United States 2019 Tanglewood Music Festival [6] – Koussevitzky Music Shed, Lenox, 19 & 20.7.2019. (CSa)

United States 2019 Tanglewood Music Festival [6] – Koussevitzky Music Shed, Lenox, 19 & 20.7.2019. (CSa)

19.7.2019

Betsy Jolas, Saint-Saëns, Debussy and Ravel: Gautier Capuçon (cello) Boston Symphony Orchestra / Andris Nelsons (conductor)

Betsy Jolas – A Little Summer Suite

Saint-Saêns – Cello Concerto No.1 in A minor

Debussy – La Mer

Ravel – La Valse

20.7.2019

Elgar and Kevin Puts: Renée Fleming (soprano), Rod Gilfry (baritone), Boston Symphony Orchestra / Andris Nelsons (conductor)

Elgar – Variations on an Original Theme, ‘Enigma

Kevin Puts – The Brightness of Light

Things were hot at Tanglewood, both meteorologically and musically, as the Berkshires sweltered in record temperatures and steaming humidity. The Boston Symphony Orchestra, under the sure hand of Andris Nelsons, brought us two works by contemporary American composers: A Little Summer Suite by Betsy Jolas, first performed in 2016 by Sir Simon Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic, and a premier performance of The Brightness of Light by Pulitzer prize-winning Kevin Puts.

Jolas, now 92, was a former pupil of Darius Milhaud and Olivier Messiaen and now resident in Paris. She describes her Little Summer Suite as ‘seemingly aimless …wandering music’, and it was this charmingly accessible 10-minute piece that opened the first concert. Structured like Mussorgsky’s episodic Pictures at an Exhibition, each of the seven movements has an explanatory title, such as Strolling away, Knocks and clocks, and Shakes and quakes. It is possible to imagine, in these brightly coloured musical paintings, the sights and sounds that greet the composer as she walks along the Left Bank, particularly Chants and cheers, with its plangent oboe obbligato and exquisite harp and glass chimes.

Unfortunately, the fans overwhelmed Gautier Capuçon’s vibrantly nuanced account of Saint-Saëns’s Cello Concerto No.1 which ended the concert’s first half. I refer not to the cellist’s dedicated and enthusiastic base, but rather to the industrial sized air conditioning units on either side of the platform whose disconcerting rumble made a good part of the performance simply inaudible. Mercifully, these were silenced after the interval, allowing us to immerse ourselves in the turbulent waters of Debussy’s La Mer. The BSO have been regularly performing La Mer since 1907, and few orchestras better evoke the sweeping shifts of movement and Turner-inspired refractive light in Debussy’s richly musical canvass. The opening movement – Dawn to Noon on the Sea – was beautifully articulated, particularly in the sensuous woodwind passages, while the strings shimmered enticingly in Play of the Waves. A visceral account of the last movement – A Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea, in which the BSO’s magnificent brass section and crystalline percussion penetrated the thick orchestral texture, brought the work to a triumphant close.

The concert ended with a heady, abandoned rendition of La Valse, Ravel’s ironic homage to the Viennese waltz. It is a matter for debate whether or not the composer intended this work as a metaphor for the disintegration of a decadent Austrian society after the ravages of the Great War. It is however, an apt metaphor for our times, as global warming threatens, the music plays on.

Temperatures were even higher for the following night’s concert in which Elgar’s Variations on an Original Theme ‘Enigma’ occupied the first half, and the world premiere of an adventurous BSO commission, The Brightness of Light by U.S. composer Kevin Puts, took up the second part. A common theme linked these two works: they are both musical depictions of portraits.

Elgar based each of his 14 sketches or variations on his friends, acquaintances and himself, to whom he referred only by initial. Their identities are now well known. If these oblique references were Elgar’s ‘enigma’ the code has long been broken. The first and most tender of the Variations – an Andante of ineffable beauty – is dedicated to C.A.E, the composer’s wife Alice. Nelsons drew out an expansive and deeply affecting account of Variation IX, Nimrod – a noble Adagio in which the strings, initially soft and hesitant, work their way to a gentle crescendo. It was difficult in the heat of the Tanglewood Shed to summon up the cool of the Malvern Hills so beloved by Elgar, yet the orchestra demonstrated its affinity with this most English of composers, and managed to tap the emotion and restraint which define his musical sketches.

