Germany Beethoven, Fidelio: Soloists, Sächsischer Staatsopernchor Dresden, Sinfoniechor Dresden, Extrachor der Sächsischen Staatsoper Dresden, Sächsischer Staatskapelle Dresden / Ádám Fischer (conductor), Semperoper, Dresden, 17.5.2018. (MC)

Germany Beethoven, Fidelio: Soloists, Sächsischer Staatsopernchor Dresden, Sinfoniechor Dresden, Extrachor der Sächsischen Staatsoper Dresden, Sächsischer Staatskapelle Dresden / Ádám Fischer (conductor), Semperoper, Dresden, 17.5.2018. (MC)

Cast:

Florestan – Tomislav Mužek

Don Pizarro – John Lundgren

Leonore – Elisabeth Teige

Marzelline – Tuuli Takala

Rocco – René Pape

Jaquino – Simeon Esper

Don Fernando – Christoph Pohl

First Prisoner – Torsten Schapan

Second Prisoner – Norbert Klesse

Production:

Production after Christine Mielitz

Revival Director – Bernd Gierke

Set and costume designer – Peter Heilein

Chorus master – Cornelius Volke

Premiered in 1805 at Vienna, Beethoven’s Fidelio is a revolutionary opera against oppression and political dictatorship and the demand for enlightenment, freedom and morality is still intensely valid today over two-hundred years later. The first Dresden performance of Fidelio was given in 1815 by the Joseph Seconda Theatrical Society. From 1823, first conducted by Carl Maria von Weber, Fidelio became a regular feature at Hoftheater Dresden, a strong tradition that has continued up to today.

Christine Mielitz had to push long and hard at ministerial level to achieve permission for this much-admired production of Fidelio to take place. It was premiered in October 1989 with angry sometimes violent political demonstrations taking place on Theaterplatz directly outside the Semperoper and in the city centre which was just weeks prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall. In effect the staging of Fidelio was a harbinger of the significant political events to follow. In fact, in some quarters Fidelio was seen as an analogy for the GDR revolution. Mielitz expressed the view it would it be inappropriate to pretend and dress-up Fidelio as being something other than what it patently is. She stressed that chief-of-police Pizzaro is convinced of his assignment. Mielitz stated ‘The piece is contemporary, it concerns us all… We cannot be cowardly; we must say what we must say. Nothing must be swept under the carpet.’

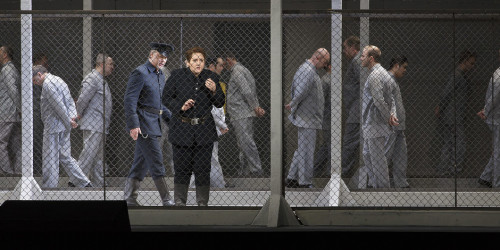

Positioned successfully on a revolve Peter Heilein’s set represents a bleak modern prison, painted predominantly in a dreary and rather irksome grey colour. The buildings include a high security wing, cells built into the high concrete walls, neon search lights and a central watchtower. The perimeter is ringed by barbed wire topped chain-lined fences. In the prison the audience could see into an open post-room where letters were censored and there was also a class room complete with desks and a row of batons hanging from pegs. Especially memorable was the scene of Florestan’s stark and gloomily lit dungeon. I am not sure if this is the idea of Mielitz or revival director Bernd Gierke but the opera opened and closed with a charcoal drawing on a large stage curtain, of a man upside down drinking from a bowl of water.

In the trouser role of heroine Leonore (aka Fidelio), Norwegian soprano Elisabeth Teige gave a solid performance and displayed her weighty, steady and attractive voice to significant affect, projecting her high notes remarkably well. An imposing figure dressed in a dark-blue prison guard’s uniform and black boots her natural stage presence was curiously underplayed possibly with the intention of not drawing attention to herself disguised as the young man Fidelio. Extremely moving was the scene where Fidelio by torchlight is helping Rocco to dig a grave intended for husband Florestan. Described on his website as the ‘black diamond bass’ René Pape as the prison governor’s henchman Rocco did all the role asked of him yet one felt he wasn’t as fully engaged as he might have been. Seemingly without too much effort Pape’s striking voice propelled easily through the house and I especially admired his degree of focus while his ability to move the listener was never in doubt. Decked out in a navy-blue uniform and black boots Rocco was constantly on the prowl, successfully coming across as a complicit and ruthless senior prison guard who one certainly would not wish to cross.

Leonore’s husband Florestan the nobleman specially imprisoned in a dungeon was sung by Croatian tenor Tomislav Mužek. This challenging role was tackled with aplomb by Mužek who with commendable clarity projected his engaging voice well and could impressively slide quickly to his top register. I am not sure why costume designer Heilein has Florestan, who had been imprisoned for two years and is in a dungeon, so well dressed in an expensive looking overcoat, waistcoat, white shirt and tie, surely his clothes would be in tatters. Swedish dramatic baritone John Lundgren excelled in the role of tyrannical, knife wielding, prison governor Pizarro who had incarcerated political rival Florestan and is starving him to death. Shaven headed and dressed smartly in a dark blue business suit, gold fob watch on chain with the choice of either a navy-blue or a camel overcoat Lundgren acted well strutting around menacingly and made a believably despotic governor. Undoubtably steadfast Lundgren’s deep and rich voice sometimes didn’t carry too well over the weighty orchestral writing. Minister of state Fernando, who read the pardon from the king, was sung well by Christoph Pohl the German baritone without making too much of an impression. Rocco’s daughter Marzelline and his assistant Jaquino played by Tuuli Takala and Simeon Esper gave solid performances and I would like to see them in more substantial roles.

I am not sure how often Ádám Fischer has conducted the Staatskapelle Dresden but their relationship was clearly a fruitful one. Fischer chose sensible tempi with a dynamic range that felt ideal. The orchestral players demonstrated their proven ability in such core repertory achieving a brilliant sound that was satisfying and appropriately dramatic. The individual contributions from soloists, too numerous to mention here, were out of the top-drawer. Under the coaching of Cornelius Volke, the combined choruses gave admirable and consistent performances although occasionally I required a little additional heft. In the concluding scene Mielitz positioned the soloists and chorus massed at the front of the stage singing the triumphant final chorus directly to the audience. It seemed pertinent that all this was carried out still behind the perimeter security fence which remained in place. For several years in my reviews I have been asking for English supertitles at Semperoper and this was my first visit since they were successfully installed, and I cannot thank Sächsische Staatsoper enough.

After nearly thirty years this Mielitz production still looks contemporary and fresh; it is certainly a production I would be delighted to see again soon. Beethoven’s Fidelio is a marvellous example of darkness turning into light especially in this enduringly successful Christine Mielitz production.

Michael Cookson