Germany Schubert, Mozart, Berg, and Widmann: Sarah Aristidou (soprano), Jörg Widmann (clarinet), Staatskapelle Berlin String Quartet (Wolfram Brandl, Krzysztof Specjal [violins], Yulia Deyneka [viola], Claudius Popp [cello]), Boulez Ensemble / Daniel Barenboim (piano, conductor). Pierre Boulez Saal, Berlin, 1.9.2020. (MB)

Germany Schubert, Mozart, Berg, and Widmann: Sarah Aristidou (soprano), Jörg Widmann (clarinet), Staatskapelle Berlin String Quartet (Wolfram Brandl, Krzysztof Specjal [violins], Yulia Deyneka [viola], Claudius Popp [cello]), Boulez Ensemble / Daniel Barenboim (piano, conductor). Pierre Boulez Saal, Berlin, 1.9.2020. (MB)

Schubert – String Quartet in C minor, D 703, ‘Quartettsatz’

Mozart – Clarinet Quintet in A major, KV 581

Berg – Four Pieces for clarinet and piano, Op.5

Widmann – Labyrinth IV, for soprano and ensemble

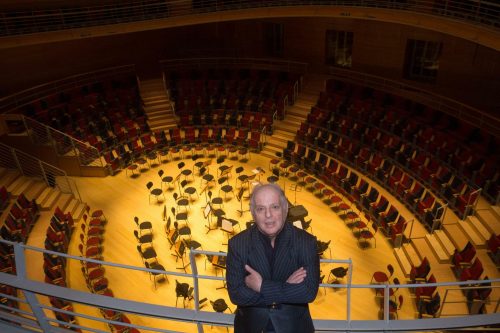

The new season at the Pierre Boulez Saal could hardly have opened in more promising fashion, whether strictly musical or in the hope imparted for the year to come. I was there at its predecessor’s premature close in March; so too was Daniel Barenboim, completing just in time his series of the Beethoven violin sonatas with Pinchas Zukerman. Here we heard Barenboim as pianist and conductor, but as part of a greater ensemble, of which Jörg Widmann was at least as prominent a member.

The first piece featured neither Barenboim nor Widmann, but rather the Staatskapelle Berlin String Quartet, in Schubert’s Quartettsatz. It works splendidly as a quasi-overture, not least to a programme such as this: ‘first’ and ‘second’ Viennese schools, themselves inextricably interlinked, with a contemporary successor who has long gained inspiration from both, as composer and performer. The Staatskapelle players offered a balanced and dynamic reading, alert, even febrile, so as to draw one in not only to this piece but to the programme as a whole. Schubert’s instrumental drama already presented themes that with only a slightly tweak of melody or harmonic context would be at home in Berg. Growing unease led inevitably to the tragedy of a coda whose tragedy seemed also to be that of our present condition, albeit without an ounce of self-pity: rather, fate itself.

Such anxiety, often subtle yet all the more pervasive for it, was to be heard in Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet, for which Widmann joined the quartet. Mozart’s cultivated mastery might mask such feelings to incurious players and listeners, but as we now know very well, masking is a strange and defective thing. There was no question here in the first movement as to the importance of Mozart for his Viennese predecessors, Berg and of course Schoenberg among them. Developing variation and extraordinary balance in complex phrasing — how many even notice? — were miraculously achieved in work and performance, proceeding in unfussy yet variegated fashion at a well-judged tempo. The drama of the development presented instrumental intrigue to rival any operatic ensemble, resolving with equal mastery.

So too in the second movement, which seemed to speak of the Countess a few years on. Detailed playing from all concerned had Widmann first among equals, if that. Why could harmony not have stopped here? It seemed a question as necessary to ask as it was impossible to answer; as the Countess would have told us, time moves on, such being both the comedy and tragedy of the human condition. Cultivated, composed, resolutely unsentimental, the minuet’s view on life was enhanced by trios in tragic, then serenading dialogue with its material, the second seemingly from a world poised between Don Giovanni and La clemenza di Tito, a world that might spin out of control yet never did. Mozart’s balance between joy and melancholy was once more finely judged in a finale of metamorphosis through variation: a message there for all wishing to listen. Inevitability, in which the darkness of the viola-led variation (wonderful playing from Yulia Deyneka) necessarily bubbled over into the high spirits of the next, afforded further immersion in Mozart’s tragicomedy of life.

