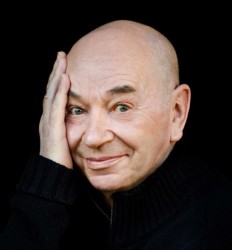

Lindsay Kemp (1938-2018): A Personal Tribute

There is hardly anyone working in theatre today – even those who have never heard of him – who doesn’t owe a debt to the inventiveness of Lindsay Kemp. Kemp’s search for theatrical expression. He studiedly broke down the barriers between mime, acting, designing, dancing, showcasing, vocalising, orchestrating and sundry other arts. It wove together comedy with tragedy, wordlessness with silence, extending an invitation to rethink what might yet be found on the other sides of theatrical expressions. He was by no means the first to understand comedy as the other face of tragedy, but he certainly made a unique contribution to that field.

Anyone who has not seen a Lindsay Kemp show should dedicate an hour watching Theo Eshetu’s film, Travelling Light – in part biographical, but mostly on the maestro’s art, with a commentary by David Haughton, forty-five years Lindsay’s collaborator. Nothing will ever substitute seeing Kemp in the theatre, but Theo’s film speaks Lindsayesque much better than my words. We offer this link (https://vimeo.com/168349166) courtesy of Travelling Light Productions. The film had one of its latest airings a couple of years ago at Tate Modern, in a Theo Eshetu retrospective.

The other side of life was where Lindsay’s aim lay. Aren’t we all? (aiming for that same objective) he once asked me in that characteristic wistful voice. Well now he’ll know: he died on 25 August 2018, age 80, in Livorno. Unusually he had lain down for a rest after lunch, closed his eyes and within minutes made a departure from life. As in life, in death. But I know that that is only the conventional reading of the other side. And yes, Lindsay had a remarkable distaste for the conventional.

That distaste also led him in turn, somewhat surprisingly, into parodies and jokes about the unconventional. He persuaded me about the usefulness of artifice as one of an artist’s main tools. Only one of the tools, he added. You really should get yourself a hat, he said, one chilly Rome morning in an exchange about keeping warm, it needn’t be feathers, it could be fruit, but don’t overdo it: better to start with just one or two fruits.

Wearing my hat as a British Council Rome Arts Officer, I wanted to involve Lindsay as choreographer for a stage version of Walton’s Façade with the reciters, for Walton’s eightieth birthday celebrations. Sir William lived on the island of Ischia and was a friend. A memorable trip to Ischia was arranged with Susana’s (Lady Walton) legendary hospitality.

Thanks to a lead from the Embassy’s Commercial Officer, we obtained sponsorship from British Leyland who were just launching a new car called the Maestro; Silvio Balossi, BL’s PR man, drove me down to Ischia in his Jaguar where we were greeted like royalty by William and Susana, and BL got some shots of Maestro Walton getting into the Maestro. In the meantime, I had been able to convince Francesco Siciliani – then in his third reincarnation as La Scala’s Artistic Director – to present the programme as part of La Scala’s season, though at a Milan theatre more intimate than the main house. Lele Luzzati came on board for sets and costumes. His work is best known in the UK for his Glyndebourne collaborations for Rossini and Mozart operas with Franco Enriquez’s stagings.

Façade is only forty minutes duration. So what to present for the second part? Lindsay wanted to explore Nijinsky’s madness – a project he’d looked at but shelved years earlier. This was revived in all its gripping horror and as a sharp contrast to the delightful soufflé of Façade. Audiences enjoyed Kemp explorations of the soul’s dark nights. Everyone remembers Flowers. And Nijinsky was no exception.

But my own preferred Kemp adventures with Death was his most poetic, looking at the life and death of Garcia Lorca, Duendi. This opens with near-naked monks flagellating on a set made up of a whole wall of flickering altar candles – forbidden by Italian law, but such a small detail never held Lindsay back – and tearing sheets of clothing from the life-size altar statue, which unmasks Lindsay/Lorca himself. Susan Sontag said she didn’t care much for this opening. Lindsay asked me to take her backstage at the end of the show. She must have spent ten or fifteen minutes reiterating all the literary influences she’d noticed in the ninety minutes of theatre. Lindsay would respond with such phrases as, Well you know how it is, and all the things you thought you’d forgotten come flooding back uninvited. As soon as she’d gone he asked me, had you heard of any of those writers she was rattling on about? I hadn’t. Neither had he, of course. But he knew what she wanted to hear. And gave it to her.

Susan tried to be helpful with suggestions for changes at the end of what the Italians call the anti-generale (full dress and lighting rehearsal, two nights before the opening) of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Romolo Valli, in whose Rome theatre, the Eliseo, this took place, made a particularly potent suggestion, There’s some good stuff here but what is missing is something which marks it up as Lindsay theatre. Something which could only be you: spitting blood, or whatever. (Lindsay played Puck as well as directing.) I could see he was bewildered by Romolo’s suggestion. I hadn’t wanted to intervene but I couldn’t either holdback: I know what you mean, Romolo, but might it not be that there are Lindsay hallmarks here which are making a first appearance, and for that very good reason, you don’t recognise them? That brought the suggestions session to a close.

