Switzerland Mussorgsky, Boris Godunov: Soloists, Chorus of the Zurich Opera, Philharmonia Zurich / Kirill Karabits (conductor), Zurich Opera, Zurich. 20.9.2020. (JR)

Switzerland Mussorgsky, Boris Godunov: Soloists, Chorus of the Zurich Opera, Philharmonia Zurich / Kirill Karabits (conductor), Zurich Opera, Zurich. 20.9.2020. (JR)

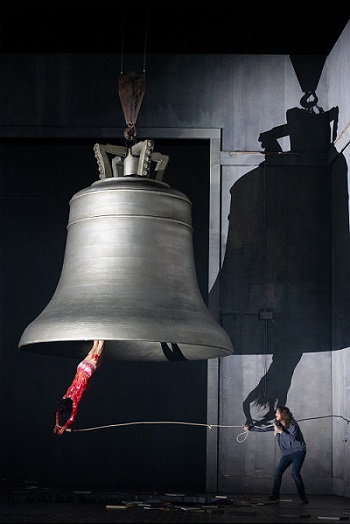

(c) Monika Rittershaus

Production:

Director – Barrie Kosky

Set – Rufus Didwiszus

Costumes – Klaus Bruns

Lighting – Franck Evin

Chorus – Ernst Raffelsberger

Dramaturgy –Kathrin Brunner

Cast included:

Boris Godunov – Michael Volle

Xenia – Lina Dambrauskaité

Fyodor – Soloist from the Tölzer Boys’ Choir

Nurse – Irène Friedli

Count Schuisky – John Daszak

Andrei Schtschelkalov – Konstantin Shushakov

Pimen – Brindley Sherratt

Grigoriy – Edgaras Montvidas

Marina Mnischek – Oksana Volkova

Rangoni – Johannes Martin Kränzle

Varlaam – Alexei Botnarciuc

Missail – Iain Milne

Hostess – Katia Ledoux

Fool – Spencer Lang

Police Officer – Valeriy Murga

Trite to say, the coronavirus is making life difficult for us all, but full marks to the team at Zurich Opera for opening the season with a grand opera, Boris Godunov. The opera house can seat 1,200 so with a Covid-19 restriction of 1,000, and taking into account the soloists and other staff, about three quarters of the seats could be sold. No social distancing was required or in place (you get a better class of coronavirus at the opera house); we all dutifully wore masks, of course. The management had the ingenious idea in order to increase audience numbers and to ensure their employees remained safe, by placing the conductor, orchestra and chorus in an external venue. They chose the orchestra’s cavernous rehearsal room, the size of a small concert hall, in a building less than half a mile from the opera house and had the sound transmitted (not compressed, using fibre optic cables) into the opera house.

Before each act started, we saw the conductor and orchestra on a large video screen (and they could hear our applause). I must admit I had my doubts as to sight and sound beforehand but have to say that I was highly impressed. At the beginning it did rather feel like I was listening to a recording, but a very high quality one. Only the bells at the beginning of the coronation scene were a trifle muffled. I reflected that, in Bayreuth, Wagner designed the orchestra pit so that the conductor and players were unseen, allowing the voices not to have to compete with the force of the sound from his players. Once the singing started, the orchestral accompaniment was less prominent and one concentrated primarily on the voices on stage. What was sadly missing, however, was the spectacle of the crowd scenes, the grand entrance of the Boyars and their rich costumes.

Barrie Kosky had, of course, to revise his original plans for the opera, with no chorus on stage. Boris could never have been transformed into a chamber opera with a reduced number of musicians; Mussorgsky’s scoring and the whole effect of the opera would have been decimated.

The production brings the action (set in the 1590s) almost bang up to date; only the shape of the computers and the costumes indicated we were in the 1970s. The elements of the plot are, of course, replicated in many a Shakespearean play (one only has to think of Macbeth), many a recent Novichok poisoning, and the political machinations in Belarus, so it translates well to the modern era.