Melodies from Mozart and Schubert, or reminiscences thereof, however imaginary, haunted the pages of Berg’s Four Pieces for clarinet and piano, in a commanding performance from Widmann and Barenboim, each movement a labyrinth and scena of its own, which yet formed part of greater mysteries. Berg’s alchemy of melody and harmony came as thrillingly alive as had Schubert’s and Mozart’s, the frankly erotic charge stronger still. An expressionist chill of fate, culmination of a single yet multifarious breath, brought glowing, glistening, eruption, and death, and not only sequentially. This was a full-scale opera, or at least an instrumental drama, of its own.

Barenboim, the Boulez Ensemble (drawn from members of the Staatskapelle and the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra), and Sarah Aristidou gave the premiere of Widmann’s Labyrinth IV last year. I was delighted to hear it and look forward to deepening my acquaintance with a compelling work for soprano and ensemble which, if not quite a song-cycle, suggests elements of that great Schubertian tradition in its setting of texts concerning Ariadne and the Minotaur — no Theseus, no other mediator — from Euripides, Brentano, Nietzsche, and Heine. An opening primal cry signalled much: not least that vocal music, for the first time since March for me, was now also back on the agenda. Instrumental interjections, from double bass to drums to accordion, heightened the sense of a primaeval drama which, if owing no evident debt to Birtwistle, perhaps shared with his music that sense of a violent, unsentimentalised prehistory. In this case, Ariadne must confront her half-brother and indeed her mother, the first number eventually moving to Euripdes’ words: ‘O miserable mother, tell me why did you bear me?’ (in Greek). It was Aeschylus, perhaps, who seemed to speak in the music, though, at least according to the still-influential typology dictated by the author of The Birth of Tragedy (and, of course, his mentor and ultimate, unknowing antagonist, Wagner).

For the following ‘Kinderlied für ein Ungeheuer’, we heard indeed a nursery rhyme for a monster, Aristidou, a born singing-actress, circling the hall on its first level, looking and singing into the orchestral labyrinth itself: again, first music, only latterly with words. A neo-Bachian (via Second Viennese School) canon marked the ‘Gang ins Labyrinth’, Ariadne’s progress delineated by ensemble alone, the labyrinth, in proper Bergian sense felt as much as observed. Were those echoes I heard of the Berg’s Violin Concerto and its inheritance from Bach? Barenboim led a performance of shattering intensity, a scream from above announcing the fourth number, ‘Im Labyrinth’, words from Nietzsche’s Dionysus-Dithyramben. A furious chase, ultimately to the death? In part, but an uneasy stillness and quest for recognition, both of which, as in Berg’s operas, proved as much instrumental and vocal, were equally important. Lyrical reminiscences of a German Romantic world from which a certain distance could yet be retained: could there have been a more in-keeping response to Heine, in the following ‘Traurig schau ich in die Höh’’? Wozzeck-like tread and post-Lulu harmonies continued to suggest a Bergian trail, which may or may not have been the true path through the labyrinth. For the final ‘Tötung des Minotaur’, Widmann, Aristidou, and indeed the ensemble as a whole suggested a revenge at first Ariadne’s, yet ultimately that of Dionysus. Yes, this was Nietzsche again. Blood-red sun above the stage brought visual as well as aural attention to trumpeters proclaiming in triumph glow of death against Ariadne’s white. We were all, however, in the labyrinth now; such is the power of music. Mahlerian explosion and death rattle lingered, even seduced. ‘Ich bin dein Labyrinth …’

Mark Berry