At the end of the last dress rehearsal of A Midsummer Night’s Dream I had to miss a press conference because of a meeting at a Rome Ministry. The press conferences were always well attended. The journalists knew they would get a Kemp show improvised especially for them. I don’t remember whether it was at this press conference or another where when asked about Shakespeare he replied, well it’s all right, but there really are too many words.

He was right on that too. It wasn’t just Kemp impishness. Moreover, I was surprised to read in the press reports of the same conference that Lindsay was teaching courses for young actors. At dinner a few days later I told him that I didn’t know he was doing this teaching. I’m not, he said, I always make a few things up in those press conferences. Otherwise it gets too boring.

The Italian press treasured Lindsay’s gifts as a skilled improviser. He provided them with their best copy ever. For some of them his press conferences were his best shows. And all made up on the spot. This was particularly true of the country’s leading dance critics, Alberto Testa (La Repubblica), Vittoria Ottolenghi (RAI TV) Donatella Bertozzi (Il Messaggero) and others. He said, I invent myself as I go along. The British and American Press were not able to accept this. In the UK this made no difference to the audiences; most Kemp shows were sold out and with prolonged ovations. The critics in Spain were as effusive as the Italians and the Japanese were delighted to welcome Kemp recast in a distinctly Japanese mode. But even before the oriental influences, Tokyo audiences and critics went wild for both Flowers and Salomé.

The Spanish audiences would never allow him to drop Flowers from his repertoire and gave him years long residencies with this as a condition.

Lindsay was fond of telling how Marie Rambert had hit him over the head with her stick and told him to go back to the North, when he proposed the scenario for Cruel Garden – a part of the maestro’s infatuation with Lorca. If I’m not in love with a subject, I can’t do anything with it he said more than once. Cruel Garden went on to become one of Rambert’s biggest draws, even with the begrudging English critics.

Frederick Ashton was given his first work as a choreographer by Marie Rambert. I was a little surprised to see Freddy, as he was called in the dance business, present when the La Scala Kemp Façade/Nijinsky opened at Sadler’s Wells. The British Council with British Leyland organised a reception following the opening. Well the moment I stopped thinking of it as ballet, I found myself enjoying it, said Freddy, with a knowing twinkle in his eye.

Anton (Pat) Dolin was present too – much less surprised; a decade or more earlier he’d appeared at the Roundhouse in Lindsay’s Salomé as Herod – a part in which David Bowie would also later appear.

Also, Robert Armstrong was just back from Australia where he had been dispatched by the prime minister (he was her cabinet secretary) to prevent the publication of Spy Catcher. To do this he had to be economical with the truth for which trouble Mrs Thatcher made him a Life Peer. The Australian Court Scene could have been written by Lindsay. When I asked Robert what he thought of the show he replied with an ambiguous smile. Economical to the last.

I cannot end this tribute without mention of Lindsay’s most vital collaborator, the Spanish, Chilean conductor, pianist, composer, Carlos Miranda, whose career was started from a London base. He predeceased Lindsay by two years.

When I asked Christopher Morris (director of OUP Music – Walton’s publisher) what he thought of the Façade/Nijinsky double bill, he said, knowing that this would only be a dream, Carlos Miranda is the composer we should be publishing. The Nijinsky score is largely electronic music and Christopher knew he would never get his dream through his board.

Carlos and Lindsay met at Ballet Rambert where Carlos was already composer in residence. He would soon become resident composer and music director for the Lindsay Kemp Company. My most treasured memories of Carlos’s collaborations are Big Parade (an exploration of the silent movie scene) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

I would never invite Lindsay over to lunch without an aperitif of a 78rpm record of a Music Hall diva which would be new to his ears. It set the scene for more merriment and probably more wine than was good for us. But both of us were at one with Nigella Lawson’s assertion that all meals with friends should be a celebration. Big Parade scored high with me because of Carlos’s immense collection of Music Hall repertory.

But for A Midsummer Night’s Dream Carlos scored the band for Music Hall instrumentation, as well as teaching dancers – most of them untrained in singing- how to sing Mendelssohn’s Dream music. What a celebration!

Jack Buckley

For more about the life and work of Lindsay Kemp click here.

Brilliant xx

Not brilliant at all, dear Sylvia. But it’s the best I could cobble together with restricted resources (Whitgift School have still not unpacked my library which I have given them for use of the sixth form) and to offset some of the lies which appeared in some UK obituaries.

With the generous gift of Theo Eshetu’s film, I hope people who never met Lindsay or saw his work, will get some idea of what this meant and continues to mean in terms of theatrical invention.

Good to read you Jack, well said.

Had been thinking of you when in Rome for Lindsay’s funeral, and remembering you with Max there also.

All best wishes

Kris & Steve

Thank you Jack,

Your words capture and recall the mischievous spirit of Lindsay so very well.

A minor note: Did David Bowie really go on to play the part of Herod!?

Thanks again

Phillip

Thank you for some illuminating recollections Not my world but an interesting read as always.

You paint him so brilliantly . What a genius he was !

Lindsey Kemp left a deep deep impression on me as an 16 year old watching him as the Madonna, swaddled and swaithing in white material, white faced with a strange expression of agony /estacy to Mozart’s Laudate Dominum.

I’ve followed him ever since and that was in 1960…

No wonder he raised eyebrows of the conventional !

I’m in Rome today, has his funeral taken place yet?