The Fool became a central character in this Kosky production, on stage as a witness of all the events (even appearing as Widow Twankey in the Polish ballet). It was a triumphant night for young Spencer Lang.

The scenery was almost uniformly grey. So were, by and large, the costumes. The Fool sported a multi-coloured hoodie, Boris had a splendid robe for the ceremonial scenes, and was allowed a scruffy brown suit for the other suits. His lank wig made him look suitably bedraggled to reflect his tortured soul.

The opening scene took place in what was supposed to be, I believe, the Library of the Kremlin, with huge shelving units on wheels, full of dusty books and files. It also looked like the filing room at the KGB or Stasi. Replacing the opening chorus, some books were made to open and close to the rhythm of the singing, an unnecessary gimmick that just made for giggles. Boris is not by any stretch of the imagination a comic opera, even though the mood is lightened by the two drunken monks. The Polish scene introduced some colour to the set, in the shape of a golden wall; Marina sported a golden gown, suitably low cut to attract Grigory. The final scenes centred around a huge grey bell, which was made to ascend and descend at suitable moments, to crush its dying victims. Pimen and Boris jumped into the well below the bell at their moments of demise. Kosky’s production was ingenious at all times, often clever but sometimes irksome. The final scene depicted the revolution not with a glorious ride into Moscow but with a series of bloodied bodies. Varlaam and Mikhail, the wandering monks, appeared with heads bloodied to sing their final farewell, before presumably being tortured and killed as Christians. A lone, swinging, bloodied youth was suspended from the bell – we puzzled as to who this might be.

I must admit I had qualms about hearing a baritone in the role of Boris. Barrie Kosky in the programme interview reminds us that in fact the original singer, Iwan Melnikow, was not a bass but a baritone. I had no fear that Michael Volle would not sound magnificent and have the necessary acting skills; he succeeded splendidly at all levels. It was a veritable tour de force. The part’s tessitura lies high, and deep basses often have to strain to reach some of the top notes. The only downside is that the Tsar lacks a certain dark gravitas.

Although we missed the visual impact of the downtrodden frozen hordes of the populace of Moscow (the wardrobe department was relieved of work and the opera house of expense), we were compensated by two scenes often omitted from performances – the Polish Scene and the final Revolution Scene, supposed to be in the wood near Kromy. Both are, I think, necessary to fully understand the plot and both have some beautiful and stirring music to savour.

The voices were splendid throughout. I have already mentioned Michael Volle, for whom this role will surely become a mainstay of his repertoire. He will learn to make some of the sounds more Russian. The same criticism applies to John Daszak, but otherwise he made for a strongly voiced, creepy, supercilious Shuisky. For the real Russian flavour, one marvelled at the tone and force of baritone Konstantin Shushakov, perfect in the minor role of Schtschelkalov, Secretary of the Duma.

Brindley Sherratt as Pimen was first-rate, chronicling by hand rather than on the laptop on his desk. Lithuanian tenor Edgaras Montvidas was a discovery, and made a strongly voiced and impressive Pretender. Johannes Martin Kränzle as Rangoni particularly relished the acting side of his role, decadently licking his lips on some cream cakes at the end as he contemplated religious victory in Moscow. All the other roles were taken at the highest possible levels; it was palpable how everyone was pleased to be back on stage, at last.

The orchestra sounded polished throughout, Kirill Karabits taking quite a slow reading of parts of the score, which added a certain nobility. He must have dashed from the final page of the score (perhaps his assistant did the honours) to appear, on time, for the curtain call. Instead of pointing to the pit to applaud his players, he pointed to the sound engineer at the back of the stalls, who had worked hard throughout the evening.

Zurich Opera must, just now, be the envy of the operatic world – who else is courageous enough (and allowed) to put on grand opera to a virtually full opera house?

Those who would like to watch the performance online can catch it on Saturday, September 26th, courtesy of ‘oper für alle – digital’ (click here).

John Rhodes