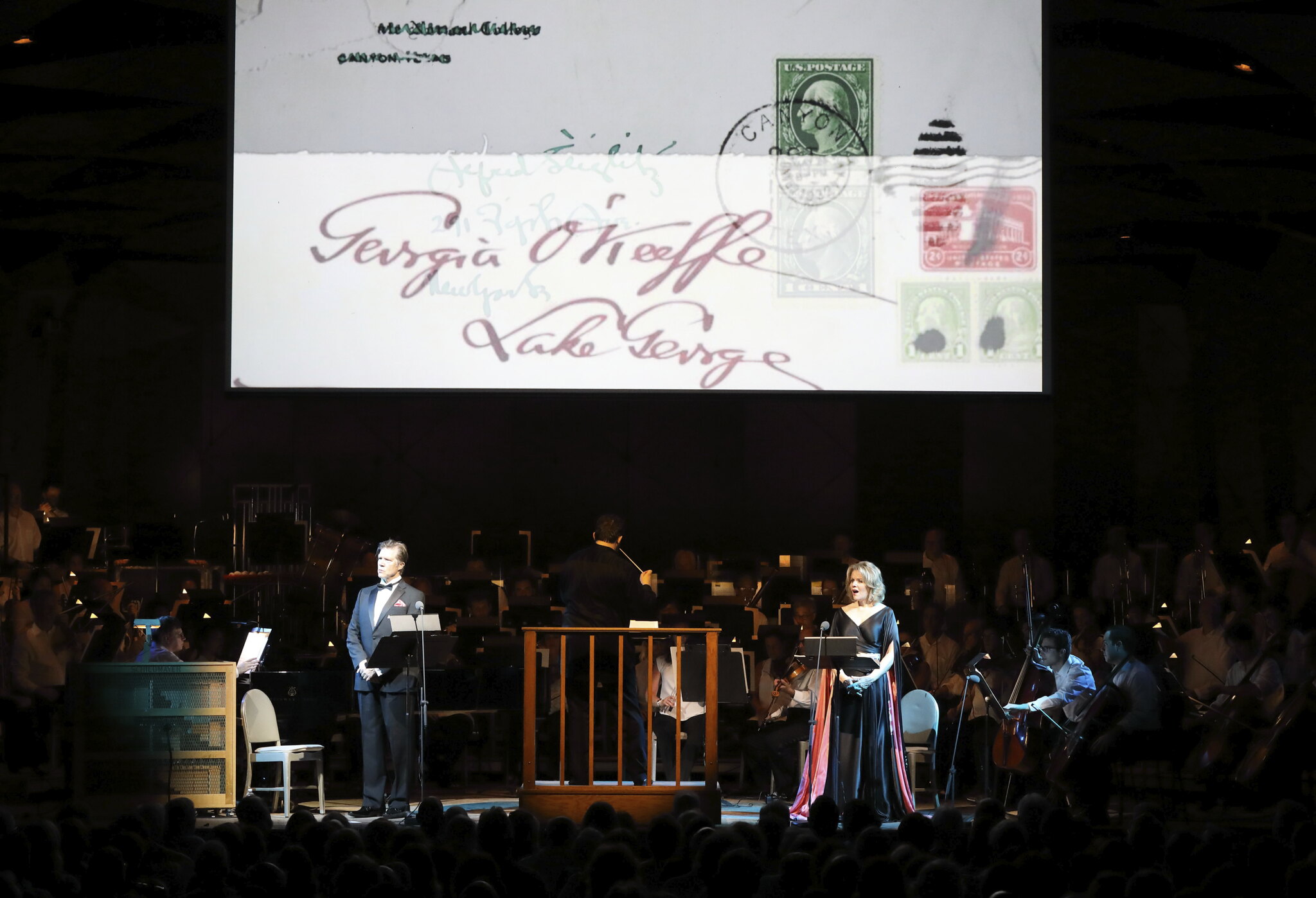

The Brightness of Light is described by the composer as a song cycle for soprano, baritone and orchestra, in which Puts sets to music an exchange of letters over many years between the iconic U.S. artist Georgia O’Keefe (sung by the great soprano Renée Fleming), and her errant husband, the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz (American baritone Rod Gilfry). The work’s title derives from O’Keefe’s claim that her first memory was of ‘the brightness of light – light all around’. She was also to acknowledge that ‘Since I cannot sing, I paint’. Puts’s musical depiction charts the evolving relationship between O’Keefe and Stieglitz – from the tentative early correspondence to the deeply passionate and painful love letters of later years. This was evidenced by, indeed reliant upon, some fascinating black and white photographs of both artists and by a show of O’Keefe’s sensuous paintings of flowers and brightly-lit desert landscapes, all of which were projected onto video artist Wendall Harrington’s overhead screen. Yet, on a first hearing at least, the music never really sang. Despite some delicate passages of finely coloured orchestration – and notwithstanding superb performances from the two soloists – Puts’s score was little more than a flat and prosaic accompaniment, doing little to heighten the rich lyricism of the letters themselves or the feast of visual images being beamed above us.

Chris Sallon