United Kingdom Sibelius, Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky: Nicolai Lugansky (piano), Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra / Vasily Petrenko (conductor). St David’s Hall, Cardiff, 6.3.2019. (PCG)

United Kingdom Sibelius, Rachmaninov, Tchaikovsky: Nicolai Lugansky (piano), Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra / Vasily Petrenko (conductor). St David’s Hall, Cardiff, 6.3.2019. (PCG)

Tchaikovsky – Fantasy Overture: Romeo and Juliet

Rachmaninov – Piano Concerto No.3

Sibelius – Symphony No.5

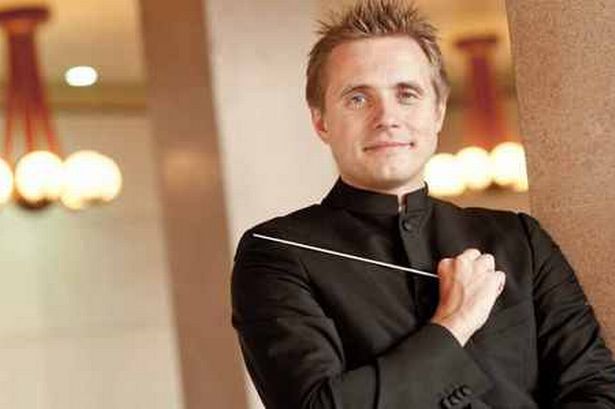

British audiences will be most familiar with the conductor Vasily Petrenko through his work as conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, a position he has occupied since 2006. Since 2013, he has also been chief conductor of the Oslo Philharmonic. He gave here the first in a season of five concerts as part of their current UK tour. He has obviously established a good working relationship with the players. This bore fruit in Cardiff, where three pieces from the standard repertoire were all given performances which were not only technically impeccable but also brimmed with fresh insights.

This was apparent from the very opening, when Tchaikovsky’s chorale (representing Friar Lawrence) was given a very solemn and stately rendition to begin the Romeo and Juliet Fantasy Overture. It is not clear that Shakespeare intended us to take the character himself very seriously, but Tchaikovsky did, and this approach to the music paid dividends. The music slowly gathered momentum and pace until the music for the lovers themselves and the conflict between Montagues and Capulets erupted with all the passion that the subject requires. The battle sequences might have sparkled more brilliantly in other performances, but the playing of the strings had all the fizzing explosiveness that one could have wished. There is a good case for contending that the music here should be more menacing than simply spectacular. The work, which can sometimes disintegrate into a series of linked episodes, certainly held together as a symphonically conceived whole. Even the closing loud chords sounded less like a conventional conclusion than they can do.

Similarly revelatory was the account of Rachmaninov’s Third Piano Concerto, which at times a few years ago seemed set to become a regular annual fixture in concerts at this hall. The orchestra certainly delivered plenty of sparkle in both the opening and closing movements, and Nicolai Lugansky’s playing was quite simply incomparable. He made the composer’s barnstorming demands sound positively straightforward, which of course they are not. The sheer volume of sound he elicited from the piano never ever sounded forced or over-extended. He gave us the revised version of Rachmaninov’s first-movement cadenza (Rachmaninov himself preferred it when he made his own recording) but it was clear that he would have been equally happy in the plunging chords of the alternative version; and he rightly had no truck with the cuts that Rachmaninov himself made in the concerto. Timothy Dowling’s excellent programme notes attempted to justify some of the composer’s propensity for making cuts in his own music by citing instances when as a solo recitalist Rachmaninov would cut out segments if he felt his audience was getting bored. Such practical considerations (like the need to fit the music onto 78 rpm sides) must surely nowadays be overpowered by aesthetic ones, especially as the optional cuts in the second and third movements of this concerto remove pages of the score which are by no means inferior to those retained. Similarly, Petrenko preserved the skirling woodwind counterpoints in the finale, which Rachmaninov did mark in his score as optional, but which add to the dervish excitement of the writing. Lugansky began the finale at a daringly fast pace which might have left little room for manoeuvre later on, but the articulation was crisp and the later challenges by no means found him wanting. His encore, a Debussy Prélude, was then a perfect foil to the fireworks that had proceeded it.

After the interval, Petrenko provided plenty of insights into Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony. Time and again he revealed contrapuntal figurations that can often be submerged in the orchestration. He also showed a welcome willingness to stick to Sibelius’s sometimes surprising tempo directions – even when the composer himself might be unclear. (What is one really to make of the second movement’s Andante mosso, quasi allegretto, especially when the second part of the phrase is a later addition made during Sibelius’s revision of the score?) The grandiose theme in the finale, which Sibelius identified as a depiction of swans in flight, was maintained by the conductor at a granitic speed. That clearly challenged the orchestral horns and trumpets to their limits but produced a sense of stately monolithic progress which was clearly what the composer had in mind. Only in the final bars, where Sibelius allows for ‘un pochettino stretto’, did Petrenko allow the music to push forward to the detached final chords – and even then the acceleration was restricted to the ‘very little’ degree that the composer specified. The whirlwind passages of the scherzo ending to the first movement and the whispering string tremolos at the beginning of the finale, on the other hand, had all the sense of buzzing excitement that anyone could have demanded. Timothy Dowling’s extensive programme notes were again enlightening.

The large audience rightly erupted in cheers at the end and were rewarded with two encores. Morning from Grieg’s Peer Gynt obviously displayed this orchestra in their element, with a performance where the fluctuations of speed were often surprising but always idiomatic. The Brahms Hungarian Dance No.5 which followed was a sheer display of good humour.

The orchestra continue their tour with performances in Nottingham (7 March), Birmingham (8 March), Leeds (9 March) and Gateshead (10 March) with varying programmes but the same soloist and conductor. Those able to get tickets in those later venues should not hesitate.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

For more about the Oslo Philharmonic click here.

Excellent and accurate depiction of a splendid evening of music-making. Both conductor and soloist delighted everyone with this insightful concert.