensembles demonstrating her rich mezzo. Playing Dorabella more extrovertedly than Martinez treated Fiordiligi, Crebassa used that approach to fine effect in the second-act aria ‘È amore un ladroncello’, in which Dorabella admits her indiscretion with Guglielmo. Crebassa’s sonorous voice fit well into this production, and nicely complemented Martinez, especially where the two singers matched ranges.

As Guglielmo, baritone Joshua Hopkins gave a full-voiced performance from the start. He contributed well-considered humor to the first-act aria ‘Non siate ritrosi’, with a welcome physicality. Hopkins’ warm sound benefitted from fine diction and articulation. In the duet with Dorabella, ‘Il core vi dono’, he was impressively impetuous.

As Ferrando, Andrew Stenson’s lighter voice combined beautifully with Hopkins, though at times Stenson’s tenor was difficult to hear in ensembles. Yet Stenson was impressive in his well-paced and phrased interpretation of ‘Un’aura amorosa’, including winning subtlety, especially in the closing, where he deployed a stylish diminuendo.

Alessandro Corbelli’s Don Alfonso was masterful throughout, as his sometimes parlando approach worked well in delivering the dialogue. His lyricism was equally strong, particularly the first-act trio, ‘Soave sia il vento’, which had the finesse of a studio recording. Alfonso’s arioso ‘Oh, poverini’, took the scene to a satisfying conclusion.

As his dramatic counterpart, the maid Despina was played exquisitely by Russian soprano Elena Tsallagova in her American debut. Tsallagova was impressive in her opening ‘Smanie implacabili’, balancing humor and lyricism. In the second act, her strong reading of ‘Una donna a quindici anni’ would have persuaded anyone to do what she requested. And when her character was in disguise, Tsallagova maintained pitch and declamation, a detail some sopranos miss.

The orchestra was led by James Gaffigan, also in his Lyric debut. After a brisk overture, Gaffigan settled into agreeable tempos. The performance was generally good, with a few places that might warrant a little more rehearsal for correct pitches and entrances. At times the balances in the pit were also off, with the brass sometimes dominating the rest of the orchestra. Yet Gaffigan honed the woodwind timbres, which are crucial to this score — a telling detail — and also made the transitions between recitative and orchestra flow effortlessly.

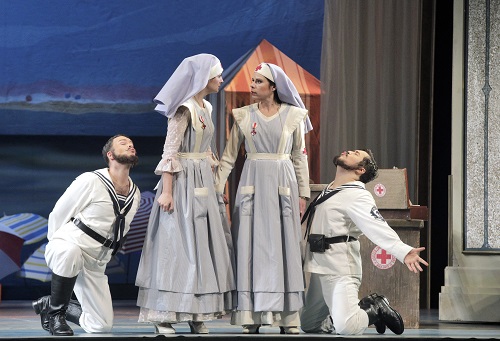

The production is the same one that Chicago audiences saw during the 2006–2007 season, and shared by the Opéra de Monte Carlo and the San Francisco Opera. Updated to August 1914, the World War I setting created an opportunity to garb the characters in period costumes. Yet some touches were problematic, such as the ominous stage fog at the work’s conclusion, and the introduction of supernumeraries in gas masks and other military paraphernalia. At the very point where the drama resolves, this dark touch seemed at odds with both the libretto and the score. After all, Da Ponte’s libretto is about human frailty and love, not war.

James L. Zychowicz